In Focus: The Palladian folly that was the scene of Veere Grenney's splendid isolation

What did the legendary interior designer Veere Grenney learn from spending lockdown in a Palladian folly? Giles Kime finds out. Photographs by Simon Brown. living

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Veere Grenney is no stranger to the departure lounge. As well as homes in London and the countryside, he has a third in Tangier and clients all over the world. But, in 2020, Covid brought the merry-go-round to an abrupt halt and he retreated to the fishing lodge-cum-folly he has rented for the past 30 years near Stoke-by-Nayland on the borders of Suffolk and Essex. It was built in the 1760s by Robert Taylor in parkland at the now demolished Tendring Hall and more recently it was the weekend home of the interior designer David Hicks.

Not only was Mr Grenney’s diary suddenly devoid of relentless travel, but like the rest of us, things he took for granted vanished overnight: friends, parties and the stimulation of the outside world. His permanent presence at the Temple, as it has become known, with only his lurcher, Rio, for company, threw his beloved bolthole into forensic focus.

The building is best described as pocket Palladian; in addition to a beautiful drawing room, with views over a tree-lined canal, are a bedroom and small kitchen, a dining table and little else. There are few concessions to the 21st century: no dishwasher, washing machine and at the beginning of lockdown the television stopped working. ‘I rediscovered the joys of domesticity. Cleaning, cooking meals every day and doing laundry by hand changed my relationship with the Temple and I saw it in a rather different light,’ he says of that spring and summer of 2020.

It became much more of a hard-working home, ‘previously it had been a weekend retreat, where I spent holidays with my parents and my niece was married.’ For those few months the Temple and surrounding parkland became his home, office and the limits of his world.

Mr Grenney’s prolonged stay demonstrated that comfort is a complex concept. ‘People assume it’s all about upholstery. Well, of course it is, but that’s a given,’ he says. There are so many other factors that also need to be addressed and spaces need to be humanised. ‘The scale of Palladian proportions can be quite intimidating,’ he says. The answer, he says, lies in balancing and humanising the scale with a coherent arrangement of furniture that directly addresses the needs of the occupants. ‘More important than anything,’ he says ‘is balancing the geometry of the space.’

At the Temple — as it is in all Mr Grenney’s work — achieving perfect geometry is as much about the contents and decoration of a room as the architecture of the building. Colour schemes and curtain treatments are startlingly simple, giving the drawing room a look that is, if not contemporary, then certainly timeless, a talent he honed early in his career when he worked with two masters of the art, Mary Fox Linton and David Hicks. It was an apprenticeship that, when combined with the time he spent as a director at Sibyl Colefax and John Fowler, allowed him to develop the knowledge, experience and confidence that have made him one of the most sought after interior designers of his generation.

‘Combining comfort and style,’ he says, ‘are about so much more than pictures on Instagram.’ Having arrived in London overland from New Zealand in the 1970s, he doubtless also knows a thing or two about discomfort. But it is also the sort of experience that gives a designer a broad frame of reference.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

In many cases, he says that the foundations of a pleasing environment are many, varied and about more than simply the way things look. ‘People underestimate the importance of all the senses when creating a great space.’ As an example, he mentions that each day, the ebony floorboards at his house in Tangier are washed with water scented with rosewater. Where comfort is concerned, it seems that the little things go a long way.

The long months of 2020 also reminded Mr Grenney of so many of the other pleasing characteristics that drew him to the Temple in the first place; the views over the rectangular stretch of water and west over farmland, the beautiful light and the shallow stairs that provide an effortless ascent from the kitchen to the drawing room above.

Back in the office, in the homes of his clients and in Tangier — where, this summer, he hosted a one night performance of Stephen Sondheim’s Follies — his exile has reinforced his view that where comfort is concerned, the whole is far greater than the sum of its imperceptible parts.

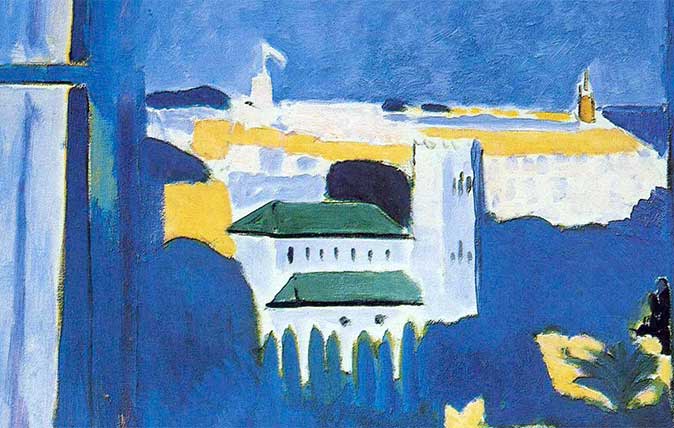

My favourite painting: Veere Grenney

'In his Moroccan series, which I love, he captures the light, colour and exoticism of North Africa.'

Credit: Hasselblad H3D

The benefits of four-poster beds: 'I’ve never met anyone who doesn’t sleep better in one'

Interior designer Veere Grenney tells Arabella Youens why the only bed to have is a four-poster.

Why you should avoid matching and use colours and patterns to bring a living room to life

A cold, damp week in August? Then it's time to reach for the sherry, Port or Madeira

When it's pouring with rain and the damp chills you to the bone, forget what month the calendar says — just