Richard Rogers: 'Talking Buildings' is a fitting testament to the elegance of utility

A new exhibition at Sir John Soane's museum dissects the seminal works of Richard Rogers, one of Britain's greatest architects.

The first building that I ever fell in love with was Lloyd’s of London. My dad worked there. He took me along for some work experience, and as we walked from Liverpool Street Station, I remember seeing the building for the first time and thinking: ‘Gosh that is very very ugly indeed’. I was not alone. When it was first built, in 1986, the radical design was not to everyone’s taste.

From the outside, Lloyd’s is something of a carbuncle. In the confines of the tradition of the City of London, it seems out of place; a writhing mass of tubes, glass, concrete and steel. It was only when inside that I began to understand it. Lloyd’s looks the way it does, because it is inside out. Within the walls, behind the tubes and vents and staircases, there is that most precious architectural commodity — space.

Lloyd’s is perhaps the defining building of Richard Rogers’s career (1933 – 2021), and the one that best executes his ideas on structure and form, as well as utility and functionality. It is one of eight buildings that underpin a new exhibition at Sir John Soane’s Museum, titled Richard Rogers: Talking buildings (until September 21).

Others include the Millennium Dome and Paris’s Pompidou Centre, as well as smaller residential buildings such as the Zip-Up House and The Rogers House. The exhibition, curated and designed by Rogers’s son Ab, creates an inspiring narrative that lends further weight to the argument that Rogers is to be considered one of Britain’s greatest ever architects, and this is the first retrospective of his work since his death in 2021.

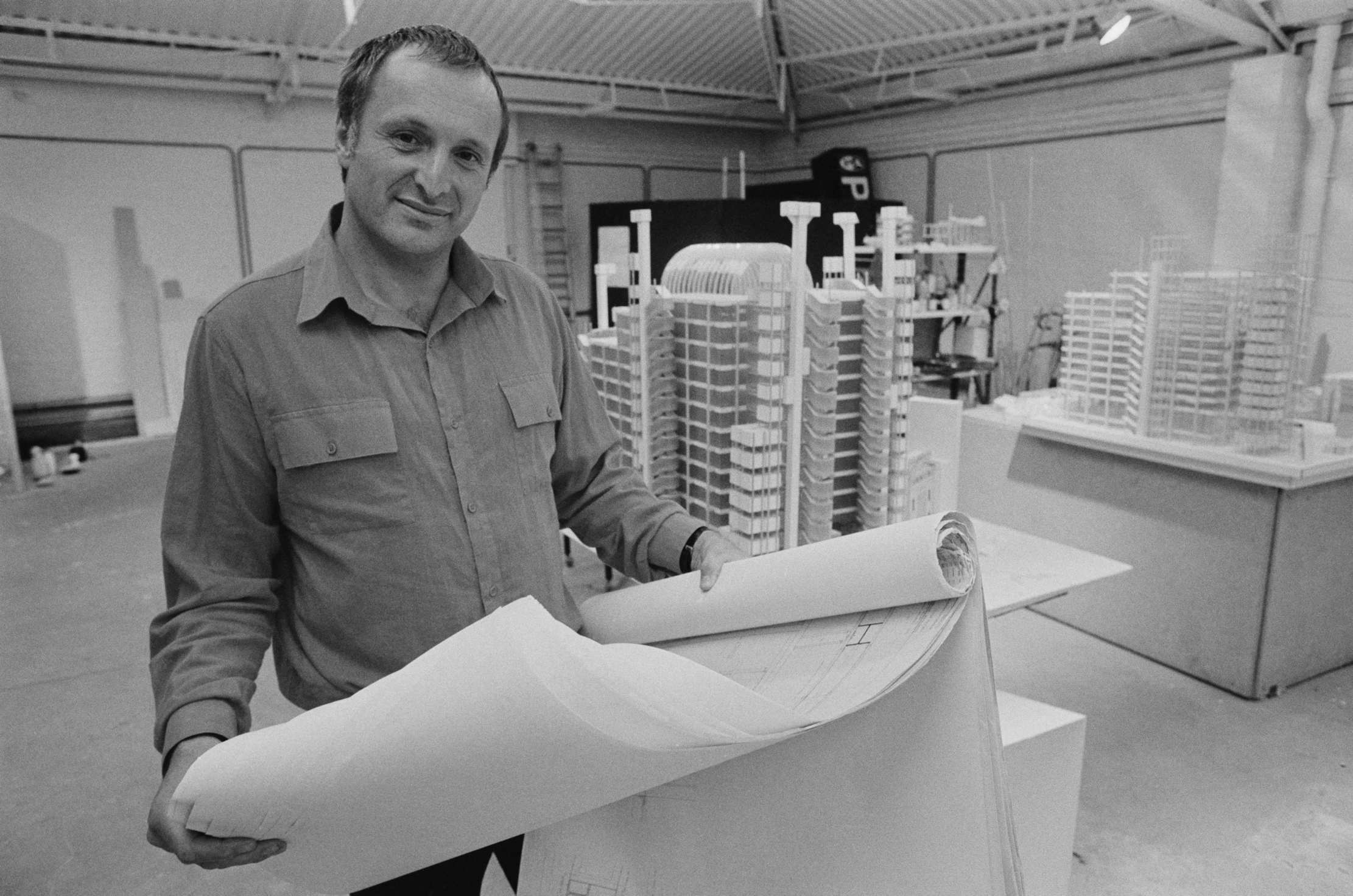

The architect, photographed in his studio in the 1970s.

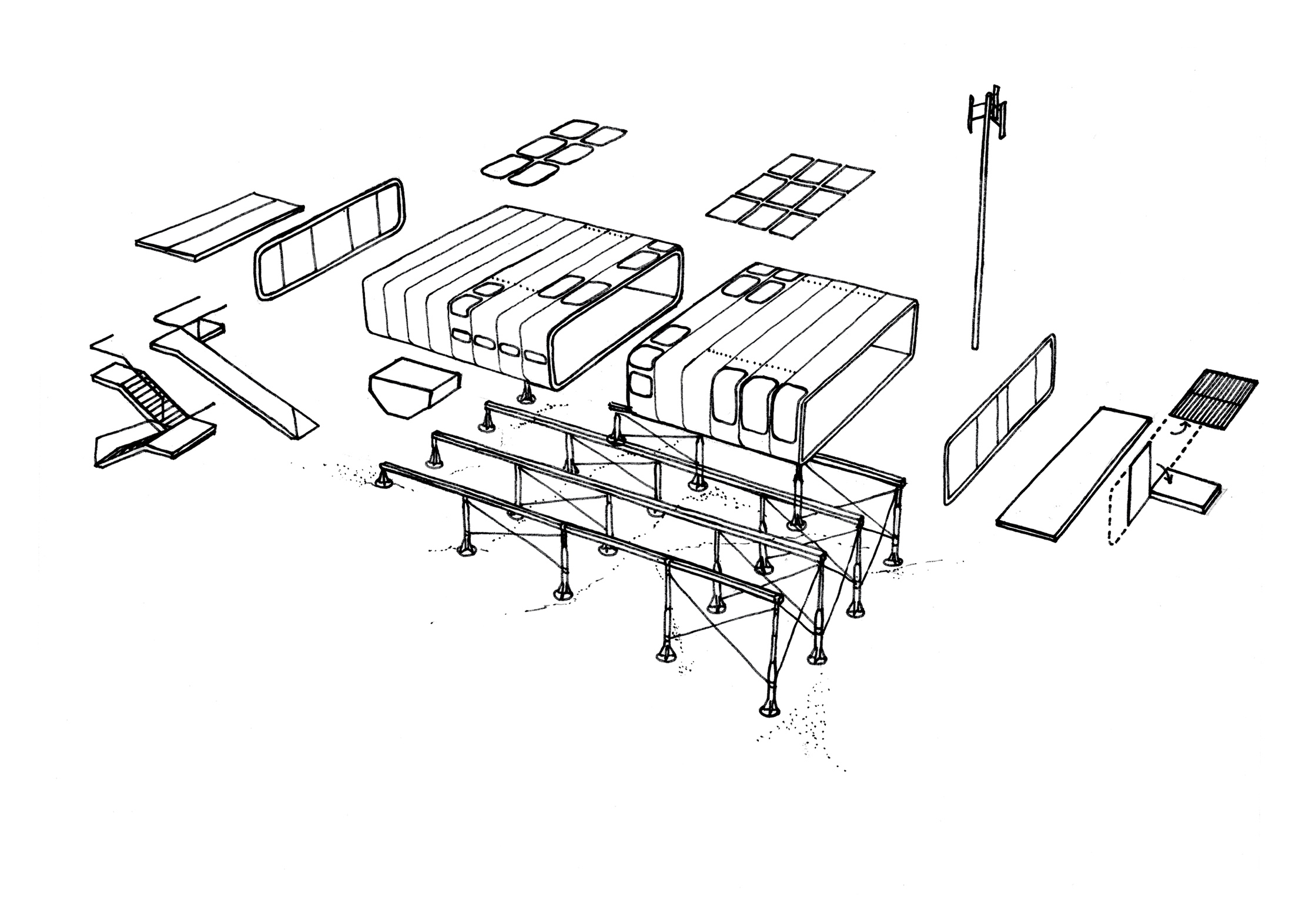

Architecture has long been a form of protest, and it is clear from the start of Rogers’s career that he was an activist. His Zip House (designed 1967–9, but never built), here represented in a scale model and through drawings, was a creation that focused sharply on the necessities of affordable, sustainable and mass produced housing. While never realised, it was an early example of his belief in how the utility of buildings must take priority over all else. It was also an inspiration for the Rogers House, which he built for his parents and was completed in 1970 in Wimbledon.

Both were created to show how buildings could be adapted and imagined around the needs of their users, all while originating from a single elegant design. The Zip House, so named because sections would be ‘zipped’ together, could be formatted into a wide range of configurations and even multiple storeys, and came with adjustable legs to suit placement on any terrain without foundations. The interiors would have been very recognisable to the modern eye, with large open-plan spaces that could be adapted easily.

A drawing of the Zip-Up House, with the individual components shown clearly.

As much as Rogers was interested in creating useful spaces for people to live in, so too was he fascinated by the mechanisms of it all. Throughout his designs, the workings of things are celebrated and elevated, rather than hidden away. Lloyd’s is the obvious example, but so too the Millennium Dome and the Pompidou Centre.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

This almost child-like wonder of the mechanism became a signature of his style, with buildings almost coming apart before your eyes. And he wanted to share that joy, the best example of which is perhaps the Pompidou Centre in Paris, which he designed alongside Renzo Piano. The inner workings of the building were not only made visible, but they were made legible, with a colour-coding scheme (blue for air-conditioning, green for plumbing, yellow for the electrics) adding vibrancy to the design.

Buildings are complex things, but they must also be easy to use and they should be easy to understand. Perhaps that is where Rogers’s real genius lies.

A drawing of the Millennium Dome, as viewed from above.

So much of what ‘good’ architecture is (or, at least, what we believe it ought to be) lies in decoration. Of fine stonework, or soaring glass, or elegant brickwork. Rogers’s work finds beauty elsewhere, in function over form, in utility over ornament. Not that he couldn’t do beauty for beauty’s sake — his Terminal 4 at Madrid’s Barajas Airport is compelling evidence that he could — but rather that beauty can be found in how well a building attends to the needs of its users. After all, while a building can be something worth looking at, its principal function is as a tool, a place to do things. At Lloyd’s that ‘thing’ was a marketplace, so it must be large and spacious and encourage trading. At the Pompidou Centre, it was to ‘inspire curiosity’. The functionality and ever-present focus on a building’s singular purpose is beautiful — at least it was to him.

It was perhaps this overwhelming drive that drew me to Rogers’s work. I had seen many buildings that would be described as ‘beautiful’, but that did not inspire me. It was Lloyd’s that opened my eyes to how good design can elevate a building beyond a piece of stationary art and create something greater. A building designed for the people who use it, with the express purpose of making their lives better.

Lloyd’s, Barajas, The Millennium Dome and the Pompidou may be his grand statements, but it is in his final building, the Drawing Gallery, that it is made clear that Rogers never once wavered from his beliefs. So similar to the Zip Up House in style, the Drawing Gallery protrudes over a vineyard in Provence, France. It is unerringly simple. The exterior, a bright orange exoskeleton, shows you how it all works. The interior is Tardis-like, and adaptable, to suit a range of exhibitions. It bears almost no relevance to the landscape that surrounds it. But what is its purpose? To improve the landscape, or to be an art gallery? The answer is quite clear.

The flowing lines of the interior of Terminal 4 at Barajas Airport in Madrid.

Rogers understood that when it comes to radical ideas, it is more important to show rather than tell. Many of his buildings were heavily criticised when they were first completed, but Lloyd’s became the youngest building to be listed Grade I in 2011, with Historic England describing it as ‘one of the key buildings of the modern epoch’. The results speak for themselves.

This is a small exhibition and it would have perhaps been useful for more to be revealed as to why Rogers believed the things that he did. But in his architecture, there can be no mystery. Everything is laid before you, because you, the user, are the most important thing. And there is beauty in that.

James Fisher is the Digital Commissioning Editor of Country Life. He writes about motoring, travel and things that upset him. He lives in London. He wants to publish good stories, so you should email him.