The Queen's Coronation: The Crowning Day by Ivor Brown

From the Country Life Archive: Ivor Brown reports on the splendid spectacle of the Coronation procession of Queen Elizabeth II. Originally published in the Country Life Coronation Number, June 1953.

RETURN TO THE CORONATION HOMEPAGE

The country, celebrating with its own myriad forms of geniality, the party in the street, the fête upon the green, the beacon blaze upon the hill-tops, could not grudge London its central part in the Coronation on June 2. London had done its best to look the Capital part: there had been little official patterning of the décor. So the huge town beflagged was a People's Palace of Variety; each to his taste and purse. St. James's Street could be nobly august with heraldic blazonings, while the mean streets and sinister streets had their mouldering stucco under every kind of banneret and streamer. The floral dance of fluttering colour was all as free and easy as the "English, unofficial rose" beloved of Rupert Brooke.

"London, thou art the Flower of Cities all." It was a Scot, William Dunbar, who sang it so around the year 1500. That entranced visitor deemed it felicitous as well as blossomy. "Gemme of joy and jaspre of jocundity." And so it was, genially jocund, despite grey skies. This was the first Coronation to send its glorious cavalcade through streets with gaping holes and bomb-blasted chasms still yawning or temporarily covered with the stands and pavilions of the lookers-on. We were saying a sort of farewell to that honourable London of the scars. The joy, was plentifully present, and many a face seemed to echo a popular and charming song of the day, "If I was bell, I'd be ringing." Though the morning hid the sun, this was a London which supplied its own radiation. It was a city with a light in its eyes.

***

It would have been so nice to say that as I left a bed in Fleet Street for a perch in Westminster, rosy-fingered dawn was being appropriately rubious behind St. Paul's. It was, in fact, a leaden-fisted dawn, with an air of murky menace. But at least it was not raining, and the very early marchers to the west and Westminster flaunted their raincoats as though they were mere insurances against the worst. Incidentally, as one discovered later on, a mackintoshed crowd is nowadays a colourful one: as I looked down over the massed pavements about the Abbey I saw a striking assembly of varying blues and reds. Had it been really fine, there might actually have been less colour in its crowd. The rain, or threat of rain, had brought out a rainbow in its coverings.

Those myriads who had sat all night on the pavements contained an astonishing number of grey heads. The people of London were well schooled in 1940 to doss anywhere. To miss a night's sleep and lie on hard surfaces was the experience of every man and every woman; this, as well as cordial loyalty, may in part explain the willingness of so many elder folk to make the pavement a dormitory. On the Monday night I had seen strewn on the steps of St. Martin-in-the-Fields women old enough to have seen three Coronations. The Londoner likes to keep pace with high events, though his own steps may falter with the years. One heard talk among these seniors of the old days, when it was a city of horses and hansoms.

The women, where I was looking on, far out-numbered the men. Age did not matter to them, and age was well tended. The wonderful service of the St. John Ambulance men was not a great deal needed. But what instant provision there was for any who could stand erect no longer! I noted curative tablets, with a small glass of water, emerge miraculously to be handed to a few in need.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

***

I had walked along the Embankment made gay with blue and white festoons and warmed with the new brick of the rebuilt Temple. All this was cheerful, but the heart was lifted anew by two words on a poster. "Everest Climbed." Here was a crowning deed of courage and endurance to greet the crowning day. No date for that long-denied victory could have been fitter.

At Charing Cross the gathering host started to show its papers and its tickets. The organisation was complete. There was no haste or anxious pushing. The way to Westminster was all as tranquil and benign as a walk to church on Sunday morning. Women police were here in charge, and with no sign of fuss and plenty of smiles they ushered the great family party on its way. The pavements were soon to be filled with the schoolchildren, many of whom arrived in festooned river-boats at the landing-stages no less bedecked, the old royal way of progress, as we were reminded by the march of the Queen's Watermen later on. It was sad for some of the young ones that fewer could be squeezed than were accommodated in the same space sixteen years ago. But the reason given for this is, in fact, a happy one. It had been explained that the children of today are so much broader in the beam! Our leanest years have fattened them. "We boast ourselves to be greater than our sires." Well, at least in flesh and bone.

The historic citadel that is the City was the first to send out its champion. Before eight the Lord Mayor's Coach, with attendant pikemen, the Sword Bearer, and the Common Crier, had left the Mansion House. Thus came to Westminster the Middle Ages, gravely, yet gaily, past London's liquid history, as John Burns called the Thames. We had begun. Then "Certain Members of the Royal Family." Then, in multitude, the "Representatives of Foreign States." It would have been better, surely, if each car - for all travelled in closed motor cars - had shown its national flag in miniature, as some indeed did. Without such colourful marking, this element was all rather anonymous and dark. But the Carriage Procession of Prime Ministers, Sir Winston and Lady Churchill leading, lifted the spirits again, and the applauding ceased to be polite, and the cheers came now in thunders from the heart.

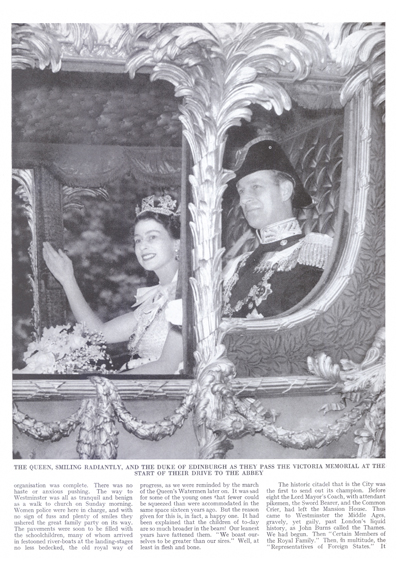

The Queen, smiling radiantly, and the Duke of Edinburgh as they pass the Victoria Memorial at the start of their drive to the Abbey.

From civil powers the procession had swept into royalty, from the motor car to the coach with its pride of footmen and its reminder of ages that were golden at least in their trappings of pomp. The Colonial Rulers came in here and the Queen of Tonga, as mirthful as massive, evoked especial delight with her obvious relish in the day and its doings. So to our own, the Blood Royal of Great Britain, all in their carriages of ancient ceremony, none more handsome than the Duchess of Kent. An escort of Life Guards surged forward in its scarlet before the Glass Coach carrying the Queen Mother and Princess Margaret, who showed their serene pride in the sovereign honours of a daughter and a sister. More and more did one feel the dominating sense of family. The pavements were a mass of households, children to the fore well set to see between the street-lining troops. Here they were the Royal Marines, white-helmeted above blue uniforms and prettily contrasted with the scarlet and gold that was unrolling in the midway. There was the family of Commonwealth, the family of monarchy among the families of Britain and her visitors. How oddly right that the lordly escort of mounted magnificos should bear the simple name of Household Cavalry!

***

Her Majesty's Procession was announced by the roar along the river-bank. In front were grandees on foot, Navy, Army, Air Force and Senior Officers of the Commonwealth. The Queen's Escort of the Life Guards and the Royal Horse Guards supported the baroque magnificence of the State Coach, with its eight greys and postillions. Throughout the day one was reminded that for spectacle even the sleekest of automobiles is a poor match for the horse and rider. Witness the fact that still, in our country and in our age of petrol, the man with a good seat on a good horse will always draw more admiring eyes than any piece of machinery, however streamlined, however powerful.

The timing was perfect. The Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh reached the Abbey to the scheduled moment, bringing their own bounty of fair appearance to perfect the pattern of blue, gold and scarlet in which the were the centre. The crowning was at hand.

***

Many on the east side of Westminster had seen all they were able to see unless they could somehow be wedged into the westward crowd or get to a new vantage-point for the longer procession of the afternoon. The rain, which had mercifully delayed its onset, came down during the Service and for a short while after, but it dutifully lifted just as the crowned Queen came out with the Duke to undertake the long, circuitous return to the Palace for which a patient people had been waiting in mass along the great streets of the West End and waiting all over the country, also in order to partake, by ear or by view of the television screen, in this extraordinary day. A glimpse of sunshine raised the panoply of State to a higher power: even without the sun the brilliance of the old days, when a fighting man was a dandy and a carriage was a palace in miniature, fought and defeated the morose and grudging weather. It was a triumph of man over nature. The drabness of a modern, smoke-smutched city had been vanquished by the decorations: the drabness of a far less than glorious June was gallantly beaten off by our heritage of ceremonial splendour. There were bells and fanfares, drums and far-off salvos for the ear, colour in marching rhythm for the eye.

***

It was good to see the Earl Marshal escorting all the great ones to their carriages and coaches for the second procession. He and his colleagues had indeed done the marshalling task beyond criticism. To direct such a host of personalities and troops within such a confined area and with such faultless observance of time and proportion was, of course, the work of arduous months. That work had its reward in these few crowded hours of glory and precision mixed.

"In my end is my beginning." When Queen Victoria was crowned, many people were muttering that this might be the last of our Coronations. When she died, there could be nobody to say that again. When her great-granddaughter was crowned, everybody knew that for the British monarchy this was "the top of happy hours." During the century a great problem of power had been solved, by division of power. The Government of the day was as easily dismissible, at popular will, as any employed person. The Crown, by popular consent, was the emblem of permanence, of tradition with dignity, of splendour without arrogance, the enduring symbol of union in nation and in Commonwealth.

***

These things are well known. Less common perhaps, has been the tribute to the Crown's aesthetic value. The Coronation, so warmly welcomed by a people nervous of exhibitionism and little given to pageantry, is a precious reminder that the Monarch and its royal panoply are first among our great assertions of coloured splendour, our testaments of beauty. The personal beauty of the Queen has given especial point to this national essay in the superbly spectacular. The people of a country whose legacy includes such wealth of landscape and of great buildings, public and private, sacred and secular, buildings which ride the land with poise like fine riders on fine horses, are shown that pomp is not a thing for shame, if it be free of pride and vanity.

The procession passing through the Admiralty Arch and across Trafalgar Square towards Northumberland Avenue.

Pomp, in its true, processional sense, is a thing to lift the heart by taking the eye. We are apt to be humdrum, even drab, in our workaday lives, but there is behind us a blaze of beauty in our social history and there is before us, if we take our chances, the power to keep what is left of the ancient elegance while seeking new styles not unworthy of the old. The two Coronation processions, as I watched them from a window in Westminster, seemed far more than political and civic demonstrations. They were tributes to our submerged, but yet undying, instinct for rare and lovely things. The sour few who can still dismiss such an occasion as an out-dated pantomime are overlooking a valid fact. The Monarchy, with its Royal Standard, is holding high a standard of loveliness in public life, of joy in design and decoration as well as of modesty in conduct and decorum.

***

Among the ordinances set before the Queen in the Coronation Service is a charge "to restore the things that are gone to decay and maintain the things that are restored." The Monarchy is one of our guards against the vandal, one of our assertions that, in the world of use, beauty is no vanity, but chief among all useful things.

RETURN TO THE CORONATION HOMEPAGE

READ: IN THE ABBEY BY JOHN BETJEMAN

READ: THE CORONATION CHURCH BY LAWRENCE E. TANNER

READ: A PORTRAIT OF QUEEN ELIZABETH II

READ: A PORTRAIT OF THE DUKE OF EDINBURGH

Agnes has worked for Country Life in various guises — across print, digital and specialist editorial projects — before finally finding her spiritual home on the Features Desk. A graduate of Central St. Martins College of Art & Design she has worked on luxury titles including GQ and Wallpaper* and has written for Condé Nast Contract Publishing, Horse & Hound, Esquire and The Independent on Sunday. She is currently writing a book about dogs, due to be published by Rizzoli New York in September 2025.

-

How many bees, Channel 4 and a Catch 22: Country Life Quiz of the Day, May 6, 2025

How many bees, Channel 4 and a Catch 22: Country Life Quiz of the Day, May 6, 2025Tuesday's Quiz of the Day features a famous road, nature and science.

-

Tasburgh Hall: From a Buddhist centre to a seven-bedroom family home in 23 acres

Tasburgh Hall: From a Buddhist centre to a seven-bedroom family home in 23 acresThe property, in Norfolk, was once four separate apartments, but has been lovingly re-stitched back together.