Dangerous beasts (and where to find them): Britain's animals that are best left alone

John Lewis-Stempel provides a miscellany of our otherwise benign land’s more fearsome critters.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

When Shakespeare rhapsodised about these isles as ‘a blessed plot’, he could have had our happy lack of dangerous animals in mind. We have only one poisonous snake, the adder (Vipera berus) — Northern Ireland is free even of this serpent — and the surrounding silver sea is devoid of the sort of sharks that bite you in two. Having found bears unbearable, we removed them from the scene. The packs of wolves were similarly sent packing.

Yes, savage and life-threatening animals are luckily found ‘abroad’… or perhaps not. Out there in the non-wilds of Britain exist potentially lethal creatures. Some, such as domestic dogs, could be said to be hiding in plain view; in 2023–24, there were 16 deaths in England and Wales due to canine attacks (the wolf’s revenge, perhaps).

Other could-be killers lurk, hidden or camouflaged. The lesser weever fish (Echiichthys vipera), which has needle-sharp, venomous spines, secretes itself in the shallow, sandy beach waters so pleasant to paddle about in; the yellow-tailed scorpion (Tetratrichobothrius flavicaudis) lives in the dark cracks of walls of buildings. A scorpion? In Britain? Yes: a poisonous scorpion. The stingy-appendaged thing is an invasive species, an accidental import. One can introduce trouble into Eden. Then there are the mislabelled. Horseflies (Tabanidae) do not restrict themselves to biting equids and, although they rarely cause human death directly, they do spread diseases such as rabbit fever. Despite the ‘rabbit’ in the name of the disease, and the ‘horse’ in the nomenclature of the insect vector, tularemia is a life-threatening illness for humans.

The British countryside, pace Shakespeare, is overwhelmingly a safe space. Enjoy it, but respect Nature and give some species a wide berth — such as this dangerous dozen.

Sting in the tail

A confirmed resident in England and Wales, the Asian hornet’s (Vespa velutina) greatest threat is to the honeybee population — it kills up to 50 honeybees a day to feed its nest’s carnivorous young. The insect’s stinger is a whopping ¼in long, a positive insectoid syringe, and for anyone allergic to venom from the Vespidae family (which includes wasps and bees) an attack could be fatal. They also happen to be notoriously bad tempered, waspish even, when interrupted doing their housework. There have been numerous fatalities across the Channel from Asian hornet stings, too — including that of a Normandy gardener, Laurent Duval, last year.

A freak from the deep

Named, aptly, after a type of old warship, the Portuguese man o’war (Physalia physalis) is a convincingly menacing marine creature, really quite the Jules Verne. The animal’s poisonous tentacles can reach 100ft in length and oft the beast comes not singly, but in armadas 1,000 strong. The sting causes rashes, fever and, rarely, death. Although resembling a jellyfish, the animal is in fact a siphonophore: a colony of specialised clones with various forms and functions, from feeding to reproduction, all working together as one. The oddity of the thing makes it that tad more unnerving. The global warming of our surrounding sea is making Blighty an increasingly attractive destination for Physalia physalis.

The (potential) widow-maker

False widow spiders (Steatoda grossa) may not be as life threatening as true black widow spiders, but their fangs can still give a nasty — and venomous — nip. A non-native species, which arrived in fruit crates from the Canary Islands in the 1880s, the eight-legged creepy-crawly has a distinctive bulbous abdomen that sometimes possesses a skull-like pattern, appositely. Although no lethal bites have been recorded in the UK, in 2012 a woman nearly lost her hand after too close an encounter with the arachnid.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

A pain in the foot

Sea urchins (Echinus) live in the coastal shallows, where they feast on whatever floats towards them. Related to sea cucumbers and starfish, their intriguing remains, globes of delicate shell, are often washed up and sold in souvenir shops. When alive, however, their long spines are rather effective at puncturing human feet. Should such an eventuality occur, it is worth hopping along to A&E. The sting is, in rare cases, deadly — but it is always painful and some pain-killing may be required.

Hiss off, or else

The adder, Britain's one poisonous snake.

It would be an exaggeration to say that the adder’s (Vipera berus) hiss is worse than its bite, but our only venomous snake is a shy, retiring thing and only bares its fangs when disturbed — such as you mistakenly treading on it. About 50 to 100 people are bitten annually. Since records began in 1876, there have been only 14 reported deaths from adder bites in the UK and no adder-related demises since 1975. Biting incidents occur chiefly in early spring, when the snake wakes from its winter torpor and is, to be frank, a bit slow on the uptake, or in summer, when it likes to snoozily sunbathe. We must give credit where it is due, however, as no other reptile has brought a British kingdom to ruins. Warned in a dream to avoid confrontation with usurper Mordred’s army, King Arthur tried negotiation. During the talks, according to the Stanzaic Morte Arthur of about 1350: ‘An adder glode forth upon the ground;/He stang a knight, that men might sen/That he was seke and full unsound./Out he brayed with sworde bright;/To kill the adder had he thought…’

Arthur’s party, seeing a sword flash in sunshine, mistakenly believed themselves attacked. Thus ended the life of King Arthur and 100,000 knights in a legendary bloodbath, due to the bite of a single adder and the confusion its slaying caused. Hedgehogs, incidentally, have a degree of natural resistance to snake venom, which handily allows them to hunt adders — making Mrs Tiggy-Winkle a bit of a femme fatale herself.

Killer cows

For a decade or more, Bos taurus has been in the dock because of its methane ‘emissions’ (or, in Anglo-Saxon, its farts), which warm the atmosphere, inducing climate change. As every country person knows, charging cows with responsibility for the End Times was always daft and science is increasingly letting Ermintrude off the gallows. It’s the how, not the cow. Cattle on old-fashioned outdoor grazing are doing more climate good than harm.

Now the rub. Cows in fields really can be B-movie horror stuff. According to the Health and Safety Executive, between 2017 and 2022 cattle killed 32 people in England alone. An average Holstein Friesian, an entirely average cow, weighs 1,700lb, so when it charges and tramples, it becomes a bovine armoured car. Cows are extremely protective of their herd. Accordingly, cows will charge and trample any person perceived as a threat: notably farmers, veterinary workers and members of the public walking through their pasture. Remember this: Daisy, despite her apparent docility, really, really does not like dogs. You may think that Fido is a darling pooch, as he accompanies you on your wander through a cowfield, but the cows see ‘wolf’, and activate their pre-domesticated state of auroch, entering herd-protective mode. Anyone taking a dog into the midst of cows is asking for an express ticket from the gene pool. A cow’s top speed is an udderly fantastic 25mph. That’s faster than Usain Bolt. Are you?

Oh, deer

When speaking of dangerous animals, Bambi’s mummy and daddy probably do not come leaping to mind. After all, she is a doe-eyed beauty; he is a majestic mountain-top Landseer figure in antlered headgear. They are also dense flesh and bone. Thus, by simple physics they make a considerable obstacle when encountered by a travelling car on a prosaic road. A fallow deer (Dama dama) buck weighs in at 176lb. Although cows kill more people one-on-one, some 200 deer and car collisions occur each day, leading to 20 annual deaths. Alas, none of Britain’s six deer species seemingly attended The Tufty Club. Peak danger periods are May, when young males leave the herd, and the autumn rutting season, when deer are on the move and, frankly, their minds are on things removed from how to traverse tarmac and avoid a moving mass of metal. Top Country Life tip: deer are social animals, so the first deer crossing the road in the car headlights is likely to be followed by more.

A critter to get ticked off about

Ticks (Ixodida) are tiny parasitic arachnids that, Dracula-style, attach to warm-blooded animals and suck out haemoglobin until full. The list of the tick’s victims includes us humans. Ticks are deadly, as they spread tick-borne encephalitis and Lyme disease. The latter can cause, inter alia, cardiac attack and partial paralysis (about 1,000–2,000 people are diagnosed with Lyme disease each year in the UK). Ticks can also disseminate other diseases, including Q fever. A tick’s modus operandi is to lurk on long grass or low vegetation, meaning knee-height for humans. Conclusion: in affected areas, put the trews on when walking.

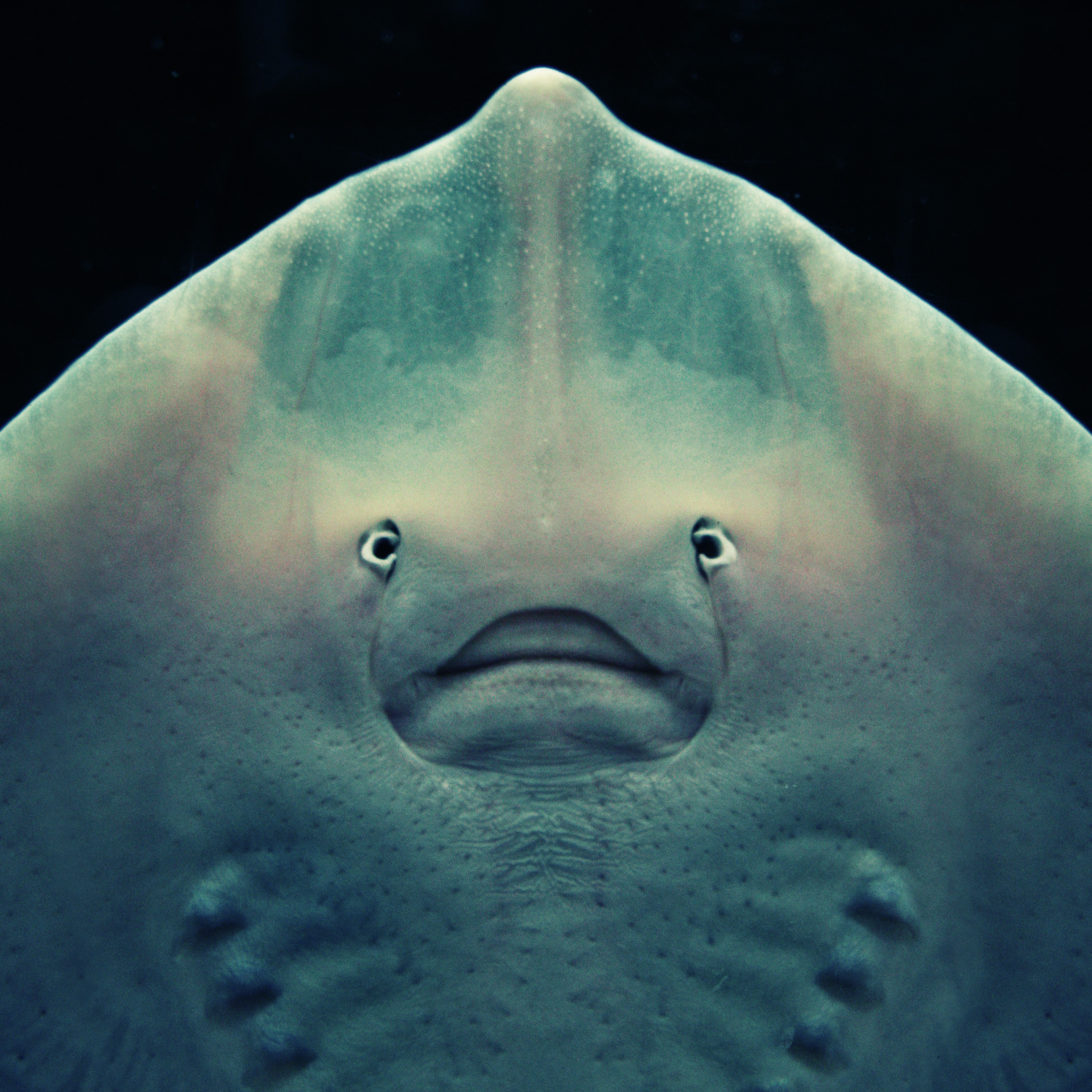

The tail end

Common stingrays (Dasyatis pastinaca), which are ubiquitous around our coastlines and especially in England, can reach 5ft across and weigh 80lb. Which, should one happen to meet the fishy thing when swimming in the briny, may frighten a person to death. Less fancifully, the stingray is called such for the good reason that it has a barbed and venomous tail that, when whipped around defensively, can pierce human skin. The Australian celebrity conservationist Steve Irwin was fatally pierced in the chest by a stingray in 2006.

A plague on all our houses

Historically, the real contender for most dangerous organism ever extant in these isles is Yersinia pestis. That is: the cause of the Black Death. Between 1348 and 1350, the plague killed an estimated one-third to half of Britain’s population, roughly 2–3 million people. There were subsequent pandemics caused by the bacterium, transmitted principally via fleas and rats, most notably the Great Plague of 1665–66. Thankfully, plague is currently absent from Britain, although active abroad, and sometimes in unsuspected locations. In July of this year, there was a plague death in Arizona, US. Advanced civilisation is not always the bastion one hopes — a small, if harsh, lesson from Nature.

Hair-raising stuff

Few caterpillars in Britain pose a problem to humans, but the oak processionary moth caterpillar (Thaumetopoea processionea) is the exception to the rule. When touched, the caterpillar’s toxic hairs may cause vomiting, rashes, breathing difficulties and other allergic reactions. The larvae can release the hairs intentionally as a defence mechanism. The oak processionary is a non-native pest, accidentally introduced from southern Europe in 2005. As the creature’s moniker indicates, it lives in oaks and moves about in creepy, nose-to-tail processions.

Tiddles, the furr-ocious mass murderer of urbia

Let’s not be human-centric in evaluating Britain’s most dangerous creatures. If one were a bird or small mammal, you’d probably cite the domestic cat as the national killer sans pareil. Research suggests that Felis domesticus, of which there are at least 9.5 million specimens in the country, kills up to 270 million wild animals annually, a quarter of them our beloved tweety feathery things — which is cat-a-strophic.

This feature originally appeared in the November 5 2025, issue of Country Life. Click here for more information on how to subscribe.