Raising the steaks: Which native animal produces the best beef?

We tasked eight gourmands — including food writer Tom Parker Bowles and chef Jackson Boxer — to find out which native British cow produces the best côte de boeuf.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Jackson Boxer served his first meal at London's Brunswick House in 2010. Back then, his kitchen was still a pop-up and the building better known as a giant antiques market. Today, it is arguably south London’s best-loved restaurant and, as of August 26, something of a satellite location for Country Life.

The full story dates back to June, when several members of the team got together to discuss the fact that British beef was having what’s known as ‘a moment’. The advent of nose-to-tail cooking, first popularised in this country by Fergus Henderson in the mid 1990s and now mimicked everywhere, has dispelled the idea of red meat as a wasteful, cruel or environmentally negligent choice. Pescatarianism — the practice of eating fish, but not meat — has been on the decline, particularly since the ethical and ecological bases for the movement have been called into question by headline-making figures about bycatch. Scientists and nutrition experts have also been keener than ever to stress the importance of a protein-rich diet. Yeotown, a much-loved health and wellness centre in north Devon, recently introduced animal proteins into a diet that had, for years, been vegan. Vegans themselves are becoming fewer and fewer, with the sale of meat alternatives dropping continuously. Consumers have decided, either due to eco-fatigue or in the interest of their own health, that they would rather eat the real deal than an artificial knock-off.

British cattle are some of the best and tastiest in the world, with native breeds ranging from the Highlands of Scotland to the lowlands of Devon. Among the most renowned are the Angus, the Hereford and the Longhorn — the latter’s magnificent, sweeping headgear something out of prehistory. British meat generated £11.3 billion in 2024, a 5.8% increase from the previous year. Although its global reputation may not yet have reached the heights of French or Argentine beef, this may have more to do with perception of British gastronomy than any actual quality control.

As far as our kitchens are concerned, meat from grass-fed British cattle that has been left to age for three to four weeks is almost impossible to beat. Our South American counterparts turn their noses up at this, selling their beef fresh without ageing it, due to the different genetic make-up of their breeds. However, leaving beef to hang is important: it dehydrates the steak, allowing natural enzymes to break down muscle proteins. Also, as we contend with the realities of climate change and the difficulties faced by farmers since the changes in inheritance-tax laws and grant cuts, it is more important than ever to champion ethically reared, home-grown beef rather than rely on imports.

As we weighed up all these considerations, one of us remembered that Country Life had, in the past, hosted a steak tasting. We dug into the archive and found a four-page spread from February 2009, titled ‘Britain’s Best Steak’: supper with the great and good of the culinary arts at Hix Oyster Chop & House, among whom were Mark Hix, Fergus Henderson, Mark Price (then chief executive of Waitrose) and the Countess of Cranbrook (a campaigner for local food). Nine sirloins and nine fillets were served plain, although no doubt with a lot of wine, allowing natural flavours to take centre stage. The winning breed, supplied by Meridian Meats in Lincolnshire, was the Longhorn — which this magazine’s editor crowned ‘the perfect steak’.

We decided the time was ripe to host a fresh tasting, with a new set of judges and an updated list of cattle. After a few telephone calls to the chief executive of the Rare Breeds Survival Trust, Christopher Price, we were under way. Eight different suppliers, each specialising in a different native breed, would deliver a côte de boeuf to Brunswick House, which Jackson would then cook for a select committee on a Tuesday lunchtime, when the restaurant is closed to the general public save for the odd passer-by in search of an old lamp. On August 26, that is exactly what we did.

The meat of the matter

Not all cuts of meat are created equal. The Chateaubriand, prized from the centre-cut of the beef tenderloin, is traditionally viewed as the best. Ribeye, however, is a fan favourite thanks to copious marbling — the intramuscular fat that appears on the raw steak before it goes on the griddle.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Marbling says a lot about how an animal lived and what it ate. Grass-fed cattle tend to come with a leaner and more yellow-hued fat, which yields a more mineral flavour than its grain-finished counterpart. The marbling in corn-fed cattle is typically more abundant and yields a sweeter, buttery flavour. It enhances the beef’s moisture and tenderness when it melts, effectively basting it during cooking.

What we call ribeye is actually a côte de boeuf that has had the bone removed. In this case, Jackson asked that these be delivered on the bone, as cooking them thus preserves the cut’s juiciness and tenderness. The côte de boeuf is a naturally tender cut, as the muscles in the fore rib are less regularly used than others. Finally, the fact that it is close to the heart of the animal — where fat storage reflects diet over time — means it also serves as a key indicator of the animal’s health.

Jackson forbade vacuum-packing as a method of transportation. All meat was instead wrapped in paper and delivered to Brunswick House in the days before the event. ‘Vacuum-packing puts the meat under enormous pressure,’ the chef explains, ‘causing it to marinade in its own juices, which ends up giving a horrible, tangy, metallic flavour.’

The steaks were brushed with rendered beef fat; then cooked over a hot, gas-fired charcoal grill for a couple of minutes on each side and subsequently moved into a slow oven, heated at about 80˚C, where they were left to cook for 20–40 minutes, depending on the thickness of the steak. Once done, the beef was laid to rest for another 10 minutes before being carved and brushed with the remaining juices. Each steak was served medium rare and topped only with sea salt: no sauce, no oil, no garlic, no herbs. Side dishes were chips and garden salad, all watered down with several bottles of Brunswick House red.

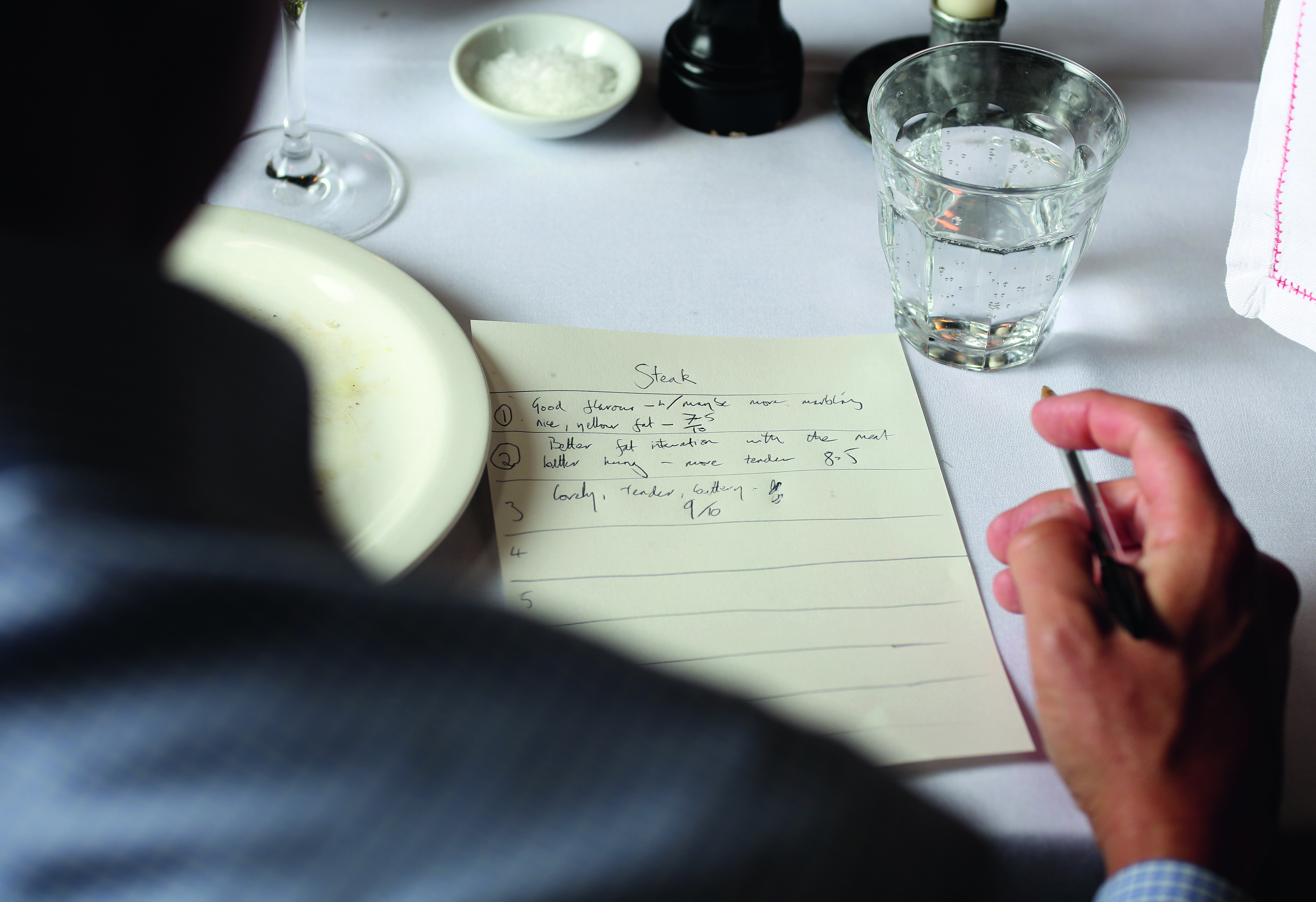

This process was repeated eight times in quick succession, so that each steak could be served warm for the judges and with enough time between plates for them to jot down their thoughts. Each steak was given a score out of 10, which were added up after lunch to give each breed a total mark out of 60. Following a careful tally, the Longhorn proved to be the runner-up. Beating it by only one point was the plucky, adaptable Dexter.

Dexters are the smallest native breed and very hardy, able to live outside all year round and scale hilly, inhospitable terrain — the kind that would normally be accessible only to sheep. Moreover, Dexters can forage for food, being able to digest grass, weeds, leafy plants and even small shrubs.

‘They look after themselves,’ Mark Hedges, Country Life's editor-in-chief explains. ‘They can eat a varied diet and love wildflower meadows.’

Gourmands Diarmuid Goodwin, Tom Parker Bowles and Sam Hart are keen not to miss a morsel of the eight servings.

One wonders how swiftly the judges ran out of superlatives when faced with such succulent steaks — and a few glasses of red.

‘What was interesting about this tasting,’ Jackson considers, ‘is that the consensus was almost unanimously in favour of beef that had been reared on grass and given a really long age.’ These cuts had a rich, dark hue and were beautifully dry when delivered to the kitchen, ultimately yielding more complex and aromatic flavours.

Still, ‘everyone’s taste is different,’ Jackson cautions. ‘A lot of people love younger beef that hasn’t been aged or dried for as long. Even corn-fed beef…’ Margot Henderson, the panel’s harshest scorer, concurs. ‘All these steaks…’ she tells me enthusiastically after lunch. ‘Everyone loved them all!’

Our generous suppliers came from all over the country, each one selected by the patron of the native breed society to which they are affiliated. We cannot thank them enough for taking part in our competition and for giving our judges the feast of a lifetime.

The winner

Dexter

Emerging in the 18th century from south-west Ireland and brought to Britain in 1882, Dexter cattle are the smallest native breed, with cows standing up to 3ft 6in at the shoulder. Yet Dexters are not the obvious small-holder’s cow, as they can be lively to handle — although they are noted for their ability to thrive on rough pasture in cool, damp climates and to forage naturally for food.

‘Juicy, gentle, buttery, exquisite’ — Margot Henderson

Supplier

Making Place Dexter Beef, Halifax, West Yorkshire.

The runner-up

Longhorn

Dating back to 16th-century northern England, Longhorns are easily recognised by their sweeping headgear and are prized for their rich-flavoured beef, as well as their milk, which is so high in butterfat that it was crucial to the success of the Stilton and Red Leicester industries. The breed society says that the longhorn is ‘beyond equal’ as a suckler cow and its longevity and fuss-free calving also make it a desirable cross.

‘Deep and rich flavour; soft texture; caramelised’ — Diarmuid Goodwin

Supplier

Tori & Ben’s Farm Shop, Park Farm, Melbourne, Derbyshire.

And the rest

Aberdeen Angus

Originating in the early 19th century in Aberdeenshire and Angus in Scotland, these cattle are naturally polled and hardy in cold, wet climates. They are prized for their calm temperament and exceptionally marbled beef, giving their meat a rich, juicy flavour. Yet few people realise when eating the ubiquitous ‘Aberdeen Angus’ steak that its connection to the genuine article may be, at best, remote; an animal can be classified Aberdeen Angus when it’s cross-bred and even, in the US, merely if it’s black.

‘Delicious flavour and nice, yellow fat’ — Mark Hedges

Supplier

Farmer Luxton’s, Okehampton, Devon.

Hereford

The Hereford is perhaps the British native that has best stood the test of time. The Herd Book, founded in 1846, has, since 1886, been closed to any animal whose sire and dam had not been recorded, to ensure purity. Due to the breed’s adaptability, healthiness and ability to flourish on a forage-based diet, there are more than five million pedigree Herefords across 50-plus countries.

‘Great fat intonation; serious hanging; gamey depth’ — Sam Hart

Supplier

Farncomb Farm, Hungerford, Berkshire.

Shorthorn

Bred in the late 18th century in north-east England, the Shorthorn was one of the first dual-purpose breeds valued for both milk and meat — which, in the 20th century, caused it to split into two strains, dairy and beef. The two now have their own societies. Shorthorns are also genetically important cattle, which have been used worldwide in the development of more than 40 breeds. They are known for their adaptability, gentle nature and success in temperate climates.

‘Tastes of a life well lived’ — Tom Parker Bowles

Supplier

Treway Farm, Coombe, Cornwall.

British White

With roots in Lancashire and East Anglia, British Whites are hardy, naturally polled cattle, prized for their striking white coats with sooty points, simple calving and calm, manageable temperament. They do well in cool and wet conditions and are descended from ancient, indigenous animals, their preservation a tribute to careful management by single, large estates such as The King’s at Highgrove, Gloucestershire.

‘Great ageing, complexity and marbling’ — Jackson Boxer

Supplier

The Newt, Bruton, Somerset.

Welsh Black

An ancient breed dating back more than 1,000 years in Wales, Welsh Blacks are tough and adaptable to wet and mountainous environments. They were once so valuable that they were known as ‘the black gold from the Welsh hills’ and the cows are admired for their strong maternal instincts. Until the 1970s, the Welsh Black tended to divide into the stocky beef cattle of North Wales and the dairy cattle of South Wales, but the modern animal is dual purpose.

‘Delicious, grassy flavour’ — Diarmuid Goodwin

Supplier

Nixon Farms, Buith Wells, Powys.

Devon

The county of Devon boasts cattle to match its rich, red soil. Francis Quartley, an 18th-century Exmoor farmer, can take much credit for today’s healthy herd. As other farmers rushed to sell cattle for high prices to feed troops in the Napoleonic Wars, he refused to part with his; the herd lives on at the same farm at Great Champson, Molland. The breed is known for its strength as a draught animal, performing well in both upland and lowland conditions and yielding noticeably lean beef.

‘Well rounded with soft, luxuriant textures’ — Jackson Boxer

Supplier

Native Beef, Rickmansworth, Hertfordshire.

Meet the judges

Jackson Boxer is the award-winning chef-proprietor of Below Stone Nest, Dove, and Brunswick House. He is also executive chef at Cowley Manor, Gloucestershire, The Corner at Selfridge’s, and Henri at Henrietta Experimental. Jackson read English at Cambridge before opening his first restaurant at the tender age of 24, having previously baby-sat the children of gastronomical royalty, Fergus and Margot Henderson. He contributes to the Financial Times.

Mark Hedges has been editor-in-chief of Country Life since 2006. Growing up in the Cotswolds, where his father kept suckler cattle, he has lived in Hampshire for several decades and helped launch Hampshire Cheeses, which has twice won Supreme Champion at the British Cheese Awards. Before entering publishing, he worked as a gold prospector. He is now just shy of his 1,000th Country Life issue — which, in his own words, is ‘rather a lot of lunches’

Diarmuid Goodwin is a chef from Belfast, Northern Ireland. He worked for seven years with Angela Hartnett, eventually becoming sous chef at Cafe Murano and later became senior sous chef at Trullo, N1. He then headed up the kitchen at Sager + Wilde, where he became fluent in the culinary traditions of the Basque Country and Provence. He currently hosts pop-ups and residencies across London and Belfast.

Margot Henderson is an award-winning chef from New Zealand. She opened the dining room at The French House, London with her husband, Fergus, in 1992. The two met one Sunday afternoon at The Eagle, where she was working at the time. In partnership with Melanie Arnold, she founded a catering business, Arnold & Henderson, working with clients such as Zaha Hadid, the Gagosian Gallery and Alexander McQueen. In 2004, they opened Rochelle Canteen together in the bicycle sheds of an old Victorian school, where Margot remains chef-patron to this day.

Sam Hart is the CEO of Harts Group, a collection of hospitality brands that includes Barrafina, Quo Vadis and El Pastor. Many of these are inspired by Sam's time in Mexico, where he lived for five years. In 2018, Harts Group won Opening of the Year at the industry R200 awards for the launch of Drop at Coal Drops Yard.

Tom Parker Bowles is an award-winning food writer and the author of nine cookbooks, including E is for Eating: An Alphabet of Greed and The Year of Eating Dangerously. He is a contributor to Country Life, The Mail On Sunday and Tatler and brought an unannounced guest of honour to the steak tasting: his Jack Russell, Maud (below).

Will Hosie is Country Life's Lifestyle Editor and a contributor to A Rabbit's Foot and Semaine. He also edits the Substack @gauchemagazine. He not so secretly thinks Stanely Tucci should've won an Oscar for his role in The Devil Wears Prada.