'Each of my active ancestors had the good sense and taste to purchase or commission the outstanding work of their time': Meet the collecting dynasties

Whether it is adding contemporary paintings to a gallery of Old Masters or branching out into territories as diverse as Modernist chairs, Iranian tiles or Churchill memorabilia, the passion for collecting seems to run in some families.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

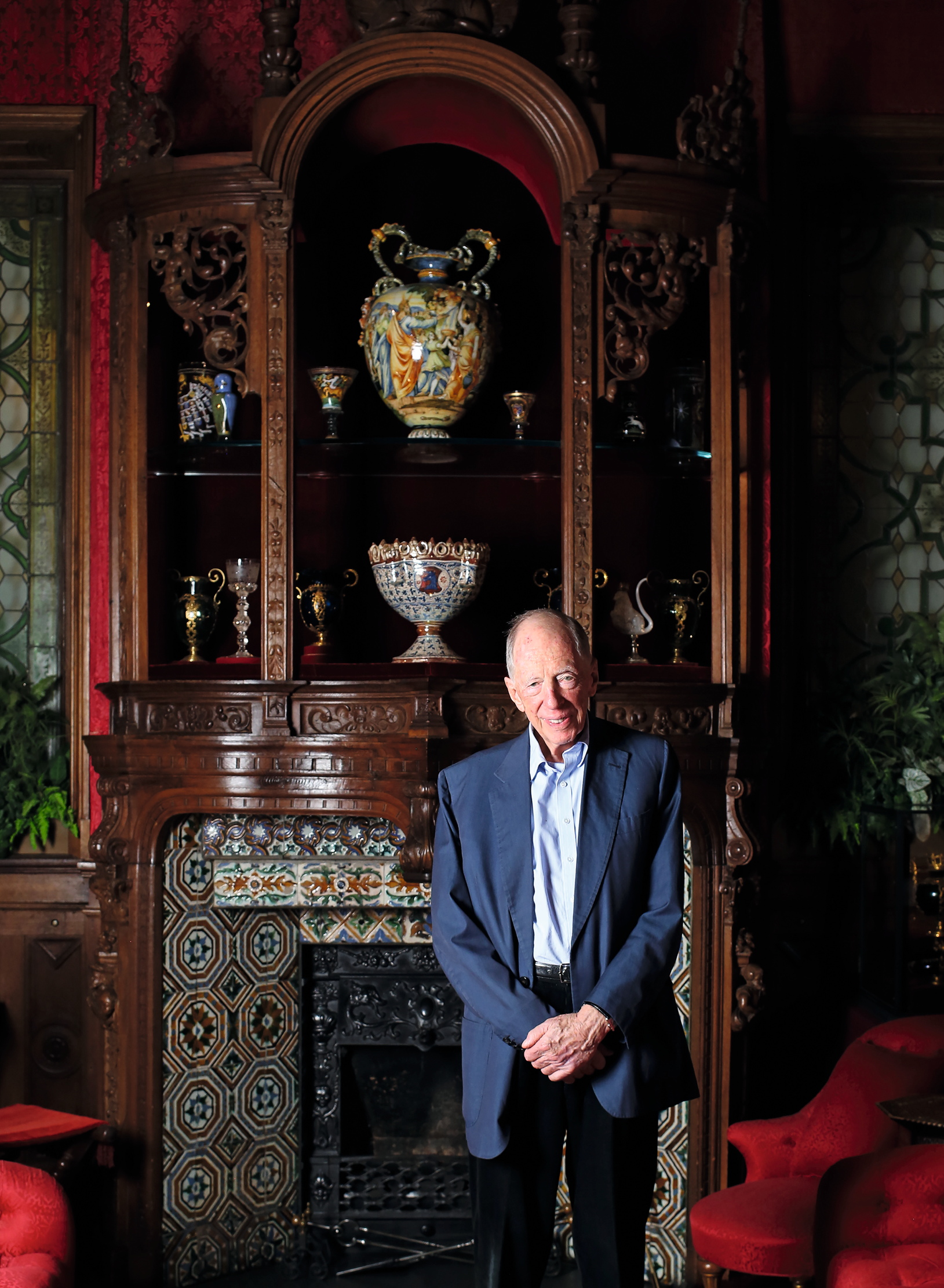

When the late Jacob Rothschild, 4th Baron Rothschild, was nine, his grandmother Mary Hutchinson, a cousin of Lytton Strachey, gave him a painting of a hummingbird by the French artist Simon Bussy.

The artist was a friend of Henri Matisse; he had, in 1903, come to England and married Dorothy Strachey, a cousin of Lord Rothschild. That first painting ignited in the late Lord Rothschild the collecting bug. By the time we met in 2023 at Eythrope — his house near Waddesdon Manor, in Buckinghamshire, completed in 1883 by the ‘maniacal collector’ Ferdinand de Rothschild — he had 60 works by Bussy.

‘I have been captured like a magpie, as a collector,’ Lord Rothschild told me at the time. ‘I am half Bloomsbury and half Rothschild and it has always been all around me on both sides of my family with different types of collectors — art lovers, building lovers. It was encouraged.’

'On October 29, 1963, in the middle of a game of bezique, Lady Juliet snaffled half a Churchillian cigar into her handbag'

Jacob Rothschild was 'captured like a magpie, as a collector'.

This can happen in families in which there is, you might say, a collecting gene — out of which often springs a long collecting dynasty, as attested by those country houses, from Chatsworth, Derbyshire, to Powderham, Devon, in which the treasures gathered over the generations continue to be harboured.

Not all have stayed faithful, of course. In 1886, George Spencer-Churchill, 8th Duke of Marlborough, offloaded more than 200 paintings from the collection at Blenheim Palace, Oxfordshire. The sales provoked a great deal of sadness within the family; his younger brother Lord Randolph Churchill remembered how, when travelling in Europe, he kept finding works from Blenheim in other people’s houses — in 1888, staying with Sir Edward and Lady Ermytrude Malet at the British Embassy in Berlin, he observed three pictures from his ancestral home gracing their gallery.

Others, however, have built on the foundations laid by their predecessors. After the Second World War, Henry Thynne, 6th Marquess of Bath, began to consider how he could advance the collection at Longleat, in Wiltshire. ‘Each of my active ancestors had the good sense and taste to purchase or commission the outstanding work of their time,’ he once recalled. ‘I felt it was incumbent on me to follow the same pattern.’

Thus, rather than going to Sotheby’s and ‘bidding for another Titian’, he thought he would gather items associated with the great men of his own age. He set about collecting Churchill memorabilia — beginning with books and racing colours that belonged to the former prime minister and branching out, in 1963, into his cigar butts.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

That year, he received in the post a cigar from Churchill. After he had it framed, he discovered that it was not one of the favoured smokes, but an inferior model, which left him unsated and led him to ask his cousin Lady Juliet Duff to help him acquire a proper one. She duly obliged: on October 29, 1963, in the middle of a game of bezique, Lady Juliet snaffled half a Churchillian cigar into her handbag.

There remain plenty of similar stately collectors — albeit of more conventional goods. At Althorp in Northamptonshire, the picture gallery displays van Dyck and Sir Peter Lely, together with Britannia by Mitch Griffiths, a contemporary artwork representing the state of modern Britain and one of the pieces that Charles, 9th Earl Spencer, has added to his collection.

'If you had lain on the stairs at Drumlanrig Castle, you would be in the "only place in the world where you can see simultaneously a Rembrandt, a Holbein and a Leonardo da Vinci'"

The Duke of Buccleuch (right) and Kim Wilkie admire Orpheus, in the grounds of the Boughton Estate.

Seven miles away at Boughton, Richard Montagu Douglas Scott, 10th Duke of Buccleuch, has enhanced his family’s extraordinary collection — one so great that, once, as his father said, if you had lain on the stairs at Drumlanrig Castle, you would be in the ‘only place in the world where you can see simultaneously a Rembrandt, a Holbein and a Leonardo da Vinci’ — with Orpheus, a monumental example of land art by Kim Wilkie.

As a child, Christie’s chairman Orlando Rock would watch as piece after piece of country-house furniture was loaded into his father Tim Rock’s Volvo. ‘He had a terrible collecting bug,’ recalls Orlando. ‘My wife, Miranda, is terrified I have the same disease.’ The elder Rock was, his son explains, ‘obsessed with the architecture of English houses. Because a lot of big country houses had been broken up and all of these great things were cropping everywhere, he found it irresistible to bring something home — much to my mother’s despair.’

Today, in his professional life, Orlando sees scores of collectors at the top end of the market, those not only with unlimited funds, but with ‘incredible focus and discipline’. His approach differs. ‘I am much more of a Horace Walpole type of collector. I have no discipline. I am as interested in the people who owned things in the past as in the objects. There is an incredible romance with something that might have been worn by Charles I at his execution — that’s something I find very evocative.’ Orlando’s collecting is not linked to a specific area, but derives from a wide range of obsessions. ‘I have tile-mania at the moment,’ he confesses. ‘I’m mad on early Iranian tiles. I spend my life buying them and working out where I am going to put them.’

'I’m mad on early Iranian tiles. I spend my life buying them and working out where I am going to put them'

What makes his collecting all the more marvellous is that its backdrop is Burghley House, Lincolnshire, which for the past 500 years has been home to his wife’s family. ‘Because I know the collections at Burghley pretty well,’ he explains, ‘I spend my life buying things that Miranda’s ancestors would have appreciated.’

The Japanese lacquer he so loves is a passion shared with ‘the Travelling Earl’, John Cecil, 5th Earl of Exeter, who died in 1700. ‘I can’t resist a piece of 17th-century lacquer. That’s the joy of collecting things, objects that speak through the centuries.’ Another of his weaknesses is for hard stones and marbles — ‘a 9th Earl of Exeter passion’. His wife’s forebears simply bought things that they felt passionately about: ‘I don’t have the depth of purchasing power that they had, but they bought things because they loved them — some were valuable and some were not.’

As did Orlando, Swiss artist Rolf Sachs grew up with interesting pieces all around him. His father, Gunter Sachs, a German industrialist and photographer, started acquiring them after the war ‘in a time when basically nobody was collecting. He moved to Paris in 1958 and was very influenced by the Paris art scene’. One of the famous galleries of the time was run by Jean-Marie Rossi and bursting into life were nouveau réalisme artists, including Yves Klein, Jean Tinguely or Daniel Spoerri.

Spoons, chairs, scarves — Rolf Sachs collects them all.

However, the market was ‘very insular,’ notes Rolf. ‘Father was also interested in the Pop Art movement and embraced it. He started a gallery in Hamburg called Gallery Gunter Sachs.’ In 1972, Sachs Snr held the first Andy Warhol exhibition in Germany. ‘The Hamburg bourgeoise came and he didn’t sell one picture — he was highly embarrassed!’ It turned out to be for the best: the Warhols were an extremely good investment, ‘although he didn’t buy art for investment. It was just something he liked — he was an aesthete,’ says Rolf. His father’s broad collection continued to be filled — with works by Pablo Picasso and René Magritte, as well as Max Ernst — but then, he got out. ‘He stopped collecting when the art market really started happening and became, in his eyes, too commercial,’ reveals Rolf. ‘At the end of the 1970s, there was a boom and he lost interest.’

By then, however, the passion had already rubbed off on his son, who has been collecting since he was a child — ‘cigar boxes in the beginning, stones. If you have a collector’s bug, it is somehow in you’. He has bought art, but ‘not as broadly as my father, because I couldn’t afford it’. He likes what he calls ‘artists’ artists’ — those that are ‘groundbreaking or have a new intellectual idea. I often buy a small one by someone, because I want to buy the idea. It might be a painting by [Kazimir] Malevich, but a small one, or one by his pupil, because it brings me satisfaction’. He particularly likes the Austrian artist Martha Jungwirth and if he could, would buy work by the late Joan Mitchell: ‘I am not that much attracted to Jackson Pollock, but Joan Mitchell I find super interesting.’

'If you come into a restaurant, the style is defined by the chair. It’s an interesting, highly complicated object'

More than art, however, he is known for his design collection: he has in the region of 200 chairs. ‘People complain that I have sitting rooms where you can’t sit anywhere because things are made of metal and they’re cold and hard.’ The most comfortable of his numerous seats, he laughs, is probably by Frank Gehry, ‘a cardboard chair — people are worried about breaking it’.

This collection began with the avant-garde designers, ‘and then I started buying from the Modernists — intellectually, it’s an interesting art-historical chapter’. Chairs are both vital and style defining, he believes. ‘If you come into a restaurant, the style is defined by the chair. It’s an interesting, highly complicated object.’

Yet, he has an even better-known collection: scarves. He has about 200 of these, too. ‘As an artist, you have a sensibility in how you dress, so I always wore a scarf, and now, if people see me without one they say, “where’s your scarf?” ’ He lives between London, St Moritz and Rome. ‘I am stuck with scarves,’ he laughs, ‘even in Rome, where it’s so hot.’