Kenneth Grahame and the true meaning behind The Wind in the Willows

The Edwardian author Kenneth Grahame’s adoration of Nature and landscape made him passionate about conservation and inspired him to create some of Britain's best-loved characters, says his biographer Matthew Dennison.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

With a shudder, readers of The Wind in the Willows will remember ‘the cold still afternoon with a hard steely sky overhead’ when Mole slips silently from Rat’s parlour on his journey to discover Badger ‘in his hole in the middle of the Wild Wood’. For many readers, Mole’s snowy tribulations blot out the inventory of summer wildflowers with which author Kenneth Grahame prefixes Mole’s adventure – what Grahame describes as ‘the pageant of the river bank’: purple loosestrife, willow-herb, purple- and white-flowered comfrey, dog roses and meadowsweet.

Look again at Grahame’s descriptions, in which each of these wildflowers is personified, and what emerges is a writer deeply in thrall to Nature’s beauty.

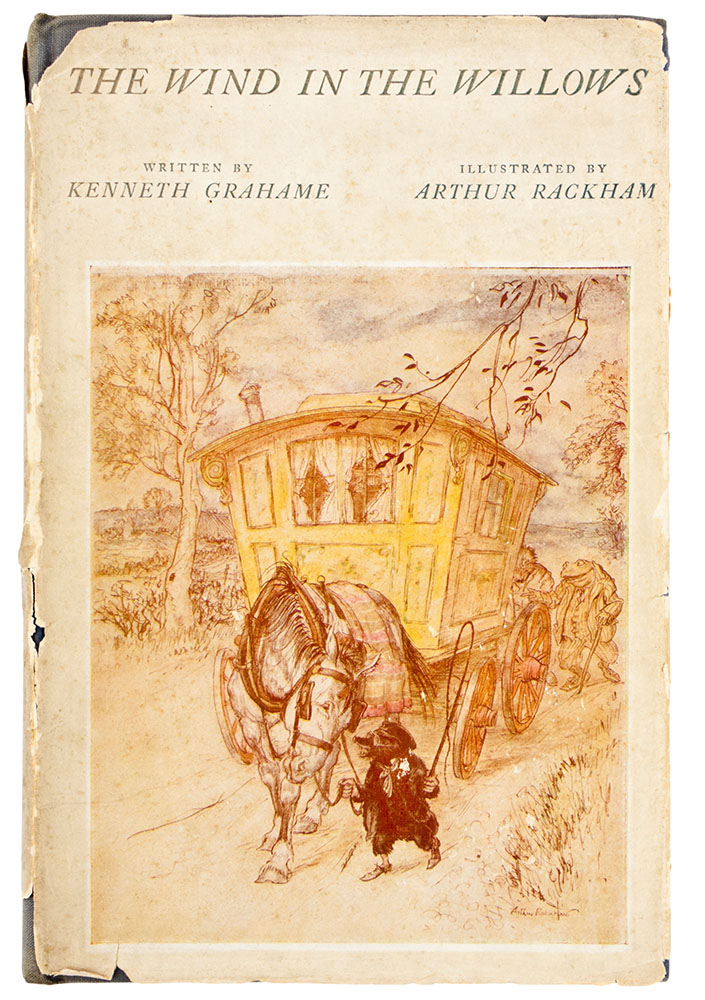

On publication 110 years ago, The Wind in the Willows – Grahame’s only full-length fiction – was met with lukewarm, even hostile reviews. Memorably, the Times Literary Supplement dismissed it as ‘nonsense of poor quality’ and ‘as a contribution to natural history… negligible’.

Granted, Grahame employed a degree of creative licence. Each of his riverbankers is first and foremost a leisured Edwardian bachelor: Mole, for example, has a black velvet smoking jacket and, as Beatrix Potter fulminated, Toad combs his hair.

‘I like most of my friends among the animals more than I like most of my friends among mankind.'

With hindsight, the novel’s contribution to natural history is considerable. Grahame’s story of boating, caravanning and picnicking and the hijinks of a cross-dressing amphibian is also a paean to the English landscape and Nature’s bounty, Grahame’s celebration of the ‘treasures of hedge and ditch; the rapt surprise of the first lords-and-ladies, the rustle of a field-mouse, the splash of a frog’.

The book’s setting is deliberately idyllic and it conjures up images of meadow, bank and wood as lovingly as John Clare or William Wordsworth, with the crispness of observation of an engraving by Thomas Bewick. All that’s absent are willows themselves, never mentioned by Grahame, who had provisionally entitled his book ‘The Mole and The Water Rat’ (the final title appears to have been his publisher’s decision).

Grahame discovered Nature as a child. In a life punctuated by personal unhappiness (the early death of his mother, his father’s alcoholism, his own unsuccessful marriage and the suicide of his only son), Nature and landscape provided his principal joys.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

He once told his wife that, although she was interested in people, what moved him were places; he might truthfully have added the community of wildlife that populated his favourite places. ‘I like most of my friends among the animals more than I like most of my friends among mankind,’ he once wrote.

Time would harden his conviction ‘that nature has her moments of sympathy with man’ and he was a young man when he replaced conventional Christian orthodoxies with something closer to animism – a belief in the living soul of all natural things. Grahame was never a churchgoer: his spiritual experiences took place outdoors.

Faced with a difficult decision, he explained that he ‘would go forth once more’ on the Berkshire Downs within sight of his house ‘and give it prayerful consideration among my friends the hares and plovers’. He was born in Edinburgh in 1859.

He spent his earliest years in houses on the banks of Loch Fyne in Argyllshire, still then a remote rural location, scarcely disturbed by the new railways. His first memories were of the ‘hurry and scurry’ of the pierside, fisherfolk and nests of water voles along the banks of the Crinan Canal.

'Grahame retreated from overwhelming sadness into an imaginary world inspired by Nature.'

In the aftermath of his mother’s death, together with his three siblings, five-year-old Grahame left Scotland. He travelled 500 miles south, to the home of his maternal grandmother in Cookham Dean. The Mount was a higgledy-piggledy old house, with leaded windows, half-timbering, towering chimney-stacks and its roof of clay tiles well weathered.

Within walking distance of its large garden lay dense, dark, thickly carpeted Quarry Wood, the model for the Wild Wood, and a broad ribbon of the Thames, slowed by weirs and overhung by alders and willow trees.

Too young to understand the fullness of his grief for his mother, at The Mount, Grahame retreated from overwhelming sadness into an imaginary world inspired by Nature. He became a daydreamer, his surrounds the catalyst for his dreams. ‘If you lay down your nose an inch or two from the water,’ he wrote later, remembering his grandmother’s lily pond, ‘it was not long ere the old sense of proportion vanished clean away.

The glittering insects that darted to and fro on its surface became sea-monsters dire, the gnats that hung above them swelled to albatrosses, and the pond itself stretched out into a vast inland sea.’

Grahame and his siblings spent two years at The Mount, before a storm brought down one of its chimneystacks, forcing the family to move. He retained the memory of this short interlude his whole life and returned to it repeatedly as a balm to heal his suffering. It was at The Mount that, like Rat in The Wind in the Willows, he became ‘a self-sufficing sort of animal, rooted to the land’.

'Sometimes, he turned away from the path to lie down on empty stretches of thin grass and he liked to imagine that Nature had absorbed him bodily, his sense of himself willingly surrendered.'

Grahame’s intense love of Nature survived the three decades he lived mostly in London, working at the Bank of England, latterly as one of its most senior administrators. As a young man, he spent his weekends walking the hills and chalk paths of the Thames valley. Deliberately, he returned to the landscape of his childhood, that stretch of river that links Cookham Dean to Cranbourne and, beyond, to Blewbury, where, afterwards, he settled with his wife, Elspeth, and son Alastair or ‘Mouse’.

One weekend, he set off from the Thames-side village of Streatley to explore the Ridgeway, following ‘a broad green ribbon of turf’ that sliced through an ‘almost trackless expanse of billowy Downs’, until he reached Cuckhamsley Hill, 10 miles distant.

He revelled in the silence and, in the 1880s, the absence of fellow walkers, ‘alone with the southwest wind and the blue sky’, only sheep for company, the only disturbance the whisper of thin breezes.

Such solitary excursions became visionary experiences for Grahame. Sometimes, he turned away from the path to lie down on empty stretches of thin grass and he liked to imagine that Nature had absorbed him bodily, his sense of himself willingly surrendered.

There were, he argued, two Englands that existed side by side. One was the bustling busy country shaped by technological progress and the advances of the Industrial Revolution. Grahame preferred an older England ‘of heath and common and windy sheep down, of by-lanes and village greens’.

This is the outlook that shaped The Wind in the Willows, a combination of anxious conservatism and rapturous marvel at Nature’s glories.

The novel exists on several levels and the story of Toad’s rollicking adventures – invariably, children’s favourite element – is only one aspect of a book that, in revisiting with animal characters Jerome K. Jerome’s Three Men in a Boat of 1888, becomes a lyrical commemoration of a world on the brink of change: the Edwardian rural England that swiftly fell prey to Income Tax and death duties, the changes of the First World War, the arrival of the motorcar and sprawling suburbs.

‘Year by year I see things I have admired and loved passing and perishing utterly,’ Grahame wrote. In the pages of his much-loved novel, they survive forever.

‘Eternal Boy’, Matthew Dennison’s biography of Kenneth Grahame, is published by Head of Zeus.

Credit: Alamy Stock Photo

Our six favourite nannies, in fiction and film

Whether they invoke fond or fearful memories in real life, the nannies of fiction are kind – even magical –

Credit: Strutt & Parker

The country retreat where JM Barrie dreamed up Peter Pan to entertain three young houseguests

Set on 1.5 acres of land on the edge of Bourne Wood, Lobswood House has been sympathetically renovated to retain

Credit: Alamy Stock Photo

The best books to give this Christmas

Emily Rhodes suggests eight books that would make the ideal literary stocking filler.

We recreated Three Men in a Boat for the 21st century. Here's what happened.

Re-creating Jerome K. Jerome’s Three Men in a Boat sounds terribly romantic, doesn’t it? Patrick Galbraith discovers the reality of

Credit: Alamy

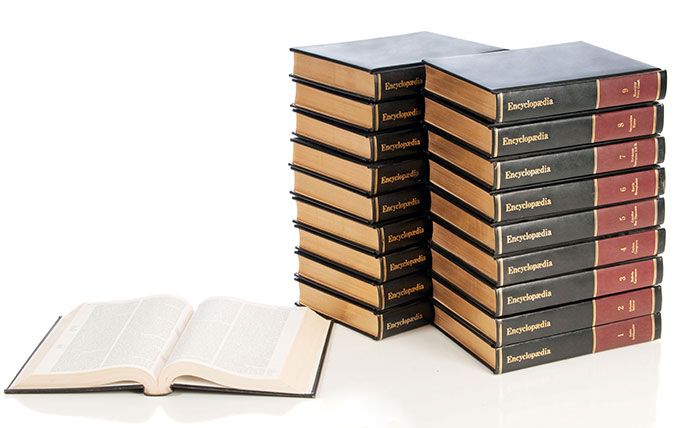

Curious Questions: Is there any future for Encyclopedia Britannica?

Once the first set of books required in any home library, encyclopedias have long since been superseded by the internet.