Critics be damned, Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral gets Grade I status on advice from Historic England

Looking a bit like a large piece of moon-landing equipment on which you’d best not sit, with indoor lighting that wouldn’t look out of place in a nightclub, the building has ever divided opinions.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Affectionately known to locals as ‘Paddy’s Wigwam’, Liverpool’s Metropolitan Cathedral of Christ the King’s listed status has been upgraded to Grade I on advice from Historic England. It was built in the 1960s to the groundbreaking vision of Modern architect Sir Frederick Gibberd on top of an earlier Sir Edwin Lutyens-designed crypt; construction of a grand, classical cathedral had begun in the 1930s but was scuppered by the war and ‘The Mersey Funnel’, as it is also known, became Britain’s greatest Roman Catholic post-war architectural commission.

Constructed of concrete, Portland stone and stainless steel, giving the appearance, perhaps, of a large piece of moon-landing equipment on which you’d best not sit, with indoor lighting that wouldn’t look out of place in a nightclub, the building has ever divided opinions.

The Crypt is all that remains of an earlier cathedral for Liverpool, designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens in the 1930’s.

Mass is designed to be a visual drama in the progressive, circular, open space, fit for a world post the Second Vatican Council and ensuing changes, including greater congregational involvement. Sixty years later, its appearance is still somewhat shocking and, although it can’t boast the neon writing of Dame Tracey Emin, as its Anglican counterpart (by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott) in the city can, the site is an art lover’s dream.

Tracey Emin's installation in Liverpool Anglican Cathedral. It reads 'I felt you and I know you loved me'.

A special method of cementing coloured glass was invented for installing the central lantern by John Piper and Patrick Reyntiens and other striking artwork includes Elisabeth Frink’s crucifix, bronze relief doors by sculptor William Mitchell showing symbols of the Four Evangelists, various stained-glass windows by Margaret Traherne, Stations of the Cross by sculptor Sean Rice and an enormous crown of thorns or ‘baldacchino’ above the altar designed by Gibberd, made of aluminium rods and incorporating loudspeakers and lights.

The Catholic Metropolitan Cathedral and the Liverpool Anglican Cathedral. Chalk and cheese.

The cathedral's interior continues to divide opinion.

Some would argue that the real shock is that Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral wasn’t already listed Grade I. It certainly could have used assistance over the years. In the 1980s, a high-profile court case saw the Archdiocese sue both Gibberd and the engineers over a leaking roof, pieces of mosaic falling from the buttresses and a bell tower that was too narrow for the drive wheel it required. ‘After four weeks of trial, the case was settled,’ explains Paul Walton, former solicitor for the Archdiocese. ‘Even so, once the cathedral got the money, nobody new how to fix the issues. When Archbishop Kelly was installed in the 1996, the roof was still leaking. It rained on the day of his installation and the water dripped onto his family and guests. The roof was finally fixed later that decade.’

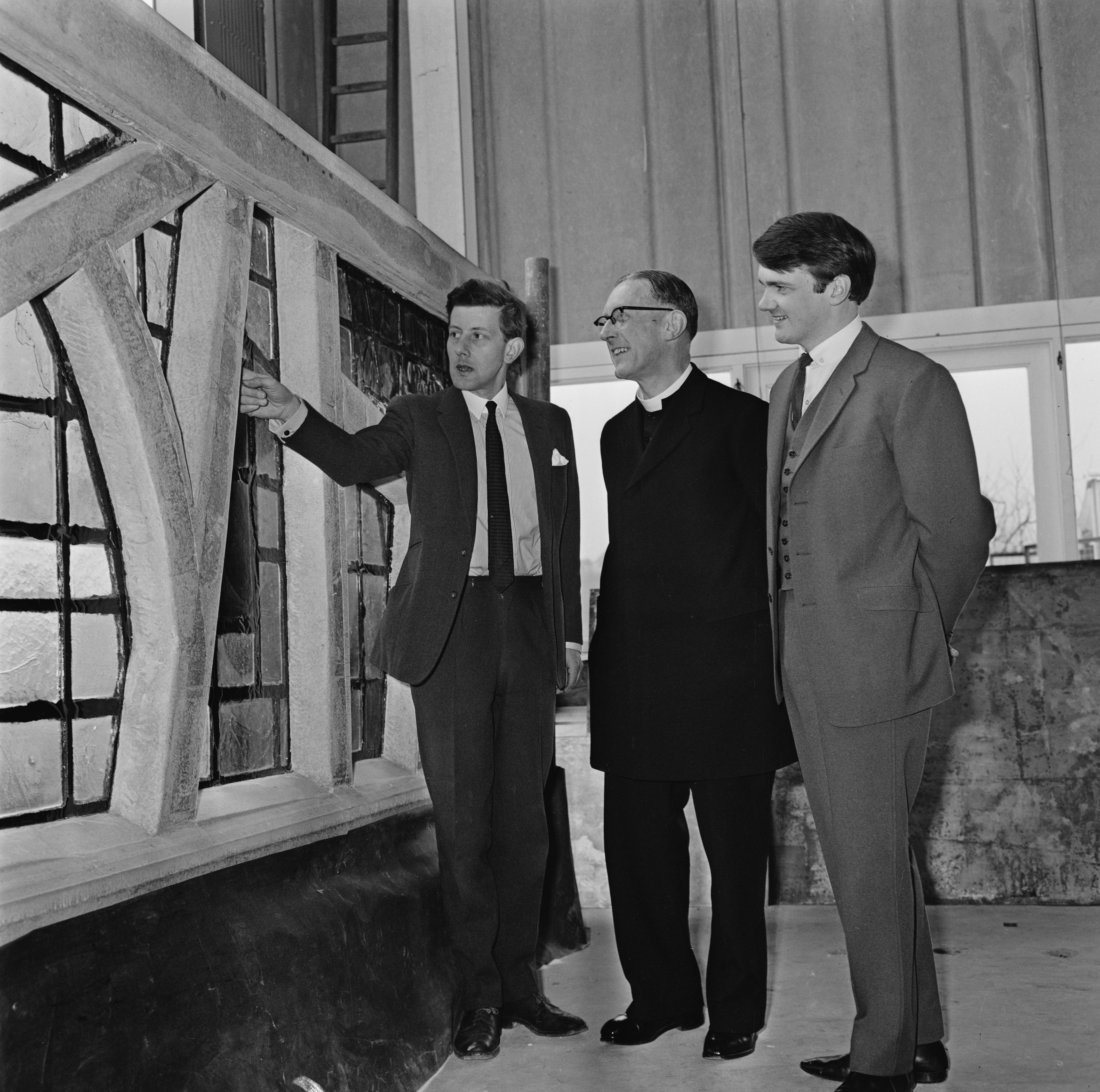

The Archbishop of Liverpool George Beck (centre) with his assistant David Kirby (right) visiting the studio of stained-glass artist Patrick Reyntiens (left) in Loudwater, Buckinghamshire, in 1965, to view the stained glass window panels, which were being made for the Lantern Tower of Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral.

Controversy aside, the cathedral has certainly achieved Gibberd’s aim of giving the city a ‘unique topography’. ‘It commands the Liverpool skyline and is visible for miles around,’ adds Archbishop John Sherrington, Archbishop of Liverpool. ‘The building has been described as “the soul of the city” and brings hope to thousands who visit each year. The colours of the stained glass and revolutionary architectural style help raise their minds and hearts beyond this world to the transcendent and to God.’

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Annunciata is director of contemporary art gallery TIN MAN ART and an award-winning journalist specialising in art, culture and property. Previously, she was Country Life’s News & Property Editor. Before that, she worked at The Sunday Times Travel Magazine, researched for a historical biographer and co-founded a literary, art and music festival in Oxfordshire. Lancashire-born, she lives in Hampshire with a husband, two daughters and a mischievous pug.