From woodland to Westminster: Can the felling of ancient oak trees be an act of cultural service?

Timber from the Whiligh estate in the Sussex Weald was used to build the vast hammerbeam roof of Westminster Hall — and its custodian still fells trees for very special commissions.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Tucked away deep in the Sussex Weald is the estate of Whiligh. Parkland yields to the undulating hills of a steep valley, with an iron-rich stream running through its cleft. The landscape — woodland, wood pasture and grazing land — is dotted with veteran chestnuts and sycamores, important enough to attract the attention of serious dendrophiles.

But the real treasures here are the pedunculate oaks (Quercus robur), Whiligh's most venerable trees. One such oak, the Whiligh Oak, standing in the curtilage of the Tudor house at the centre of the estate, has a girth of nearly 10 metres and has been dated at somewhere between 1,000 and 1,500 years old.

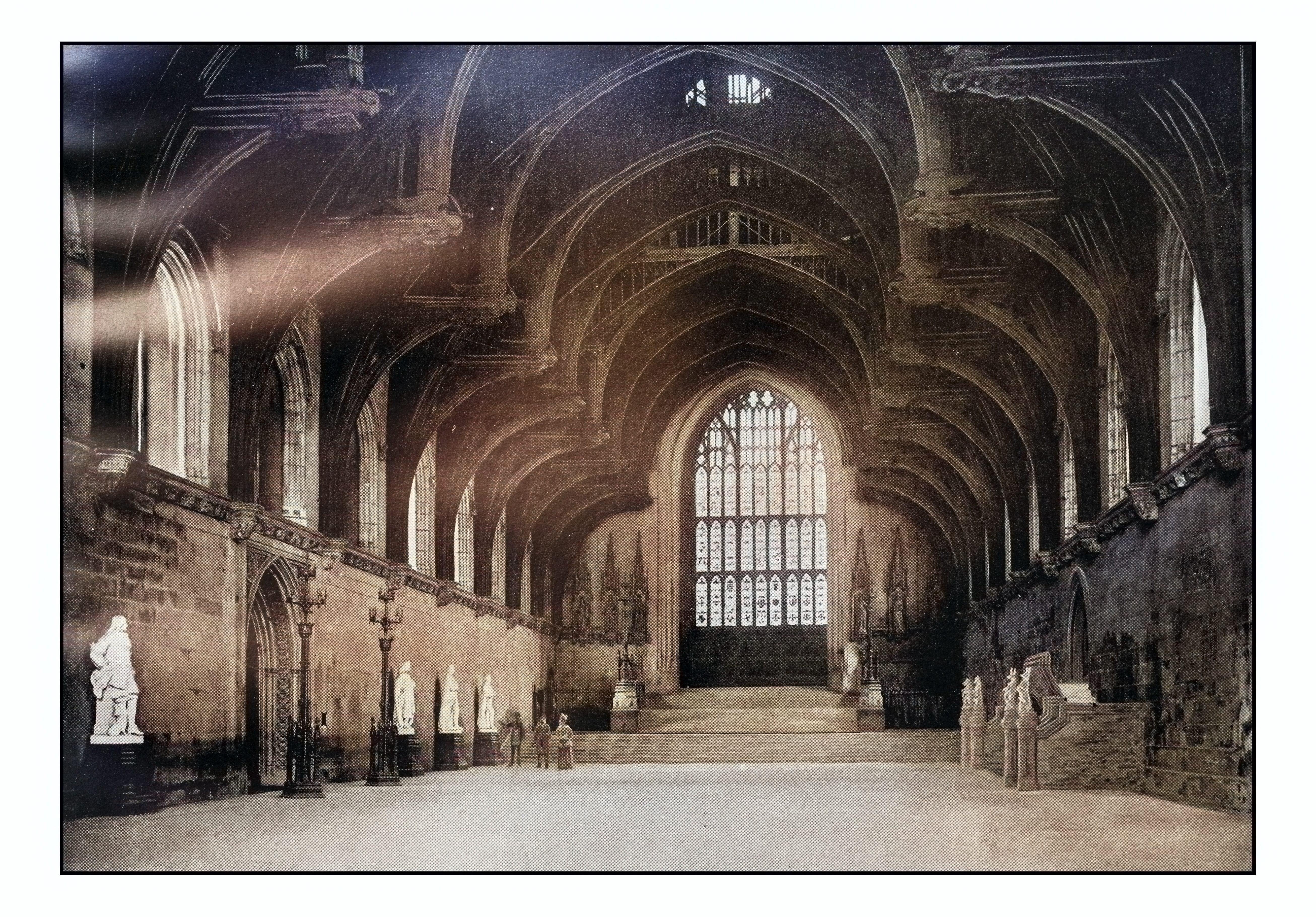

Westminster Hall is the oldest part of the Palace of Westminster and famous for its magnificent hammerbeam roof (the largest medieval timber roof in northern Europe).

Oak timber from Whiligh was used to build the vast hammerbeam roof of Westminster Hall, commissioned by Richard II in 1393. The Palace of Westminster has turned to Whiligh twice in more recent times; in 1913, when deathwatch beetle made inroads into the beams and again after the Second World War, to repair damage caused by an oil bomb. Hampton Court Palace and the Royal Chelsea Hospital have also been the recipients of sturdy Whiligh timbers. Its reputation as a first-class building material spreads all over the world. In the late 1940s, its timber was hauled across oceans to create a memorial chapel to the fallen of the British Empire in New Zealand’s Christ Church Cathedral.

Landowner Michael Hardcastle continues the ancient tradition of using Whiligh oaks for very special commissions, answering a callout for timber from the Sutton Hoo Ship Project in December 2024. The project, based in Woodbridge, Suffolk, aims to re-create the famous 7th-century Anglo-Saxon burial ship with traditional tools and authentic materials, using the original archaeological evidence as a guide.

‘It’s important for good oaks to go to good projects,’ says Michael. Together with master shipwright Laurence Walker, they chose three oaks dating between 180 to 200 years old, felled in April of 2025.

‘We were looking for a certain size of tree to form the ship planks — 1.2 metres in diameter, at least six metres long from the bottom, straight-grained with not too many knots in the bark, and these were hard to find,’ explains Laurence.

The size of the trees, combined with steep terrain to the road, necessitated the loan of a 1940s Caterpillar — once used to shift tanks — from a local haulage company. Once safely received, the team at Woodbridge used Anglo-Saxon style axes to cleave the wood, following the natural grain to create the strongest planks as the original shipwrights would have done.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

A group of people watch the excavations at the site of an Anglo-Saxon ship burial at Sutton Hoo, in August 1939. The site contained a wealth of artefacts, with the ship's rivets becoming irregular (centre) at the location of the funeral chamber which contained a hoard of treasures.

'Many who work with wood prefer French oak for its smooth, tight grain and the predictability that comes with a highly regulated industry'

This felling followed the established philosophy of natural regeneration at Whiligh which is focused on creating space and light for trees to thrive, enabling them to grow into some of the biggest and strongest oaks in Europe. ‘Instead of just looking ahead to the next couple of years we also have to consider the next few hundred,’ says Michael.

For their part, the Sutton Hoo Ship Project has planted more than 400 oaks to replace those donated by the National Trust, the Woodland Trust and private landowners like Michael to the project. ‘We have a site called Saxon Ship Wood local to the site of the ship,’ says Jacq Barnard, project manager. ‘Here saplings are grown from acorns collected at the felling sites, tended by volunteers.’

Whiligh has a history of woodland management going back to Saxon times, and the pedunculate oak thrives in the moist and fertile clay soil of the Weald like nowhere else.

The first known reference to Whiligh is a Charter of 1018, when King Canute granted a ‘certain little woodland pasture’ to Archbishop Aelfstan. Part of this land grant was what is now Whiligh (then spelt Wiglege), meaning ‘a clearing in the wood where heathen rites are practised.’ The Courthope family acquired the estate through marriage in 1515. While paganism has evolved into Anglicanism — of which the church spire cresting Whiligh’s hills reminds us, in a rare glimpse of the world outside the estate — the predominance of the oak in this landscape has lasted more than a thousand years. ‘In a map from the 1400s what is now known as the Whiligh Oak was referred to as “the old oak”, so it was considered ancient even then,’ says Michael.

Almost all of the oaks at Whiligh are naturally seeded. The combination of Tunbridge Wells clay, overlaid with Hastings sandstone, has proven especially conducive to their proliferation. Michael explains how the estate topography, and the surrounding area, have contributed to the creation of such strong, sought-after wood: ‘Over millennia, the clay from the top of the ridges has slid down into the bottom of the valleys. So we have deep, fertile, clay soil in the valleys, and that is where the good, strong oak trees grow that are ideal for timber. The opposite would be those grown on sandy soil, which can look very nice from the outside but when cut down and sent through a sawmill shake and then split.’

England’s woodlands were already in centuries of decline when the First World War broke out in 1914 and they were ransacked for timber to build ships. In 1919, Lloyd George’s government established the Forestry Commission to replenish the nation’s forests. Michael’s ancestor Sir George Courthope, an MP, later Lord Courthope, was one of the earliest commissioners, appointed in 1927. A leading spokesman for the Commission in the House of Commons, he overhauled Whiligh after the First World War to become an exemplar of good forestry. Indeed, it was Sir George’s idea to donate his own oaks to repair the war damage caused to the roof of Westminster Hall.

Although woodlands across the Channel were deeply affected by trench warfare, resulting in the replanting of thousands of trees in the so-called Red Zone — 23,000 acres around Verdun, purchased by the French government after the War — France had already acted to counter the long-term degradation of its woodlands. The Forestry Ordinance of 1669, proclaimed by Louis XIV, introduced systematic forest management practices, which have continued to this day.

Although French and English oak are the same species, French oak trees are mostly found in dense forests and tend to grow tall with few side branches that produce knots. Many who work with wood prefer French oak for its smooth, tight grain and the predictability that comes with a highly regulated industry. French oak is graded and harvested under strict guidelines, whereas it is harder to tell whether English-sourced oak has been cut and seasoned correctly.

‘The French oak industry is well-managed with strong supply chains,’ says Simon Mann from Thorogood Timber, a Colchester-based timber merchant that works regularly with a small sawmill from the Champagne-Ardenne region. ‘It means that we can confidently take on commissions knowing that we can consistently source high-quality timber.’

Winemakers also tend to favour French oak. Gary Jordan owns the acclaimed Jordan Wine Estate in Stellenbosch, South Africa, and winery and distillery Mousehall, in East Sussex, producing Tidebrook wines: ‘From time to time we talk about using English oak rather than French for our barrels, but it is difficult to find English coopers who understand the need to air-dry and stack oak for up to three years before constructing them.’ That said, Gary is planning to make staves from an ancient oak at Mousehall that recently blew over in a storm to age his local wines. ‘That would be the ultimate expression of our terroir,’ he says.

The continuous curation of Whiligh’s oaks by one family, maintained for more than 1,000 years, is the exception in England rather than the rule. Their contribution to monumental building projects worldwide ensures that the characterful English oak, and a little piece of Sussex, will always have a place in history.

Katharine Freeland is a freelance journalist and editor with a background in the history of art and business writing. She has a degree in the History of Art and Architecture, with a specialism in medieval art and history. Over two decades she has written about private wealth, estates and trusts, succession planning, agricultural estates, property, personal finance for HNWIs, family offices, private capital and cultural assets.