Why we still have Austen-mania

Jane Austen’s work forms an enduring strand of our cultural DNA. Matthew Dennison explains how she revolutionised novel-writing and why she’s still much loved 200 years on.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

That young lady had a talent for describing the involvements and feelings and characters of ordinary life, which is to me the most wonderful I ever met with,’ wrote Sir Walter Scott in his diary in March 1826, after reading Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice for the third time.

Unreservedly, he celebrated Austen’s ‘exquisite touch’ and her ability to make ‘commonplace things and characters interesting from the truth of the description and the sentiment’. By contrast, Thomas Carlyle dismissed her six novels as ‘dishwashings’ and ‘dismal trash’.

Happily—and with good reason—posterity has mostly preferred Scott’s verdict on Britain’s best-loved female novelist, who died 200 years ago, at the age of 41. Austen defined her approach to fiction as working on a ‘little bit (two Inches wide) of Ivory… with so fine a brush, as produces little effect after much labour’, typically stories centred on ‘three or four families in a Country Village’.

"Like the works of Shakespeare and Dickens, Austen’s writing forms a strand of our cultural DNA"

She did not intend this deprecating self-estimation to be taken at face value. ‘I must keep to my own style & go on in my own Way,’ she wrote with dogged conviction the year before her death. She was fully aware of the effect of her labour and the validity of her approach, which contrasted with the more histrionic effusions of her contemporaries, notably the Gothic novels of Ann Radcliffe, which she satirised in Northanger Abbey.

Austen achieved cult status tardily, a late-Victorian phenomenon rebooted more recently in the Austen-mania that followed Andrew Davies’s 1995 adaptation of Pride and Prejudice for the BBC, with a host of other 1990s and 2000s film and television adaptations and spin-offs.

However, despite modest sales in her own lifetime, the author revolutionised novel writing. Her adoption of what critics cumbrously label ‘free indirect discourse’, a merging of third-person and first-person narratives, enabled her realistically to express her characters’ voices and thoughts.

Her fiction presented female protagonists apparently glimpsed from the inside. With a light, often sardonic touch, she captured unchanging truths, like the moment in Emma when Harriet Smith, seeing Mr Elton’s trunk being loaded into a cart for Bath, realises that her would-be husband is departing ‘and every thing in this world, except that trunk and the direction, was consequently a blank’. She wrote novels about men and women, which, for two centuries, have engaged readers of both sexes.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Today’s ‘Jane Austen’ is a much-mythologised figure. In his memoir of his aunt published in 1870, James Edward Austen-Leigh wrote: ‘We did not think of her as being clever, still less as being famous; but we valued her as one always kind, sympathising, and amusing.’ Despite her work’s prickly wit, this saccharine version of the novelist continues to enjoy wide currency.

In Winchester Cathedral, flower arrangements dedicated to Austen, in her role of distinguished local author, have typically been dominated by sugar-pink roses. Her wide-ranging appeal—the existence of this heritage-industry, tea-towel and Sunday-night TV-adaptation Austen alongside less cloying versions—is itself a facet of her genius, proof of the enduring vividness of her fictional world and the insight and pertinacity of her observations on that world.

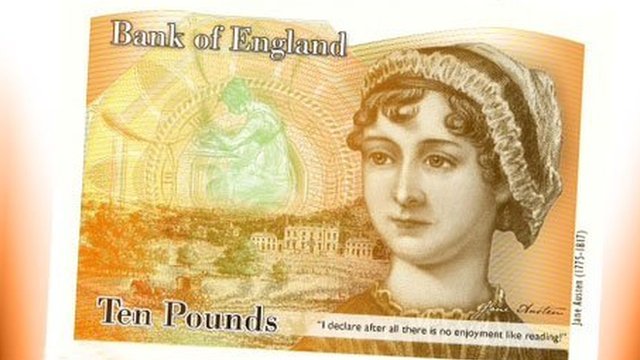

Readers and non-readers alike cherish their own Austen. As one critic indicated recently, she is the only British novelist identifiable simply from her Christian name. Her appearance later this year on a new £10 note will consolidate her position as the only female British writer instantly recognisable from her portrait.

Austen’s genius lies in the liveliness and certainty of her characterisation and her extraordinary mastery of irony, which colours, undercuts and elevates each observation of every novel. To read these books absorbedly is to see the world afresh and yet within a framework that seems both inevitable and inarguable.

American literary critic Harold Bloom claimed that ‘Austen invented us’. In Britain her view of humanity and society has indelibly shaped our vision of ourselves. Like the works of Shakespeare and Dickens, Austen’s writing forms a strand of our cultural DNA—no mean achievement, given the emotional costiveness and aversion to self-absorption typical of our island race.

A reviewer of Anna Maria Bennett’s Anna; or, Memoirs of a Welch Heiress: Interspersed with Anecdotes of a Nabob (1785) suggested ‘the incidents are scarcely within the verge of probability; and the language is generally incorrect’.

Few critics today would level either criticism at Austen. Her novels retain the ability to consume their readers imaginatively. She was an expert storyteller and an adroit plotter. These novels are read on beaches and buses as well as in the classroom.

This year’s anniversary of Austen’s death offers a nudge to revisit her slender oeuvre. The pellucid prose, so carefully and expertly modulated, reminds us of the glories of our language. Her novels show us the wonders of human interaction: its agonies and, ultimately, its ecstasies.

Where to celebrate the 200th anniversary of Jane Austen

2017 marks the 200th anniversary of Jane Austen's death. Here are exhibitions and events that mark the occasion.

Which Bennet sister are you?

The Bennet sisters in Pride and Prejudice are some of Jane Austen's most memorable creations - take our quiz and

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by His Majesty The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.