‘People would rather buy 20 synthetic jumpers than a woollen one that would last them a lifetime’: The British wool trade today

Sheep shearing was king in the middle ages, writes Lotte Brundle, but the rise of synthetic fibres put the industry in a woolly position. How is it faring now?

Harry Pearson

To be a sheep, in the middle ages, was akin to having a coat made out of gold. Such was the value of the wool industry. British Wool (also known as The British Wool Marketing Board) celebrates its 75th anniversary this month. In that time, British sheep have produced the equivalent of 13 billion pairs of socks — enough to give each person in the UK 187 pairs. The farmers’ organisation represents around 30,000 registered wool producers across the UK, so, to mark the occasion, Country Life is taking a look back across the history of the trade that once dominated this country’s economy.

The president of the re-formed Cotswold Sheep Society, Mr W Garne, looking at some of his flock of Cotswold sheep in the shearing pens.

One sheep's fleece is another man's fortune

The sheep, the whole sheep, and nothing but the sheep: how much does it cost?

Fleece — cost: 26p. Used for: wool, felt, loft insulation, carpeting, knitwear, tennis balls

Skin — cost: £65 per square metre (about £10 per sq ft). Used for: rugs, gloves, jackets, slippers, paint-rollers

Lanolin — cost: £89 per kilo. Used for: shaving soap, moisturiser, medicated shampoo, waterproofing

Fat — cost: £4 per kilo. Used for: soap, candles, floor-wax, crayons, deep-frying

Bone, hoof and horn — cost: £2 per kilo. Used for: gelatine, dice, piano keys, photographic film, glue

Intestines — cost: 85p per metre. Used for: sausage casings, racquet and violin strings, surgical ligatures

Milk — cost: £1 per litre. Used for: cheese, soap, ice cream

Note: prices are approximate. Cost of fleece is what the farmer receives; sheepskin and meat prices are consumer prices if buying direct; other costs wholesale.

Wool used to be of the utmost importance in medieval society. It had the power to transform subsistence farmers into wealthy men. Many of the most prized breeds of sheep were not even milked, out of the fear that this might reduce the quality of their fleeces, such was its importance. One Cotswold’s breed, the Ryeland, had wool so valuable people nicknamed it the ‘Leominster ore’. It was even prized among royalty; an Act of Parliament made in 1341 granted the monarch an annual 30,000 sacks of wool.

As time went on, the popularity of wool only grew. The English exported raw wool to Europe at first until, thanks to the arrival of Flemish master weavers in 1331, a booming cloth trade was created. In the 1700s, woollen cloth made up more than half of our export trade, today it makes up less than 2%. For this, we have the Industrial Revolution and the Lancashire cotton trade to blame. In the 1950s, further problems plagued British wool: namely cheap imports from overseas and the rise of affordable polymer-based fibres. Then, in the 1980s, polar fleece arrived, unravelling the industry further. Synthetic fleece dealt it a further savage blow and in 2020 sheep fleece value was at its lowest ever.

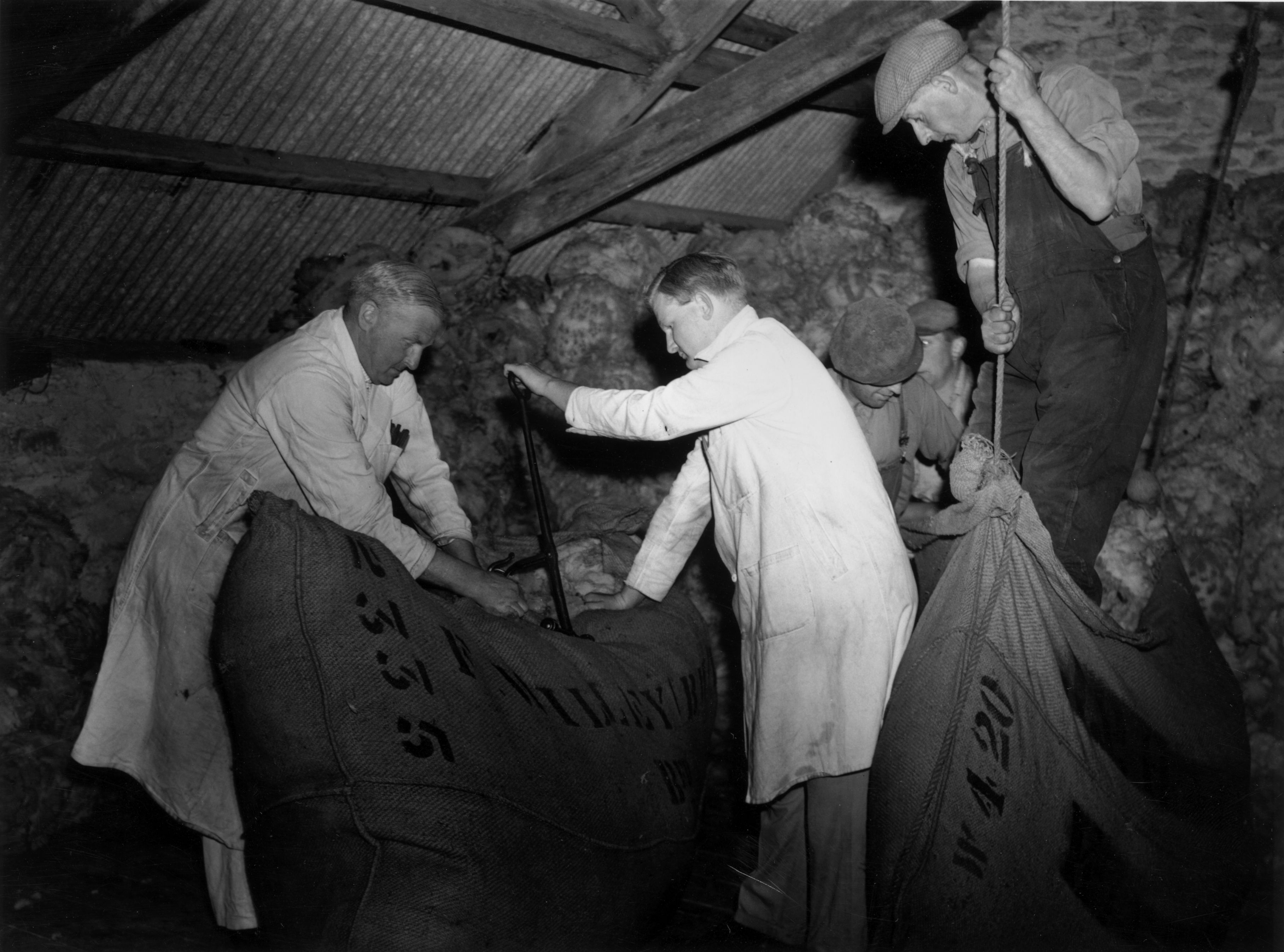

Merchants lacing up a sheet of wool in 1963.

The woolly cost today

Sadly, for many farmers, the price of wool production no longer makes it financially viable. It costs, on average, £1.50 to shear a sheep, and yet the value of said fleece is less than 30p. Some farmers are now composting and burning their fleeces instead, to save money. The British Wool Marketing Board is responsible for selling wool on behalf of British farmers, with its cost being decided through auctions, with different prices for different breeds.

From sheep to sweater is a complex, and hence expensive, process. First, the fleece must be scoured and carded by a wool merchant, then spun by a yarn maker, turned into cloth by a mill owner and knitted by a clothing manufacturer.

‘People are going down the wool shedding route to reduce their costs,’ says Nicola Noble, project manager at the National Sheep Association. ‘On the opposite side of the coin, there are still many very keen pro-wool farmers, who are trying to produce better quality wool.’

The farmer world is split, she says but ‘if British wool disappears — it is the only body that auctions all wool types. If we lose it, we’d be in a predicament, as it offers shearing courses as well — teaching young shearers how to do their jobs.’

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

There is also a consumer barrier, Nicola says. ‘People would rather buy 20 synthetic jumpers at £5 each than pay the equivalent for a wool jumper that would last them a lifetime.’

Are you being fleeced?

The perks of wool products, however, are still numerous, and justify the cost of wool production, in most cases. The uses of wool are many — extending far beyond just horrible jumpers that your mother buys at Christmas. Wool revitalised the duvet game in the 1970s when the Continental quilt came onto the scene, and the material was later championed for its quality bedding uses by Monty Don, when he spoke of its benefits in 2009 on the Channel 4 programme My Dream Farm. This caused its popularity to soar still further, with the company Woolroom being a main player when it came to sales.

The reason wool is so good for bedding is because it is a natural fibre, unlike many synthetic duvets. It offers excellent temperature regulation, and can keep you cosy in the coldest of months and cool in the warmer ones as it traps air and absorbs moisture. It also lasts a really long time, making it ideal for clothing items such as socks, which get a lot of wear, jumpers and coats and it is naturally hypoallergenic and biodegradable. Not to mention, it occurs naturally — one needs only some shears and an agreeable sheep.

Andrew Hogley, the CEO of British Wool, calls it ‘a material for the future’ and says wool is ‘gaining new relevance in a world increasingly concerned with environmental impact’. The role it plays in supporting rural communities and preserving heritage skills, at any rate, makes it well worth its price tag.

British Wool is running events at its depot for the general public in September and October. Visit their website for more information and to book a visit

Lotte is Country Life's digital writer. Before joining in 2025, she was checking commas and writing news headlines for The Times and The Sunday Times as a sub-editor. She has written for The Times, New Statesman, The Fence and Spectator World. She pens Country Life Online's arts and culture interview series, Consuming Passions.