Country house libraries

Private libraries continue to be created despite the inexorable advance of the internet. Jeremy Musson visits three recent examples

The library as a room, as well as a collection of books, has a long and vibrant history in the English house. Private libraries were known in the later-medieval and early-modern world as rooms containing manuscript collections. They were clearly considered places of private pleasure and might be furnished with particular splendour. In the early 16th century, for example, the 5th Earl of Northumberland had a library in one of the towers of his quadrangular castle at Wressle, East Yorkshire. It was fitted with bookshelves surmounted with lecterns that could be pulled down on rails to a convenient height for the reader and was known affectionately as ‘Paradise'.

The library remained an indispensable room in the houses of the educated and wealthy. Great designers responded to the requirements of libraries with rooms in which the ordering and display of books became part of the essential aesthetic impact of the space: William Kent's libraries at Holkham and Houghton and Robert Adam's libraries at Syon, Harewood, Nostell Priory and Kenwood all express the civilised cultural ambitions of sophisticated Georgians. Contemporary visitors might well judge the owner of a house by the quality of the books in their collection as much as by the art on their walls.

Those who used libraries regularly could show a passionate interest in the appearance and organisation of these rooms. Think of Samuel Pepys's books and his original bookcases, now preserved at Magdalene College, Cambridge, or Horace Walpole's Gothic library at Strawberry Hill. By the early 1800s, the library in grander houses had often become the family sitting room. Whatever domestic elegancies they might possess, they would always hold well-ordered and extensive book collections, arranged into themes: classical literature and poetry, history, politics and topography, as well as volumes of architectural engravings (many country houses had their own librarians).

Mark Purcell, libraries curator for the National Trust, observes: ‘Libraries were being put together in remote country houses by gentlemen amateur scholars in an age when the principal libraries might otherwise be hundreds of miles away.' Despite the growing importance of the internet, new libraries are being made all the time. Three recent examples, all made within private houses for writers and academics, illustrate some of the key themes in the story of the survival of the personal library room into the 21st century.

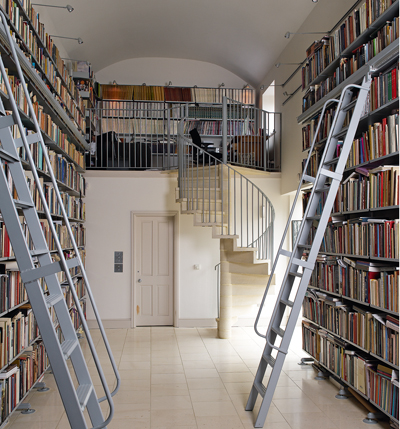

The library created within an old stable range for arts journalist Susan Moore and art historian David Ekserdjian at their old rectory home. The shelving system is supplied by Vitsoe.

One of these is a bold, double-height room-with vast walls of books- created within a former stable. The room was made for a married couple, both writers: Arts journalist Susan Moore and art historian and academic Prof David Ekserdjian. Their home is an old rectory of medieval origins, so the library, as a contribution in modern times, was deliberately designed to be contemporary and functional in character.

Thousands of books line the walls to a height of 14ft, the higher shelves approached by moveable ladders. Susan Moore, an art-market correspondent for the Financial Times and associate editor of Apollo, has a study/office with a writing desk on a mezzanine level and a window looking over the garden. ‘We have all the reference books at this level, dictionaries and back copies of The Burlington Magazine and Apollo-it is wonderful having everything at our fingertips. In our previous house in London, our books were spread over several floors.'

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The design of the library was developed with a young architect, Vanessa Pace of Wythe Holland Partnership. ‘The original stable was stone and brick, but we were told we needed cavity walls to turn it into a library, so a state-of-the-art design evolved. Vanessa went to enormous lengths to source the elements we needed, including the lights, bespoke ladders and railings.'

A new barrel-vaulted ceiling was created, which gives the room an echo of a quattrocento Italian chapel. The shelving system was supplied by Vitsoe and is from an original design by 1960s German architect Dieter Rams -indeed, it is a recognised design classic and displayed in MoMA in New York. The steps are fixed by a rail, but move along the shelves as required. Prof Ekserdjian is the author of major monographs on Parmigianino and Correggio and the co-curator of the 2012 Royal Academy exhibition ‘Bronze'. He explains their shared classification system: ‘One side is monographs arranged alphabetically, by artist, and the facing wall is museum and gallery catalogues, arranged by subject: painting, drawing, sculpture, prints. The end wall, opposite Susan's office, is for more general works on the history of art. This is very much a book depository and not a sitting room; we don't have sofas and chairs in here.' Susan adds: ‘We do use the internet, but in our field, the image is all-important and there is no doubt that books still offer one of the best means of looking at and comparing images.'

Another transformation of the interior of a former agricultural building into a writer's library is found in the East Anglian home of garden designer and author George Carter, who created the Garden of Surprises at Burghley and has worked on the new gardens at the Royal Hospital, Chelsea, London SW3. This is a comfortable, mellowflavoured room, created on a spacious mezzanine level in a vast 1830s barn, the greater part of which had been already been converted into a single large volume for entertaining.

Mr Carter, who designed the new space himself, observes: ‘I had to create a library rather urgently because it had become impossible to get into any upstairs room of my house-they were all overflowing with books. In essence, I needed a room where I could gather my architectural and gardening books and also use it as a working room, for research, reading, writing and design work.

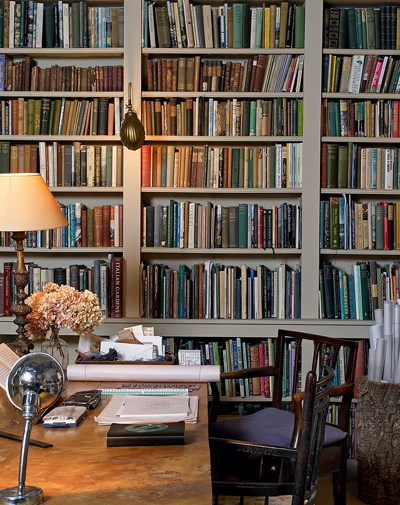

Author and garden designer George Carter created and designed this mellow study-cumlibrary within an 1830s barn at his home in Norfolk

So I decided to carve this study-library room out of the old barn. I am working on another room in another building, having recently acquired a complete run of bound volumes of Country Life, which needs to be suitably housed.' Mr Carter has divided up his bookshelves with simple pilasters, and the shell lights that illuminate the spines of the books were ‘inspired by the library of a friend, Shirley Cargill, who then lived at Elsing Hall. The best libraries are often favourite sitting rooms at the same time. I do occasionally use this room for drinks before giving a dinner party, but it is, really, a working room. It contains my drawing table where I do my design work. It is made up of a large piece of elm board, from a former coffin maker, and it stands on a pair of modern trestles modelled on the type you see in medieval illuminated manuscripts.'

Various chests contain the rolled-up plans of his garden designs. One inspiration for Mr Carter's comfortable, but eclectic library was Clough Williams- Ellis, ‘especially the way he put different things together in a single space'.

One of the finest of the new Classical library rooms was designed in 2008 by architect John Simpson, for architectural historian David Watkin, Fellow Emeritus of Peterhouse, Cambridge, and Emeritus Professor of the History of Architecture. He is author of many works on Classical architecture, including books on C. P. Cockerell, Thomas Hope and John Soane.

Fittingly, Prof Watkin's new library has strong echoes of Soane's designs for libraries and he especially sees a connection with that at Shotesham Park, Norfolk, of 1785-93, and the one at Aynhoe Park, Oxfordshire, of about 1800. Prof Watkin has known and championed Mr Simpson's work for 20 years-it includes projects at Gonville & Caius, Cambridge, and The Queen's Gallery at Buckingham Palace.

An ingenious play of light and shadow complements a new library by John Simpson for architectural historian David Watkin, whose huge collection comprises some 6,000 books with underfloor heating and a limestone floor.

For his library, Prof Watkin wanted to create a comfortable and elegant room that could hold his collection of architectural books, previously in his rooms in Cambridge, which includes an extensive selection that he inherited from his friend, Monsignor Alfred Gilbey-some 6,000 books altogether. Prof Watkin also wanted a room for music and conversation (a number of recitals have already been held there). Mr Simpson's bookcases and plaster ceiling had to work within a room of a somewhat complicated history, with some medieval walls. The house itself is largely Georgian in character and the library room had been fitted out in Palladian style in 1740-44, but its interior was sold to a museum in the USA in 1931. Now, the library has a sense of unity, with the bookcases running around three walls at a certain height, which accommodates a set of framed engravings by Piranesi.

Most importantly, the wall surfaces above the bookcases, windows, the chimneypiece and mirror are all articulated with a low, segmental arch, which enhances the play of light and shadow within the room. This is a key element in Soane's work, an architect admired by both Prof Watkin and Mr Simpson. Prof Watkin observes: ‘The arches over the windows are freestanding so that their silhouettes show up darkly against the light flooding in behind them. This pattern of light and shade is emphasised by the grooving of the undersides of the arches. It is this luminosity that Gandy, Soane's pupil, caught so well in his atmospheric watercolour of 1803, which shows the library Soane designed for Cricket Lodge in Somerset.'

These interiors illustrate the range of new libraries being created today, but they all share a sense of the survival of the printed book in the modern world as a source of knowledge, inspiration and pleasure.

* Follow Country Life magazine on Twitter

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by His Majesty The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.