The art of the sunrise and sunset: How the greats have captured Nature's finest display

A truly spectacular sunrise or sunset is one of Nature’s greatest achievements. Jay Griffiths explores our timeless desire to capture them in words, music and paint.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

That the sun will rise: this is the most predictable thing we know on Earth. The timings, angles and degrees of its course have an utter precision and the sun, unlike humans, cannot misfit its time or place as it runs in unswerving service to the offices of its hours.

And yet the occasions of its rising or setting – affected particularly by cloud formations – are unpredictable. A splendour of wildness writes its signature across the skies; it eclipses its own strictures into a world of sheer imagination.

Twice a day, we all become pre-Copernican. The sun ‘rises’ and ‘goes down’ we say, as if language refuses to relinquish the intense experience of the senses and we cannot believe it is otherwise. In the unfurling moments of daybreak or dusk, the senses are extra-sensitive and artists, poets and musicians seem compelled to respond.

In what A. E. Housman called the ‘valiant air of dawn’, the sky becomes a painting; rose is both colour and verb.

Day breathes in. Colour surges forward – lilac, crimson, orange and tawny – and sunrise is as eager as the opening radiance of a daisy, whose name comes from the sun, the ‘day’s eye’.

Painting depicts sunrise or sunset, restoring it to sight with diligent brilliance. William Ascroft, painter of sunsets in the 1880s, suggested an almost secretarial role, saying he ‘could only secure in a kind of chromatic shorthand the heart of the effect’.

If painting describes, then literature must translate it from light to word, from colour to thought. However, music, perhaps beyond any other art, must re-create its soul-meaning right in the heart of the listener; the composer must play creator.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Haydn’s Sunrise string quartet (1796–7), although not consciously intended to allude to dawn, earns its appellation from the quickening, ascending phrases growing in voice, variation and volume, as the very word ‘crescendo’ is from crescere, to grow. The music opens sky-wide and yet is as intimate as a garden, all life wakening to warmth, and suggests everything that the sun shines on: the creation, indeed.

https://youtu.be/biyy2tzMb8M?t=8s

In Nielsen’s Helios Overture (1903), the music describes the sun itself, how, out of darkness, it swings up – clear, singular and pure – a huge gong of gold.

Elsewhere, in Grieg’s Morning Mood, the music shows the sunrise within the human spirit, the peerless, daybright melody glinting like sun on water as Peer Gynt is in the sunrise of his life, the happy-go-lucky folk-tale hero setting out into his own dawn.

https://youtu.be/wCEzh3MwILY?t=3s

Both immense in size and ephemeral in time, part of the appeal of sunrise or sunset is its very transience – the work of artists is to trace its vanishing resplendence as it races across a fugitive sky.

In Monet’s work, this fleetingness hints of loss, a sadness for a world always on the point of disappearing. In many of his pictures, even Le Soleil Levant, even as he tried to paint the rising orange sun his eyes were drawn ineluctably to the blues. As Robert Frost wrote: ‘So dawn goes down to day. Nothing gold can stay.’

The crimson-and-yellow sunset of San Giorgio Maggiore at Dusk accorded Monet one gasp of rapture – colour, he said, was his ‘obsession, joy and torment’ – that could never last: the possibility of light is barred by the fact of dark.

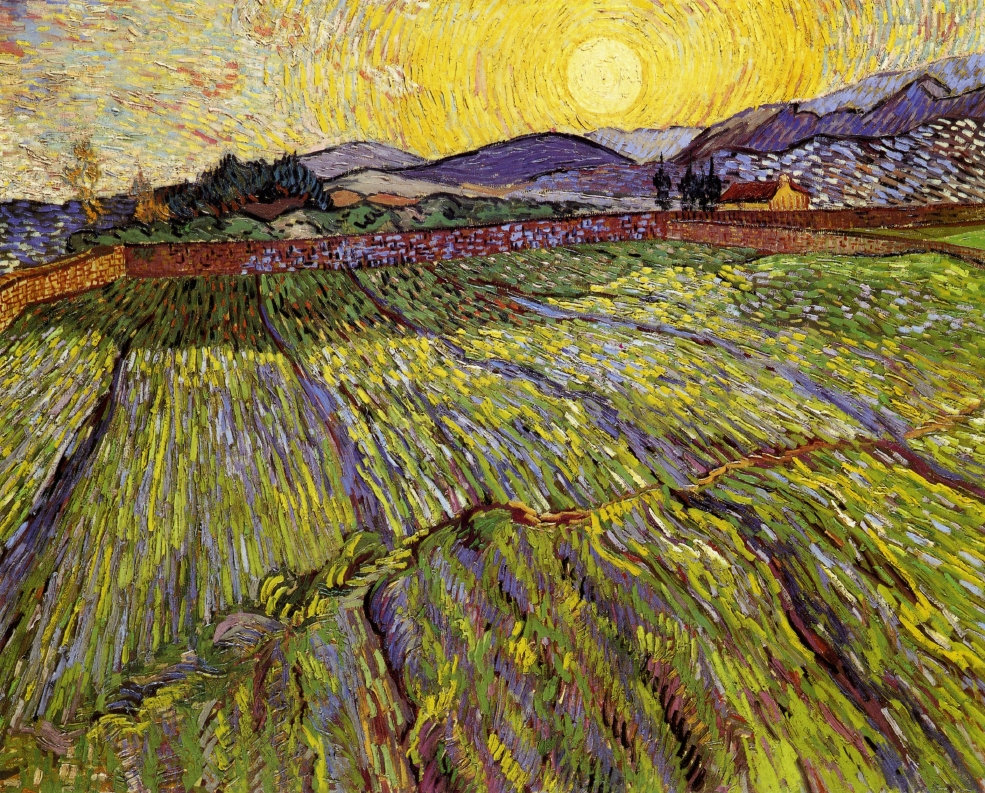

Vincent van Gogh painted sunrise as if the sun, like himself, was anguished by its own energy: Enclosed Field with Rising Sun (1889) suggests what it might be like to be that sun, each pulse of energy perfect, necessary and potentially fatal.

Every scrap of sunlight speaks in a streak of flaming language, as if van Gogh can’t help but hear the ‘instress’, as his contemporary the poet Gerard Manley Hopkins termed it – the impulse that carries the exact impression of a particular thing.

Van Gogh painted as if he were the yellow and the gold: in Sower with the Setting Sun, the huge sun cradles the hand of the sower in its generous arc and both are comprehended by the painter, hand-rounded in reckless empathy.

Would it be true to say that composers, in their creations, favour sunrise and artists, desperate to depict it before it fades, tend to favour sunset? Perhaps the visual dexterity of colour and its generally greater complexity at sunset offers a greater depth to a painter’s eye. Few of them achieve its complex representation as J. M. W. Turner did, letting light stream like liquid thought, each colour lustrous and backlit by an intensity of gold.

In Sun Setting Over a Lake (1840), gold seems more than a paint – it seems to become the precious metal. The Lake, Petworth: Sunset, a Stag Drinking (1829) rings out a peal of bells for its world of sky, lake, trees and swans, which can become once more – for just one gilded moment – the Age of Gold. Turner produced those sunsets. Those sunsets also produced Turner – but why those ones?

In 1815, Mount Tambora in Indonesia erupted, casting fragments into the atmosphere and causing spectacular sunsets for some years across the world. This volcanic eruption intensified the very subject of Turner’s work: light and colour itself. The ash caused dark days across Europe as Byron’s poem Darkness attests and created the Year Without a Summer of 1816, which, in turn, caused widespread crop failure and starvation. Only in 1819 were there good harvests again and a true warmth in the sun, which Keats evoked in Ode to Autumn, written in that year.

The eruption of Krakatoa in 1883 caused sunsets that were almost apocalyptic, with ‘clouds like blood and tongues of fire’, wrote Edvard Munch. The eruption made the loudest sound ever recorded on Earth, heard across almost a tenth of the planet. ‘I felt a great, unending scream piercing through nature,’ Munch continued – he made that howling dissonance visible in The Scream.

Ascroft, meanwhile, painted the sunsets over Chelsea in the years after Krakatoa as if in astounded disbelief at the sky-theatre – more than 500 of his paintings were exhibited as a meteorological record at the Science Museum. Those sunsets were also meticulously observed in a series of articles by Manley Hopkins, poetry in prose, noting the mallow, lilac and sand, the ‘livid green’ and ‘frowning brown’. They were published in the science journal Nature and were, together with a few minor poems, the only work he had published before his death.

Sunset is, in Old English, sunnansetlgong, suggesting the going down of the sun that settles itself into evening. ‘It is a beauteous evening, calm and free,’ wrote Wordsworth. And the day breathes out. The sunset settles birds, colours, children and flowers; the daisy closes with the setting sun, the glorious little commoner rhyming itself – from its yellow centre and petal-rays of light – with the cosmic divinity of the sun.

In the sunset of his own life, Turner’s last words were said to be: ‘The Sun is God.’ Walt Whitman wrote of sunset as ‘corroborating forever the triumph of things’. Sunset can elicit a depth-charge of soul-values, the cadence of evening harmonies, a softening decrescendo – a quieted credo of tranquillity.

Constable ‘added rainbow after his masterpiece first went on display’

The £500,000 house that comes with a £1 million painting... if you can find it

Sotheby’s set new London auction record with £48m Klimt leading the way

A sale of Impressionist, Modern and Surrealist paintings at Sotheby's on Wednesday night set the record for an auction staged

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by His Majesty The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.