Glyndebourne House: The 'entrancing' home with an organ so enormous that 'it brought plaster crashing down from the ceiling when it was first played'

Easily overlooked beside the opera that has made its name world famous, Glyndebourne House in East Sussex — home of Gus Christie and Danielle de Niese — bears the architectural stamp of a remarkable 1930s revival, as Clive Aslet explains. Photographs by Paul Highnam for Country Life.

Glyndebourne is famous around the world as an opera house, with a country house at its heart. Today, guests who carry hampers to lake or ha-ha cannot but feel the charm of this convivial domestic setting, although the influence of it dims when they enter the auditorium itself — so sophisticated that it cannot simply be seen as an appurtenance to a family home. Yet that home continues to exist, playing a vital role as much in the life of the present generation of Christies as in that of the opera festival. Little altered since the days of John Christie, who built the first opera house in the 1930s, it stands as a living testament to his unstoppable dynamism, as well as his vision of what opera could be in this country.

Fig 1: The main front at Glyndebourne was built by Ewan Christie in the 1880s and remodelled by Edmond Warre, who imposed symmetry on it.

Glyndebourne has existed since at least the 16th century, to judge from fragments of chalk wall and early panelling that can be seen in its fabric. At one point, it was rented to the A’Wood family, from whom it acquired the unpromising early name of Woods Tenement in the Hole. Glyndebourne, as it has been known since the early 17th century, is a more generous tribute to the setting beneath the Downs, a ‘glind’ being a valley and ‘bourne’ a stream. In the 19th century, the property came, by marriage, into the hands of the Christie family, whose fortune had been established by Daniel Christie, originally Christin, a Swiss major in the army of the East India Company.

In the 1880s, William Christie, Daniel’s grandson, had the house comprehensively Victorianised by Ewan Christian (Fig 1). William’s son, Augustus, was mentally unstable, which cast a dark shadow over the childhood of his own son, John. At the end of his life, Augustus wrote a will that attempted to leave his estates, which included Tapeley in Devon, away from his immediate family; this was overturned by his widow, Lady Rosamund, in court. During the proceedings, John spoke of his father’s having been ‘demonstrably affectionate’ on visits before his death — on one occasion, he shook hands, on another he raised his hat.

"Under bombardment in the First World War, he would behave with impeccable sang froid, reading aloud from a copy of The Faerie Queene, produced from his pocket, to cheer up those who could hear him"

The misery of his unpredictable home life, oscillating between his father’s fits of violence and his mother’s smothering love, made Eton a refuge of normality. Christie did not excel, but, following the lead of the towering headmaster, Edmond Warre, famed for his rowing, he developed a zest for sport — even after a riding accident left him with a permanent limp and a rackets ball later blinded him in one eye. (He eventually replaced the eye with a glass one that could be removed for dramatic effect.) Although intended for the army, he did not stay the course at Woolwich, which he entered in 1900, and went up to Cambridge instead. ‘Mind you come down well dressed,’ he told his mother when she was about to set out to visit the rooms he had decorated.

Fig 2: John Christie, who founded the opera festival, employed Warre, who was the son of the headmaster at Christie’s much-loved alma mater, Eton College, to add a new hall.

Albeit not above pranks — friends once hoaxed the Mayor of Cambridge by appearing as the supposed Sultan of Zanzibar and his suite — Christie applied himself to the study of physics, chemistry and mineralogy. He also fell heavily for Wagner and motoring, combining the two passions in a motor trip to Bayreuth in Germany. According to his incomparable biographer, Wilfrid Blunt, his parents strongly encouraged him to find some gainful employment when he went down — although, financially, he hardly needed a job. Consequently, he returned to the Elysium of his youth, Eton, where he taught the relatively new subject of science.

As a sportsman, Christie was a hit with the boys and, being rich, he could buy expensive equipment that he gave to the school; his liquid air pump may not have produced liquid air, but it was useful for pumping up the tyres of his car. He was not good at explaining himself and, therefore, a poor teacher, but, according to his scholarly colleague A. S. F. Gow, pupils enjoyed the arrival of his ‘Jeeves-like butler, Childs, to announce that Capt Christie had overslept, but he might be expected shortly’. Christie owed his rank to the First World War, during which he managed to enlist, despite the limp and lack of an eye, by tricking the doctor who was examining him. Under bombardment, he would behave with impeccable sang froid, reading aloud from a copy of The Faerie Queene, produced from his pocket, to cheer up those who could hear him. He did everything he could to avoid the fuss of being awarded a medal, but could not escape the MC.

Fig 3: The reverberation from the organ was so great it hasn’t been played since the 1950s, but, now, the room is ideal for entertaining the operas’ conductors, directors and cast.

‘The world was very good, in the opening years of the century, to those who were young and eager and affluent,’ observed Blunt. War may have shattered this idyll, but Christie sought to reclaim its spirit at Glyndebourne, acquired through a property swap with his father. He had always preferred this estate over other options in the family portfolio and set about updating it with a will. As early as 1916, with the war still raging and building work stopped, he had written to his mother: ‘I should like to see Glyndebourne put into order within the next two or three years.’ He found its present state ‘quite unpleasing’ and announced that a railway wagon of furniture would soon be arriving from Eton. All the furniture and pictures bought by his grandfather would go.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

For an architect, Christie turned, typically, to an Eton connection, Edmond Warre — not the headmaster, but his son, otherwise known as Bear. Born in 1877, Warre is known to have practised as a restorer of churches in the Edwardian decade, living in Chelsea. Like Christie, he served as an officer during the First World War. He is recorded as having designed a church in Enfield, Hertfordshire; he also altered Ringmer church in East Sussex at Christie’s expense. Glyndebourne was his chef d’oeuvre. Here, he transformed the main front, demolishing a tower and imposing symmetry. Internally, he created a large, ground-floor sitting room with a bay window (Fig 8), off which the main stair and study opened.

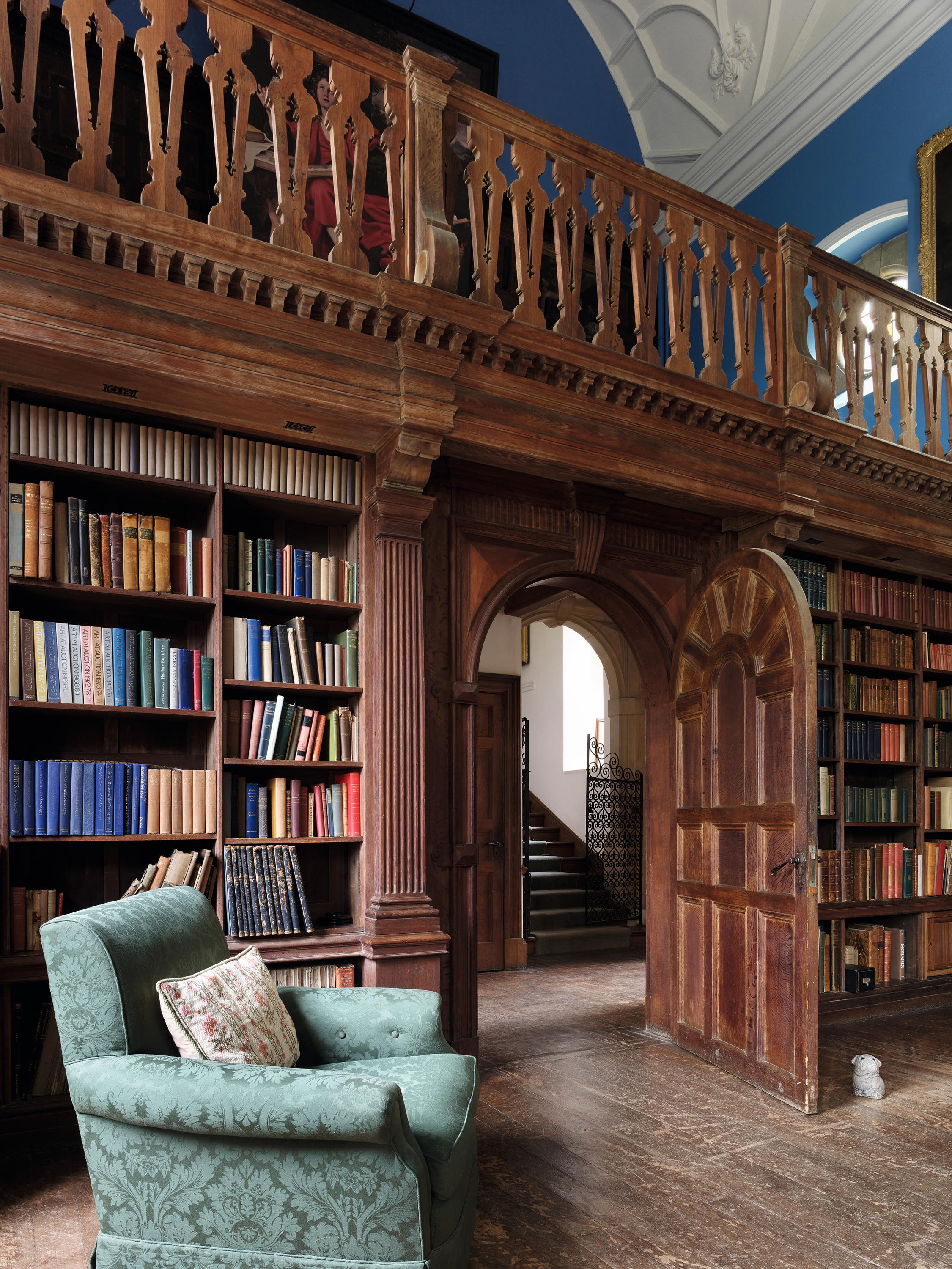

Fig 4: The library at Glyndebourne.

As yet, with no Mrs Christie to grace the house, its owner stood in need of a companion with whom he could talk music. Fortunately, one was available in an older friend, the Precentor of Eton, Dr Charles Harford Lloyd. An organist and composer, Lloyd had accompanied Christie on the trip to Bayreuth. Now aged 69, he was looking for a place to retire. The vicinity of Glyndebourne was rejected because it had no good organ for him to play; Christie countered by building one.

To house it, Warre created a spacious hall (Fig 2) that transformed the south front of Christian’s building, demolishing a fives court to create the necessary space for it. With bay windows overlooking the garden, this barrel-vaulted room, defying the growing preference for compactness that came in after the First World War, has proved to be eminently practical for Glyndebourne’s use in the 21st century: it is an ideal size for the cast parties and receptions that are held regularly during the Festival. The organ occupies the whole of an end wall (Fig 3).

Fig 5: Through this stairway arch you can still see the original, ancient timber-framing.

It might seem that the Glyndebourne organ is a late flowering of the turn-of-the 20th-century craze for organs among plutocrats and grandees, such as the Duke of Marlborough at Blenheim in Oxfordshire, Andrew Carnegie at Skibo Castle in Sutherland and Sir George Bulloch at Kinloch Castle on the island of Rhum. Player organs, heavily advertised in Country Life and elsewhere by the Aeolian Company of New York, became one of the status symbols of the age. Only the very rich could afford them because, as at Glyndebourne, major building works were needed to install the biggest of the range. Operated by a pianola-like roll, as well as the conventional keyboards, they provided music of all kinds, sometimes accompanied by side drums and cymbals, to an age that liked dancing, but still awaited the gramophone.

As designed by Lloyd, the Glyndebourne instrument would have been a more serious affair — but, sadly, he did not live to see it completed, having died on October 16, 1919, his 70th birthday. By the time it was ready a year or so later, the organ had undergone numerous tweaks and refinements, including the addition of enormous, slowly reverberating pipes that brought plaster crashing down from the ceiling when they were first played.

Fig 6: Although the opera festival is now a major enterprise, Glyndebourne house itself retains the charm of a traditional English country house, little altered since the 1930s.

Christie was entranced by this demonstration of power, but Donald Beard of Hill, Norman and Beard, the company that had built the organ, found the project exasperating, having been ‘wrong and ill-advised from the very start’. Christie had no such qualms. Countering an accusation of extravagance from Lady Rosamund, he cited the pleasure it would provide him, the money that could be raised for good causes and the savings he made by not running a shoot. Alas, in the 1950s, alterations to the opera house reduced the organ to a voiceless shell. His grandson Gus Christie, now executive chairman, wonders whether one day it might not be restored.

In 1923, John Christie bought Hill, Norman and Beard; he intended to obtain a monopoly on organ-building in the UK and had some success when cinema organs became big. This followed a pattern of investment in undertakings associated with the house. At the time of the alterations, carriage was provided by the Glyndebourne Motor Works, as the estate yard grew into a major contractor, renamed the Ringmer Building Works (RBW). Later, the RBW would prove useful for constructing sets. There is no doubt that Christie was impulsive, but he was not always wrong. ‘Can you grow grapes?’ he asked Frank Harvey, when grilling him for the post of head gardener in 1924. ‘Can you grow peas and celery?’ Replying ‘yes’ to these questions, he was engaged immediately. As developed by Harvey, the gardens literally blossomed.

Fig 7: Dramatic fabrics add colour to the Arts-and-Crafts interiors.

In time, the Organ Room made an unexpected proof of its worth by introducing Christie to his future wife, Audrey Mildmay. A young soprano, she sang Mozart there and he was immediately smitten. Audrey herself was more cautious. ‘You are such a darling, John, that I don’t want you to fall in love with me,’ she replied after receiving ‘one of the very nicest letters I have ever had in my life’.

That was on January 6, 1930; that very June, they were married. This can have come as little surprise to the company, in front of whom Audrey had opened a box sent to the stage door that she had assumed would contain flowers, but was instead packed with furs against the cold (The legacy, April 23).

Out of that love story, the Glyndebourne Festival was born. With unquenchable idealism, the Christies began a campaign to elevate opera in England — then at a low ebb — to the highest international standards. Practical as ever, John maintained, in a letter to The Times, that this would create a demand for British artists, making them a credible export.

Fig 8: The bay window looks out over the famous gardens loved by operagoers.

First, the Organ Room was extended, then an opera house for 300 was designed by Warre. Country Life made the best of the large fly tower when it visited shortly before the Second World War: the oak shingles that faced it would ‘yearly weather to a softer grey’. This was replaced by Michael Hopkins’s highly accomplished auditorium, leaving only the green room and its terrace, faced in handmade brick interspersed with clunch lumps, as evidence of the previous scheme.

With another opera singer, Danielle de Niese, as chatelaine, Glyndebourne continues to strive after Christie’s ideal, even the kitchen a product of the stage (Fig 9). The world-class conductors, directors, lighting designers and choreographers who stay for the Festival use rooms that seem to have changed little since John Christie’s time (Figs 4, 6 and 7). The service-corridor panelling is painted chocolate, the plumbing speaks of a more heroic age and Tudor timber-framing (Fig 5) and plaster is left exposed, evoking the inter-war aesthetic. The result is entrancing. No wonder excellence at every level is the result.

Visit www.glyndebourne.com

This article first appeared in Country Life's issue of May 14, 2025.

Fig 9: The kitchen, its units painted in the 1960s by a set designer as playing cards.