'It’s always been more about the things than the money': The family crafting silk for Strictly, Highgrove, the House of Commons and Westminster Abbey

For half a century, Beckford Silk has been supplying remarkable textiles since 1975. Ben Lerwill discovers what makes its wares materially different

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Fine silk accessories might be delicate, gossamer things, but they’re not light work to make. Each scarf, tie or pillowcase is the product of toil and experience, their patterns and colours brought into being by perfectionists who know their crêpes de chine and chiffons like the backs of their hands. Such is the case with Beckford Silk, a Cotswold family business established half a century ago. ‘What we produce,’ explains octogenarian and family patriarch James Gardner, leaning over a winch-dyeing machine, ‘really matters to us.’

The company’s story is an inspiring one. It was founded in 1975 by James and his wife, Marthe, in the small Gloucestershire village of Beckford, where it remains today. The couple had met when Marthe, originally from France’s Haute-Savoie region, came to England as an exchange student. The two were introduced and James offered to paint her portrait. A fortnight later, they were engaged.

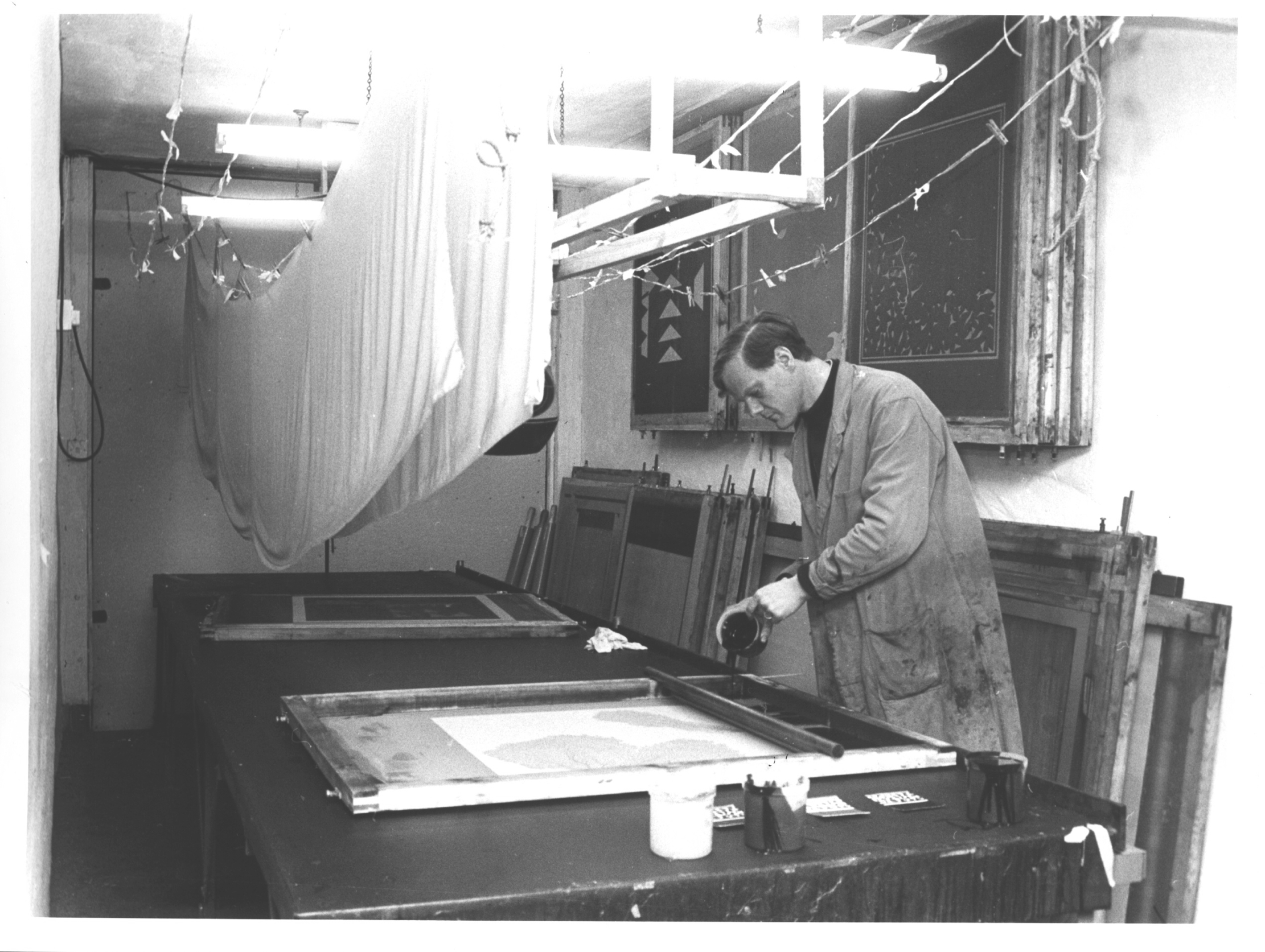

James Gardner printing in his studio.

Being a creatively minded couple, they soon resolved to launch a small business making beautiful things, by hand, in the countryside. ‘Textile printing in particular really appealed,’ notes James. ‘You can make such wonderful use of colour.’ The ethos of the Arts-and-Crafts Movement, which had held sway in this part of the Cotswolds in the late 19th century, was a guiding influence. Beckford Silk was born.

Five decades on, its list of clients is prestigious, including Highgrove in Gloucestershire, the House of Commons and Westminster Abbey, the V&A Museum, the Tate and the Royal Academy of Arts. If you’ve been to a leading UK gallery and found your eye caught by a finely printed silk scarf in the gift shop, there’s a very good chance it originated in Beckford. Even the BBC’s Strictly Come Dancing is no stranger to ringing in with last-minute orders, in search of lengths of lustrous fabric for its stage sets.

In the early days, however, the company’s big break came by chance. Lacking a premises to call their own, the Gardners began by printing partly at home and partly in the skittle alley of the family restaurant in nearby Tewkesbury, a space that gave them the necessary dimensions to set up lengthy printing tables. It so happened that the National Trust’s leadership team, based locally, was in the habit of taking weekly lunch meetings at the same restaurant. When the team members’ attention was piqued by James, bent over textiles, they took a closer look and were impressed by what they saw. Beckford Silk’s first major commission followed soon afterwards.

By the late 1980s, the company’s reputation for design and hand-printing — as well as the success of its accessories in the burgeoning ‘heritage retail’ industry — meant the couple was able to construct a purpose-built headquarters on the outskirts of the village. This attractive red-brick complex, today open to visitors and home to a café, is still very much the heartbeat of operations. With James and Marthe's daughter Anne Hopkins and their son Robbie Gardner also working full time for the business — as director of sales, and design and production director respectively — it now stands as a family firm with more than 50 years of expertise.

Silk scarves are a speciality, although it’s worth stating that silk, despite its luxurious associations, is not an especially lucrative industry. ‘Many years ago, Dad told me there are two kinds of people in this world,’ remembers Anne. ‘People who make money and people who make things. That says a lot. It’s always been more about the things than the money.’

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The Columbines, Periwinkles and Sweetpeas scarf made by Beckford Silk for the V&A Museum features A. F. Vigers’s wallpaper design of the same name, dating from 1901.

The company’s collaborations with many of the country’s leading artistic and cultural institutions are testament to this passion. Clients are given a choice of about two dozen quality silk weaves, from habotai, organza and chiffon to charmeuse, georgette and jacquard. All are sourced directly as natural white silks from China’s Zhejiang province and all feel slightly different to the touch. These silks are then used as vehicles for the colours, styles and designs requested by the client, which might be anything from Rembrandt-themed scarves for the National Gallery to mosaic-patterned scarves for St Paul’s Cathedral. Some clients simply request a certain quantity of plain dyed silk.

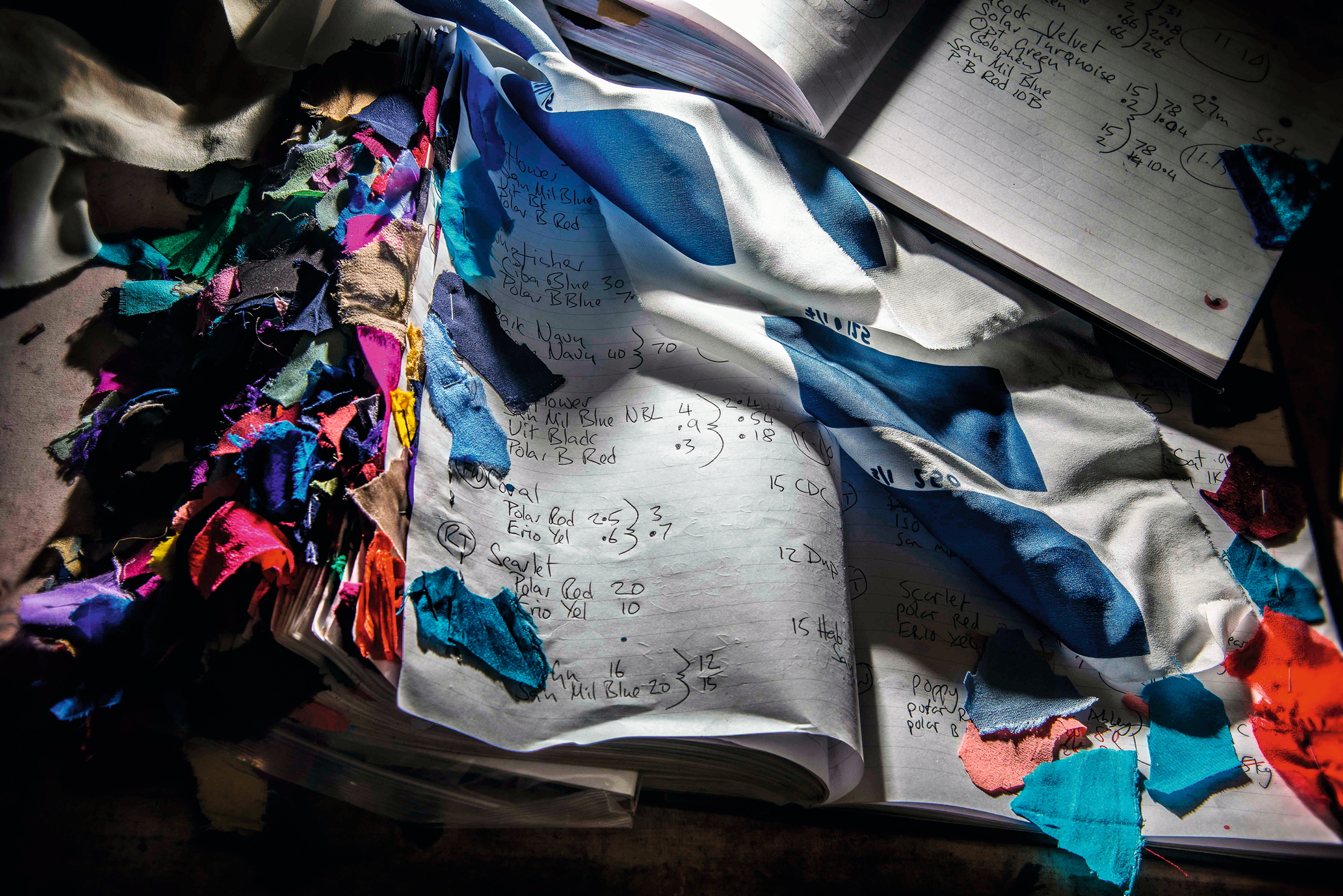

Scarf designs are worked on in house, using a mixture of hand work and computer assistance, before being printed using either digital or screen printing. The fabrics themselves, however, need to be dyed before this stage, which is a delicate and time-consuming skill.

James, who turns 88 in December this year, remains the main dyer and colourist for commissions that come in. ‘Dad’s still in charge,’ laughs his son, going on to explain the intricacy of the dyeing process. He points out an extensive shelving unit of dyes: rows of well-used jars containing brilliant blues, violets and rubines. Finding an exact match for the required colour needs a trained eye and that’s only half the job. ‘Silk is very hard to dye,’ he confirms. ‘It needs real care. Half a gram of dye can be enough for 39ft of cloth.’ For darker colours, barely more is required: merely a few grams for the same amount of material.

Using the winch-dyer, a length of fabric is sewn into a loop, wrapped around a winch and rotated steadily through the water-diluted vat of dye. One of the things that sets Beckford Silk apart from its mass-market competitors is that it accepts jobs of all sizes. ‘We’re the only commercial dyers in the country,’ says Robbie. ‘We specialise in small quantities, whereas most of the industry isn’t interested in anything under a certain number of metres.’

Marthe Gardner. She founded Beckford Silks with her husband in 1975.

The other key factor in the quality of the firm’s products is its finishing machine, the stenter, which heats, dries and finishes the silk to smooth out any creases. Stretching for almost 33ft from end to end in a series of clips and rumbling conveyors, it is twice the age of Beckford Silk itself. ‘A modern stenter will cost up to £500,000, but this was made in 1924 by an Oldham firm called Mather & Platt,’ observes James, carefully feeding a length of fuchsia silk into its antique workings. ‘It really is a wonderful bit of engineering.’

In the case of the scarves, the process is complete when the panels are checked, then have their edges hand-rolled and sewn. Dyed fabric lengths, meanwhile, are sold both in the on-site shop and online. The end products are rainbow-bright, but somehow have the feel of something from another time — an apt description, perhaps, for a company where traditional methods and values aren’t so much a passing trend as an overriding principle.

Ben Lerwill is a multi-award-winning travel writer based in Oxford. He has written for publications and websites including national newspapers, Rough Guides, National Geographic Traveller, and many more. His children's books include Wildlives (Nosy Crow, 2019) and Climate Rebels and Wild Cities (both Puffin, 2020).