‘One remembers not to give the Queen a thump of joyful friendliness’: Remembering Norman Parkinson — revolutionary fashion photographer and Cecil Beaton’s only homegrown rival

Cecil Beaton might be the toast of London right now, with a new exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery, but contemporary Norman Parkinson was always hot on his heels.

Norman Parkinson (1913-90) told an interviewer, late in life and perhaps a little wistfully, that he might liked to have been a racing driver. In his youth he had been the proud owner of an Italian ‘Mille Miglia’ OM tourer, a novelty on British roads. He was also something of a ‘debs delight’ and, according to his memoir, England’s junior waltz champion. Some of his earliest pictures were of motor cars shot on 10-second exposures, their blurred forms like fleeing spectres of metal and rubber. A 1936 portrait of his father in driving helmet and goggles is titled ‘The Age of Speed’.

It was during the turbo-charged Modernist 1930s that Parkinson’s pictures came of age. In time he would become one of Britain’s best-known fashion and portrait photographers with a career at Vogue that took him from 1941, with a break in the 1960s, to around 1978 — when they fell out spectacularly — but he was still shooting fashion well into his seventies. When he died in 1990, it was on a fashion assignment in Malaysia for Town & Country.

For many years, his only serious homegrown rival was Cecil Beaton, and at Vogue they were on cordial terms. This changed when Parkinson achieved success as a royal photographer, a field that Beaton had diligently fenced off for himself.

'Perhaps to compensate for his sheer unmistakableness, Parkinson created an outer shell of ostentatious eccentricity'

In truth, London-born Parkinson did not have much of a chance at anything else. It was at Westminster (where his only distinction, he said, was being the tallest boy in the school) that an invitation arrived suggesting a pupil take up an apprenticeship at the photographers Speaight and Sons. Everyone was relieved when young Ronald Smith (Parkinson’s real name) put up his hand, the more so when he secured it.

Speaight was a fashionable court photographer now on the slide, there being fierce competition in London’s West End. He spent two years in the studio with Speaight and, in 1934, he opened aged 21 and with a change of name, the Norman Parkinson Studio at 1, Dover Street, almost opposite the Ritz hotel, as fashionable an address as you could get. There he specialised in debutantes, ermine-clad peeresses and celebrity pictures: Noël Coward, the Sitwells, Vivien Leigh, a young John F. Kennedy and an even younger Petula Clarke.

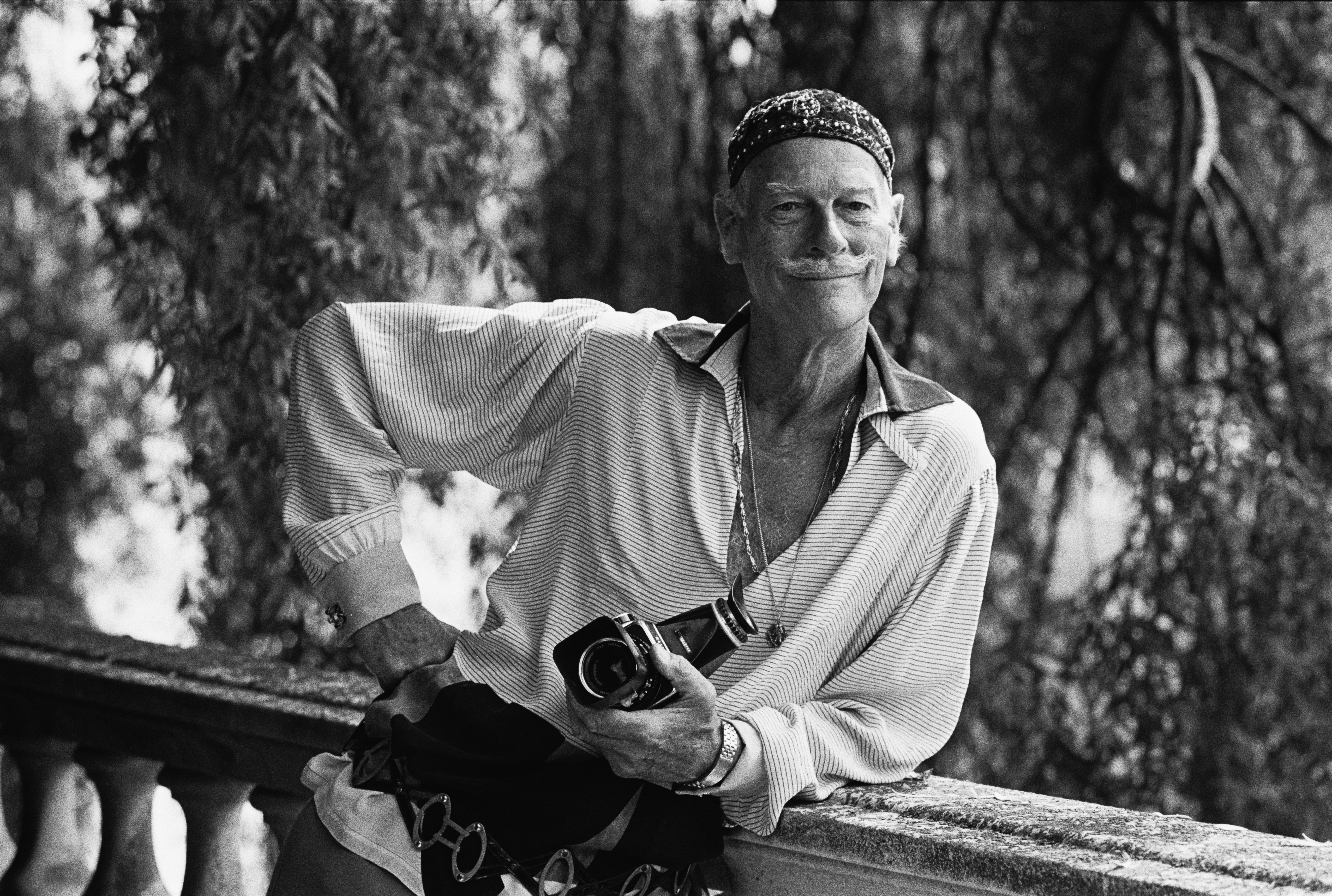

At 6ft 6in tall with a rakish moustache, smartly dressed and ram-rod-backed like the guardsman people assumed he was, Parkinson created an impression. Yet Beaton found him ‘disarmingly unsure of himself’ and, perhaps to compensate for his sheer unmistakableness, Parkinson created an outer shell of ostentatious eccentricity. Throughout his life, he was conspicuous by a strong sense of fashion, which sometimes, like his photographs, teetered on the knife-edge of good taste.

He was very proud of his country roots; his paternal forebears were Wiltshire market gardeners, who had also manned the smithy at Tetbury, while his half-Italian mother was descended from a line of opera singers. The mixture of rustic and urban genes he inherited ‘makes me feel equally at home waiting patiently among the brambles over a badger’s earth, or among the marble pillars and gilded ceilings of an Italian palazzo.’ He formed as deep an attachment to rural life as any city-born person might, and being rooted to the badger’s earth acted as a source of strength and comfort, as well as a counterpoint to the vagaries of the fashion world.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Model Chandrika Angadi photographed with two dogs wearing Saint Laurent, published in 'Vogue', in July, 1970.

By 1941 when his first picture was published in Vogue — a utilitarian cycling outfit — he had closed his Mayfair studio. Much of his early work was lost to the Blitz, as was part of Westminster school and all of Speaight and Sons. The cycling ensemble was taken against a rural backdrop and Vogue had little choice in the setting. Parkinson’s wartime fashion pictures would be firmly fixed to the countryside, because he had acquired a 100-acre farm at Bushley in the Malvern Hills.

Combining agriculture and photography at the nation’s darkest hour, Parkinson was able to tap into that spirit of neo-romanticism that underscored the virtues of the countryside, its simpler ways of life and traditions. In five years, without having to set foot further than Tewksbury or Gloucester, Parkinson had stamped his mark on the magazine. In 1947 he returned to the studio and began for Vogue a series of dramatically lit fashion pictures. His photographs admitted not only women who might milk a cow with assurance, but also those of rarefied hauteur, such as Barbara Goalen who epitomised the mid-century couture. The fashion industry had been revitalised by Christian Dior’s New Look collections of 1947 and 1948, which, together with a greater allocation of colour pages, rejuvenated Vogue in the post-war years. With his wife, the model Wenda Rogerson, he would make some of Vogue’s — and post-war fashion photography’s — most readily identifiable images: she draped herself over the bonnet of a Rolls-Royce Silver Ghost, she leant over the five-bar gate of a muddy Gloucestershire field, and in South Africa — it was the beginning of the age of jet travel — she rode a runaway ostrich. ‘More profile, Wenda, more profile!’ admonished her husband as she disappeared from view. She offered up to his camera, as he put it, ‘a quiet beauty… frozen, permanent, it does not age’. And he was right. We see them time and again.

Parkinson also reacquainted himself with London life, having swapped the farm for a Regency house in Twickenham. He had eclipsed his colleagues at Vogue to become its leading photographer, finding no serious rival now in Beaton, whose war work had exhausted him, leaving him with little appetite for fashion.

Throughout the 1950s he made frequent visits to American Vogue which recognised that Parkinson’s esprit — even if determinedly English and preferably in black-and-white — could be translated into colour on the streets of New York. In the Parkinson physiognomy the rustic yielded further to the urban.

As the 1960s turned to the 1970s, he found a new role as a royal photographer, much to the chagrin of Beaton. Where Beaton could be a little formal — after all he had photographed Elizabeth II’s Coronation — Parkinson’s pictures were less so, relaxed even. Princess Anne riding High Jinks in Windsor Great Park, Princess Margaret’s children clambering over their father, the Earl of Snowdon, in the grounds of Kensington Palace. He summed up his approach: ‘The royal family is just a family. Of course, one maintains one’s respectful distance — one remembers not to give the Queen a thump of joyful friendliness or bite the Duke of Edinburgh in the calf …’

When I met Parkinson in Vogue House in the late 1980s, where he was still welcome despite an unresolved dispute, age had not diminished him — he still stood straight as a guardsman, he still had the moustache — nor had it tamed his fashion sense. It was a bravura display. A long-jacketed safari suit in cotton seersucker, beneath it a collarless shirt in bold stripes, buttoned up to the top, all rounded off with a beret. He looked at once both old-fashioned and defiantly modern. Not long afterwards he would set out on that final assignment for Town & Country.

Professional to the end, he completed several pictures before being taken ill, with some published posthumously. One of them featured a bare-breasted Deborah Harris perched on a rocky outcrop in a custom-made mermaid-tail by over-the-top American designer Bob Mackie, accessorised with an oversized feathered headdress while pouring water from a conch shell and attended by several obliging turtles. Now that really was a bravura display. Flashy and camp it was entirely right as the curtain rang down on the Reaganite 1980s. And nothing summed up an era quite like Parkinson’s pictures. When his 40th birthday portrait of Elizabeth Taylor, royalty of a kind, appeared in Life magazine in 1972, eyebrows were raised as the star’s specially-designed wig appeared to match her favourite Shih Zhu’s own hairstyle.

A post shared by Norman Parkinson (@norman_parkinson)

A photo posted by on

Swaying further on the tightrope of taste, came the now infamous Royal Blue Trinity, a triple portrait marking the 80th birthday of the Queen Mother. Parkinson wheedled, somehow, Elizabeth II, her mother and her sister into identical bright blue satin capes specially run up for the occasion by Hardy Amies: ‘I feel it may make a timeless, fashion-free picture which will ensure its place of importance in the future,’ he announced, a little dangerously. It was greeted instead by near universal scorn, the three royal personages resembling nothing so much as a kitschy supper club sister (and mother) act, but it did nothing to harm his royal patronage.

But that was Parkinson all over. He never did what was expected of him, he never believed that good taste was necessarily a good thing and he was wholly and always his own person.

For many years he and Wenda lived in Tobago in the West Indies. His long absences had made his feelings for the English countryside rose-tinted. Shortly before he died, he returned to the Thames valley where as a child he had been evacuated from the Zeppelin threat over London. The intrusion of motorways, chain-link fences and industrial estates made him, he said, ‘almost sleeplessly apprehensive about this corner of England I had come to love’ if now from a distance. At Henley, on the stretch of river he had once rowed upon for Westminster, he was equally downcast: ‘even this sacred mile-and-a-half is now no longer safe…’

He hoped, he said, to be remembered as ‘a tiny Gainsborough’ and perhaps in his way if any photographer can, Norman Parkinson is. But no doubt about it — what a flamboyant racing driver young Ronald Smith would have made.

Robin is a photographic historian and writer on photography. He has curated major exhibitions at the National Portrait Gallery, the Victoria & Albert Museum and the Yale Centre for British Art, New Haven. Formerly picture editor of British Vogue, he is currently a contributing editor with the magazine.