An unfenced existence: Philip Larkin's love of the countryside

Richard Barnett pokes at Larkin’s protective carapace of soot-stained gloom and finds a writer with an unillusioned yet tenderly perceptive sense of Nature, in all its beauty and indifference

'Spring never fails us, does it?’, Philip Larkin wrote to his mother in 1954. ‘How beautiful it is, even though it isn’t spring for us!’ One might expect these gentle, honest words from a minor character in a Barbara Pym novel, but hardly from the Larkin of popular consciousness — the great suburban Eeyore of 20th-century verse, the bard of intrays and radiograms and rented rooms in shabby terraces.

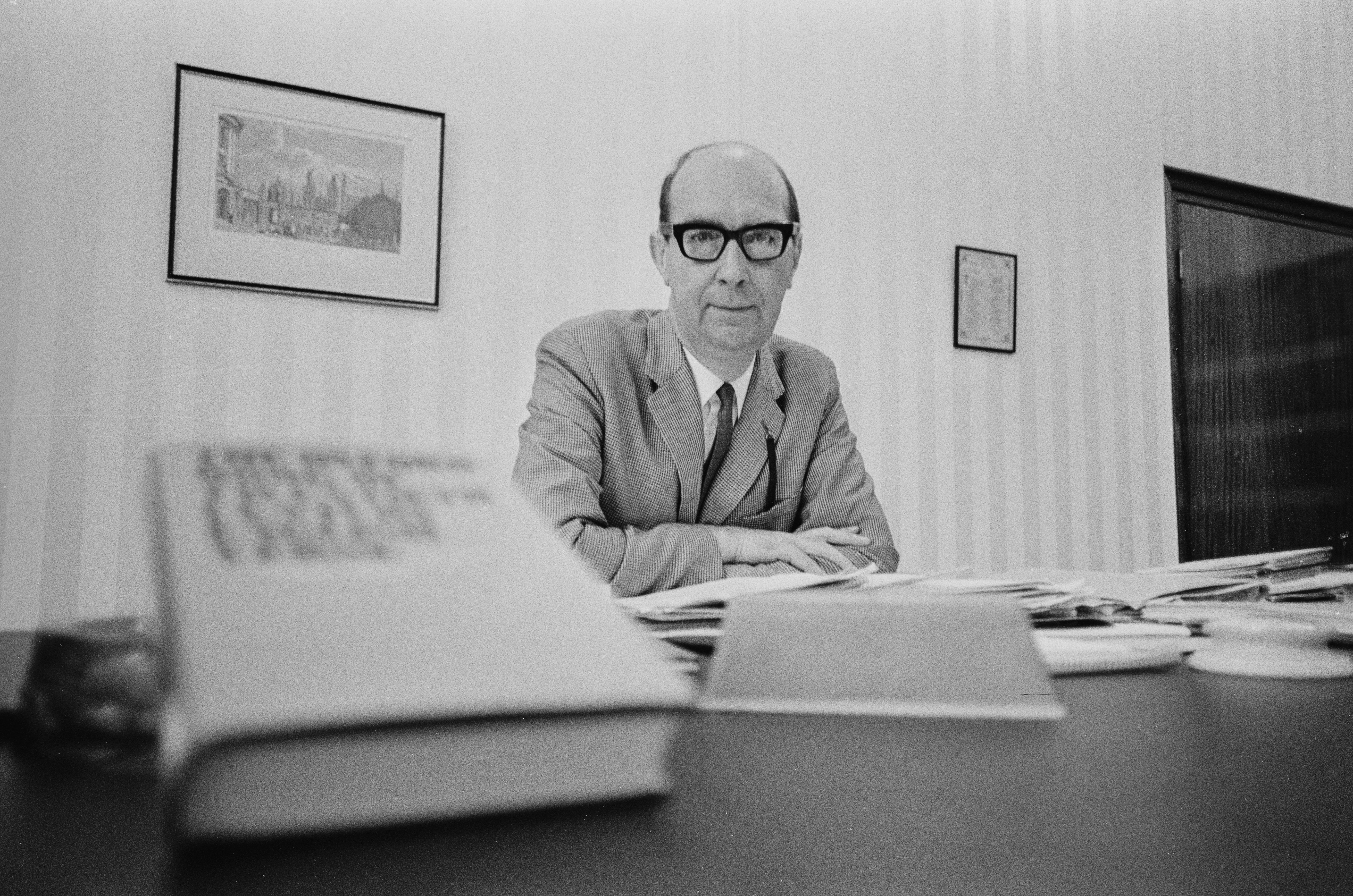

During his life, Larkin was well aware of (indeed, played up to) his reputation for being, as he put it in a 1964 BBC interview with John Betjeman, ‘a miserable sort of fellow writing a kind of Welfare State sub-poetry’. With this year marking the 40th anniversary of his death in December 1985, it’s a fitting moment to poke a little at Larkin’s protective carapace of soot-stained gloom. Beneath it we find, among other things, a writer with an unillusioned yet tenderly perceptive sense of nature, in all its beauty and indifference.

From the opening lines of his first poetry collection, 1945’s The North Ship, to the last page of his final one, 1974’s High Windows, Larkin’s poetry teems with wild settings, images and — especially — creatures, balanced against the all-too-human calendar of appointments and disappointments. The ‘uncaring/ Intricate rented world’ of Aubade, his late-life howl against mortality, is framed and pulled into focus by the ‘unfenced existence:/ Facing the sun, untalkative, out of reach’ that concludes Here, a gorgeously symphonic portrait of the Humber estuary.

Think of Larkin and most of us think of two industriously unromantic English cities, Coventry and Hull. Born in the former in 1922, he went up to St John’s, Oxford, in 1940 to read English. After an unexpected First (and two long-underrated novels, Jill and A Girl in Winter), Larkin’s career traced out a gazetteer of provincial life, with librarianships in Shropshire and Leicester in the late 1940s, Belfast in the early 1950s and Hull from 1955 until his death.

'A growing roster of literary and administrative duties required long, slow rail journeys across the Midlands, with farms and storms and cricket matches sliding past his carriage window'

This life spent in places not quite urban and not quite rural was full, as English lives so often are, of encounters with the British countryside. Family holidays took the young Larkin to Lyme Regis, Dorset, or the Channel Island of Sark and, in the summer vacations at Hull, he visited Northumberland and the Scottish Highlands. A growing roster of literary and administrative duties required long, slow rail journeys across the Midlands, with farms and storms and cricket matches sliding past his carriage window. Most pleasurable for him, it seems, were Sunday cycling excursions over the plain of Holderness, in the East Riding of Yorkshire — sublimely bleak in winter, hazy and bee-loud in summer.

Almost every poem in The North Ship uses scenes or metaphors drawn from the natural world: ‘Birds crazed with flight/Branches that fling/Leaves up to the light’; ‘…rain/Driving across a darkening autumn’; and what may be the most starkly memorable couplet in the collection, ‘Time is the echo of an axe/Within a wood’. In these early poems, Larkin’s characters are always, so to speak, in the landscape and the weather; their appetites and obsessions drenched in sun or wind, even when they stand in a railway station or merely lie in bed.

Throughout his later writing, Larkin recoiled from what he saw as sentimental or mythologised depictions of the natural world. In I Remember, I Remember, he mocked rose-tinted reminiscences of country childhoods, smothered in ‘blinding theologies of flowers and fruits’, and in his interview with Betjeman he dismissed The North Ship as ‘a kind of Yeats-and-water’. His first mature collection, 1955’s The Less Deceived, reflected a new influence—the thwarted post-Romantic realism of Thomas Hardy’s poetry.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

In 2014’s Philip Larkin: Life, Art and Love, the critic and biographer James Booth uses Myxomatosis, one of the darker poems in The Less Deceived, to draw out the differences between Larkin and the most renowned Nature poet of his generation, Ted Hughes. ‘Hughes endows his birds and rodents with human pride, guilt and deviousness,’ he writes, but ‘Larkin respects the non-human otherness of animals’. Larkin’s language in Myxomatosis is, as he observes, attentive to the suffering creature, unpresumptuous about its inner life: ‘You seem to ask’; ‘you may have thought’. The gales and birds and trees of The North Ship are subtly transformed, embodying a Hardyesque conviction that the impressions and meanings we read out of Nature are our impositions. When the narrator of At Grass, observing a shady field of retired racehorses, asks ‘Do memories plague their ears like flies?/They shake their heads’, he reminds himself that the fading recollections ‘Of Cups and Stakes and Handicaps’ are his, not theirs.

'His poetry reminds us that the power of Nature to liberate and to console us lies in its blend of strangeness and familiarity'

A. E. Housman, one of Larkin’s less acknowledged influences, writes in his Last Poems of ‘heartless, witless nature’. Larkin might have admitted the naked truth of this, but in 1964’s The Whitsun Weddings, perhaps his greatest achievement as a poet, Nature is at once richer and stranger, a mirror and a foil for human folly, rapture and loss. In MCMXIV, the soil itself—‘fields/ Shadowing Domesday lines/Under wheat’s restless silence’—is suffused with ominous tranquillity, as its inhabitants march off to the Marne and the Somme. This grasp of a landscape’s deep history is carried over to An Arundel Tomb where, in a magnificently cinematic section, Larkin evokes the passage of centuries through the churn of the seasons: ‘Snow fell, undated. Light/Each summer thronged the glass. A bright/Litter of birdcalls strewed the same/Bone-riddled ground.’

Mortality haunted everything Larkin wrote and this painful yet fruitful tension between the terror of death and a yearning for rebirth runs through the late poems of High Windows. The Trees is an almost mirror image of Housman’s On Wenlock Edge the wood’s in trouble. Larkin’s ‘unresting castles thresh’ as Housman’s do, but, instead of reminding the reader that ‘The tree of man was never quiet’, they seem to murmur more hopefully: ‘Begin afresh, afresh, afresh.’ The collection is bathed in moonlight, from the ‘strong/Unhindered moon’ of Dockery and Son to the ‘air-sharpened blade’ of Vers de Société, but most of all in Sad Steps: the ‘hardness and the brightness and the plain/Far-reaching singleness’ of the moon’s ‘wide stare’, prompting melancholy while remaining ‘high and preposterous and separate’.

Larkin, lunar laureate? He’d have scoffed, no doubt, but his poetry reminds us that the power of Nature to liberate and to console us lies in its blend of strangeness and familiarity. He offers 1,000 paths to a thought at once ancient and always fresh, and at the end of the street, the birds, the trees and the moon — while we are here to find joy in them.

Richard Barnett is a historian of science and medicine and a poet. He is the author of eight books, including Medical London: City of Diseases: City of Cures, a Book of the Week on BBC Radio 4, and Wherever We Are When We Come To The End, a long poem in the voice of Ludwig Wittgenstein's Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. He has written for (inter alia) the Lancet and the London Review of Books, and has contributed to TV and radio documentaries for the BBC, PBS, NPR, China Central and many other networks.