'If your boyfriend makes carbonara with pancetta or bacon, break up': Tom Parker Bowles on how to make a classic carbonara

Getting to grips with a Roman classic.

'Pasta alla carbonara is from Rome,’ growls Andreas Viestad in his delightful 2023 book, Dinner in Rome: A History of the World in One Meal, ‘and it should contain guanciale, eggs, pasta and pecorino. If you’re lacking any of this,’ he goes on, ‘it is not pasta alla carbonara. If you’ve added something, it is not pasta alla carbonara either.’ Viestad may be a Norwegian by birth, but when it comes to this particular plate of pasta, he’s Roman to his very core.

Because this is one regional Italian classic that manages to both soothe and inflame. Made properly, it’s comfort food clad in Brioni blouson, a magical emulsion of egg yolk, pasta water and pecorino clinging concupiscently to each glossy strand of pasta. Any excess of Lucullan lavishness is tamed and tempered by crisp, salty nuggets of cured pig jowl and a healthy blast of black pepper. You don’t want too much of it either, as carbonara is as rich as Crassus and should always leave you begging for just one bite more.

Carbonara also tops a list, published by the Accademia Italiana della Cucina, of the most commonly falsified Italian recipes. You’ll find heretics who add garlic, infidels who insist on onions and, worst of all, cretinos who think that cream adds to its lustre. Basta! Purists will also insist (as they always do) on guanciale and guanciale alone, arguing that only this particularly hardworking part of the pig’s head has the depth of flavour, and sweetness of fat, to give the dish its unique savour. Some see it as an insight into the cook’s very character. ‘If your boyfriend makes carbonara with pancetta or bacon, break up,’ goes a typically Italian piece of romantic advice. But as Rachel Roddy argues in Five Quarters: Recipes and Notes from a Kitchen in Rome, pancetta is fine. Some Romans, she whispers, even prefer it.

This is a recipe that is at once straightforward and a touch intimidating. Timing is key, as carbonara waits for no man. The freshly drained pasta must be poured into the pan in which you fried the pork, the pan taken away from the heat. Then the egg and cheese mixture is added, together with some reserved cooking water. Too much of that, however, and you’ll end up with a thin sauce that doesn’t stick to your pasta. An excess of heat and the mixture will congeal into porky scrambled eggs. Practice, as ever, makes perfect.

'There’s nothing wrong with adding whatever you want to your sauce. Even, dare I say it, a dash of cream. Just don’t, for Jupiter’s sake, call it carbonara'

There are endless different tales as to how the dish came about. There always are.

Some say it was named after the charcoal burners (carbone is the Italian for charcoal and coal) who ate the dish when working the forests around Rome; others insist it was a firm favourite with coal sellers and that the pepper is a reminder of the coal dust that fell from clothes to plate as they ate. One particularly romantic yarn contends carbonara was created in tribute to the Carbonari, a secret society of freedom fighters determined to overthrow Napoleon, when he pronounced himself King of Italy. But that seems a little less credible, as the Carbonari were based in Naples, a city with little time for Roman ways.

Much of the confusion comes from there being no record of the recipe until after the Second World War. Although similar dishes were widely cooked (pasta alla gricia, cacio e pepe and so on), one of the more plausible theories claims that it was an American-Italian hybrid — US soldiers in post-war Rome would give their rations of powdered egg, bacon and cheese to local chefs, who then created this sort of egg and bacon atop spaghetti. Food was painfully scarce in those post-war days, unless you were an American GI, so this theory is less outlandish than it may initially seem.

The Americans certainly took the recipe home with them to the US, where cooks were less than fussy about any so-called ‘authenticity’. And, to be honest, there’s nothing wrong with adding whatever you want to your sauce. Even, dare I say it, a dash of cream. Just don’t, for Jupiter’s sake, call it carbonara.

Spaghetti alla carbonara

This comes from Rachel Roddy’s Five Quarters, a modern Roman classic and a book I turn to again and again — not only for the depth of research, but the quality of the writing, too. It’s as much fun to read as it is to cook from and each page is scented with the very essence of the Eternal City.

Ingredients

Serves 4

150g guanciale, pancetta or bacon

450g spaghetti

A little olive oil

2 whole eggs and 2 extra yolks

80g grated pecorino or Parmesan—or a mixture of both

Salt and freshly ground pepper

Method

• Bring a large pan of water to a rolling boil. Cut the guanciale into short, thick strips. In a large pan over a moderate heat, cook the guanciale in a little olive oil until the fat has rendered and the pieces are golden and crisp. Remove from the heat.

• Add salt to the boiling water, stir, then add the spaghetti, fanning it out and using a wooden spoon to gently press and submerge the strands. Cover the pan until the water comes back to the boil, then remove the lid and continue cooking until it is al dente (check the cooking time on the packet and start tasting at least two minutes earlier).

• While the pasta is cooking, in a largish bowl whisk together the eggs, egg yolks, grated cheese, a pinch of salt and plenty of black pepper. Heat up the meat pan again and, once hot, use a slotted spoon to remove three-quarters of the guanciale pieces onto a small plate, leaving the last quarter and the fat in the pan.

• Drain the pasta, reserving a cupful of the cooking water. Add the pasta to the frying pan, stirring so that each strand is coated with fat. Turn off the heat, then add the egg and cheese mixture, and a little cooking water. Using a wooden spoon or fork, mix everything together vigorously so that each strand is coated with a creamy sauce. Add just a little more cooking water if the sauce is too stiff. Serve immediately, dividing the rest of the crisp guanciale between the plates.

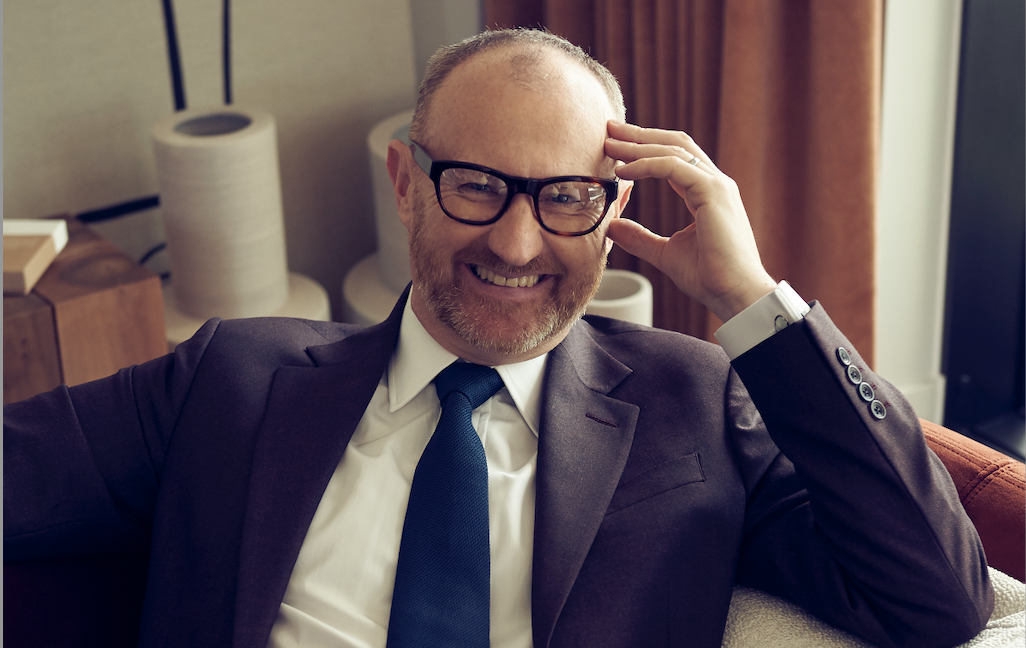

Tom Parker Bowles is food writer, critic and regular contributor to Country Life.

-

A Georgian farmhouse that's an 'absolute gem' in an ancient village on Salisbury Plain

A Georgian farmhouse that's an 'absolute gem' in an ancient village on Salisbury PlainJulie Harding takes a look at the beautiful West Farm in a gorgeous Wiltshire village.

-

Can you guess the landmark from its gingerbread copy cat? Take our quiz

Can you guess the landmark from its gingerbread copy cat? Take our quizToday's quiz takes a detailed look at the gingerbread works on display at London's The Gingerbread City — and asks if you can guess which iconic landmark they are.

-

Sweet civilisation: What do you get when you ask architects to compete in a gingerbread competition?

Sweet civilisation: What do you get when you ask architects to compete in a gingerbread competition?The Gingerbread City is back in London’s Kings Cross. Lotte Brundle pays it a visit.

-

Sophia Money-Coutts: A snob's guide to meeting your in-laws for the first time

Sophia Money-Coutts: A snob's guide to meeting your in-laws for the first timeThere's little more daunting than meeting your (future) in-laws for the first time. Here's how to make the right kind of impression.

-

This machine is what happens when the Rolls-Royce of motorbikes and the most innovative of watchmakers join forces

This machine is what happens when the Rolls-Royce of motorbikes and the most innovative of watchmakers join forcesBrough Superior and Richard Mille, two brands renowned for perfection, have created something that is exactly that.

-

‘Each one is different depending on what mood I’m in, how I'm feeling and how my energy is’ — meet the carver behind Westminster Hall's angel statues

‘Each one is different depending on what mood I’m in, how I'm feeling and how my energy is’ — meet the carver behind Westminster Hall's angel statuesBespoke woodcarver William Barsley makes unique scale replicas of the angels that gaze over Westminster Hall, the oldest part of the palace of Westminster.

-

What is everyone talking about this week: Thanks to modern-day technology, people were far happier in the days when Nero was setting Rome ablaze

What is everyone talking about this week: Thanks to modern-day technology, people were far happier in the days when Nero was setting Rome ablazeWas the ancient world's superior happiness down to its ‘superior production of art’?

-

A slick looking off-roader that's a far cry from its rustic rural roots — Volvo EX30 Cross Country

A slick looking off-roader that's a far cry from its rustic rural roots — Volvo EX30 Cross CountryThe latest iteration of Volvo's Cross Country is flashy, fast and stylish. But is that what a Volvo Cross Country is supposed to be?

-

‘I cannot bring myself to believe that Emily Brontë would be turning over in her grave at the idea of Jacob Elordi tightening breathless Barbie’s corset’: In defence of radical adaptations

‘I cannot bring myself to believe that Emily Brontë would be turning over in her grave at the idea of Jacob Elordi tightening breathless Barbie’s corset’: In defence of radical adaptationsA trailer for the upcoming adaptation of 'Wuthering Heights' has left half of Britain clutching their pearls. What's the fuss, questions Laura Kay, who argues in defence of radical adaptations of classic literature.

-

Mark Gatiss: ‘BBC Two turned down The League of Gentlemen six times’

Mark Gatiss: ‘BBC Two turned down The League of Gentlemen six times’The actor and writer tells Lotte Brundle about his latest Christmas ghost story, discovering Benedict Cumberbatch — and his consuming passions.