'There were no fireworks. The art world remained unshaken. Then, this April, a letter arrived... to see it hanging in Tate will be very special': Art dealer John Martin on the piece he'd never part with

A chance encounter with a huge, shimmering panel led art dealer John Martin to discover Nigerian sculptor Asiru Olatunde, a man who also owed his artistic career to an accidental find, as Carla Passino learns.

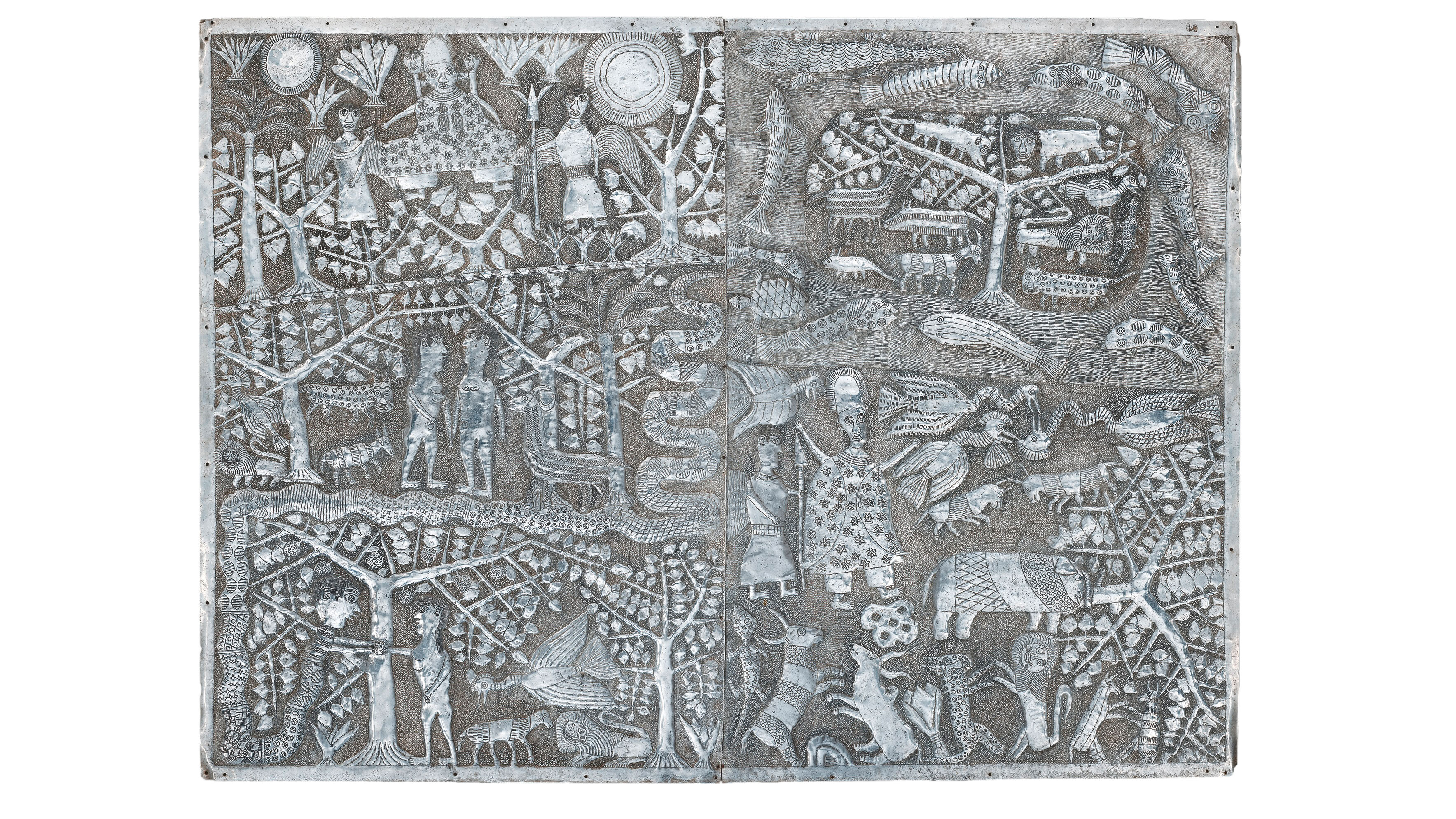

Love strikes unexpectedly. For art dealer John Martin, it happened at a west London auction 20 years ago. There, tucked incongruously among tribal art and collectables, was an extraordinary panel, ‘a huge, shimmering depiction of the Garden of Eden, its story picked out on aluminium sheets with thousands of tiny punch marks’. God, dressed as an African king, sat enthroned, flanked by angels; animals grazed peacefully in Paradise — but the Serpent rose up to tempt Eve, leading, in the next scene, to the Expulsion, with an elephant flattening a tree and the beginning of the eternal cycle of hunter and hunted. Mr Martin was smitten—and bought it.

‘At the time, I knew nothing of its maker, Asiru Olatunde, a Nigerian blacksmith of the Oshogbo school of artists that emerged in the 1960s, nor of the remarkable Ulli Beier, who had once owned the panel,’ he explains. ‘Beier was a scholar, editor and catalyst, instrumental in nurturing the community of artists and writers who gathered at the Mbari Club.’

The club, thought to have been christened by a young Chinua Achebe, had burst onto Africa’s creative scene in July 1961. It regularly held exhibitions, published the work of emerging writers and, for a minimal fee, gave members access to operas, plays, lectures and art courses.

One day in 1961, an accidental find brought Asiru, born in Osogbo in 1918, into the club and the burgeoning Nigerian art scene. Stepping outside his house, Beier chanced upon a small copper earring. It had been made by Asiru, who had initially set out to take up the family’s smithing trade, but had moved into jewellery-making after falling ill.

"To discover an artist as wholly original as [him] and to stumble into the pulsating art world of 1960s Osogbo is the kind of thing art dealers dream of."

By the time Beier found the earring, however, he had been struggling to compete with industrial imports and, saddled with debt, had all but given up. Beier encouraged him to resume his craft and helped him sell his wares to the circle of people that orbited around the University of Ibadan. However, that market was limited, so Asiru began shaping animal figurines — until a suggestion by artist Susanne Wenger led to him working their bodies in relief: ‘Asiru then produced a cow in whose belly a leopard was seen struggling with a lion and an elephant whose bulky body served as background for a Yoruba chief accompanied by his dog,’ recalled Beier in his Contemporary art in Africa. ‘These could be called his first characteristic works and from then on development was rapid.’

To help the sculptor’s artistic evolution, Beier generously bought all his works for almost two years. ‘The temporary strain on my purse paid wonderful dividends in artistic terms,’ he wrote. Working in copper and later adding aluminium, Asiru made panels that told Yoruba folk tales or, despite being a Muslim, stories from the Bible, such as The Garden of Eden.

Mr Martin, as thrilled by the Nigerian sculptor’s work as Beier had been decades earlier, thought he should be better known. Although Asiru had died by the time Mr Martin came across his panel, Beier was still alive and living in Australia. With his help ‘and a few favours called in’, Mr Martin managed to mount an Asiru exhibition in 2005. ‘To discover an artist as wholly original as [him] and to stumble into the pulsating art world of 1960s Osogbo is the kind of thing art dealers dream of.’

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

As it turns out, however, it was not what the public dreamed of at the time. ‘Sadly, there were no fireworks. The art world remained unshaken,’ Mr Martin recollects. ‘And then, this April, a letter: a curator at Tate Modern, planning a show on Nigerian Modernism. Could they borrow The Garden of Eden? So, we got there in the end. That’s why I couldn’t possibly sell the panel — and to see it hanging in Tate this autumn will be very special indeed.’

‘Nigerian Modernism’ is at Tate Modern, London SE1, October 8–May 10, 2026. The next exhibition at the John Martin gallery, London W1, is ‘The Deserted Garden, New Paintings by John Caple’, October 9–November 1 .

Carla must be the only Italian that finds the English weather more congenial than her native country’s sunshine. An antique herself, she became Country Life’s Arts & Antiques editor in 2023 having previously covered, as a freelance journalist, heritage, conservation, history and property stories, for which she won a couple of awards. Her musical taste has never evolved past Puccini and she spends most of her time immersed in any century before the 20th.