Britain's most entertaining (and a little bit salacious) country house scandals

'Country houses seem to have harboured more than their fair share of scandals,' says Adrian Tinniswood, who recounts some of the most shocking.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In 1792, Sir Henry Harpur Crewe of Calke Abbey married Nanette Hawkins. This shocked his neighbours, not because Hawkins was already his mistress, but because she had been a lady’s maid. Sleeping with a servant was one thing, but marrying one was something else entirely, and rather than face the ensuing scandal, Sir Henry and Hawkins removed themselves almost completely from county society, living the rest of their lives in semi-retirement at Calke.

Perhaps because of their status and the status of their occupants, country houses seem to have harboured more than their fair share of scandals: the housemaid sent packing when she could no longer conceal her pregnancy; the master of the house, caught out in some minor financial irregularity, who retired to his study with a bottle of whisky and a service revolver for company. And when such secrets came out, lives — and deaths — were played out in a glare of publicity, accompanied by howls of outrage from a public which lapped up all the sordid details, leaving the victims and their relations to brazen it out or, like Sir Henry and Nanette, to hide away from the censure of neighbours.

The exterior of Calke Abbey in Ticknall, Derbyshire. Owned by the Harper family for nearly 300 years, the house was sold to the National Trust in 1985 in lieu of death duties.

Emily, Duchess of Leinster, embarked on an affair with her children’s tutor, a Scot named William Ogilvie, both before and after the death of her husband, the 1st Duke, in 1773. Their relationship was common knowledge, and for a while she ignored the whispers that her most recent child (she had 22) had been fathered not by her ailing husband, but by Ogilvie. However, on her daughter’s wedding day at the Leinsters’ magnificent Palladian seat of Carton House in Co Kildare, her son-in-law to be, the Earl of Bellomont, denounced Emily as ‘a whore’ and threatened to leave his bride at the altar if she didn’t learn to behave respectably. That was enough to convince her that it was time to either give up her lover or marry him. The couple fled to France where, in October 1774, they were married.

Mésalliances have long always been music to the scandalmongers’ ears. In May 1884, a month before his 21st birthday, Willie Brudenell-Bruce, heir to the marquessate of Ailesbury, married Julia Haseley, better known as the music hall artiste Dolly Tester. He was said to have won her in a fistfight at a race meeting. Within a few years Brudenell-Bruce had succeeded to the title, the ancestral seat of Tottenham House in Wiltshire and the 40,000-acre Savernake estates that surrounded it. Dolly didn’t play a large part in Brudenell-Bruce’s life, which consisted of drinking, chasing other actresses and backing the wrong horses. No one took much notice until the summer of 1891 when Brudenell-Bruce, up to his eyes in debt to moneylenders to the tune of £230,000, went to court for permission to break an entail and sell Tottenham House. He was fiercely opposed in this by his family, who took the case right up to the House of Lords while the nation followed the labyrinthine ways of the Settled Land Acts in their morning newspapers and Brudenell-Bruce carried on drinking and spending. He eventually won his permission, but it came too late: in April 1894, at the age of 30, he died in the home of another actress with whom he was living at the time. He was due to be declared bankrupt the following day.

'He was even less impressed to discover that his new daughter-in-law already had a child, the father of whom was currently serving 18 months in Pentonville for fraud'

Music hall artistes figured frequently in the aristocratic scandals of late-Victorian and Edwardian Britain. The 4th Earl of Clancarty of Garbally Court in Co Galway was not impressed to open his newspaper one morning in 1889 to find that his 20-year-old son and heir, Viscount Dunlo, had just got married. He was even less impressed to discover that his new daughter-in-law, Belle Bilton, already had a child, the father of whom was currently serving 18 months in Pentonville for fraud, while she supported herself by performing on the halls as one half of a sister act, Flo and Belle. The Earl packed his son off to Australia (without his bride) and employed an army of private detectives to uncover evidence of Bilton’s adultery.

When they couldn’t find it, they invented it, and the resulting divorce case, which went on for six days, was one of the most famous in Victorian legal history. At the end of it, the accusations against Bilton were found to be untrue and she left the court to applause from the gallery and cheers from crowds gathered in the street.

The same couldn’t be said for the Earl and his son. ‘The youthful heir to the Earldom of Clancarty is obviously not overburdened with brains,’ declared The Daily Telegraph, attacking him for his weakness in deserting his bride. The Earl’s behaviour towards his daughter-in-law was hard and unfeeling, said The Times. Reynolds’s Newspaper went further, declaring that ‘in all the disgraceful records of the British peerage we doubt if anything can be found that surpasses in sheer unadulterated blackguardism the conduct of Lord Clancarty in the matter,’ adding that ‘if Lord Dunlo is a contemptible dolt it is little to be wondered at when he is the son of such a father.’

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

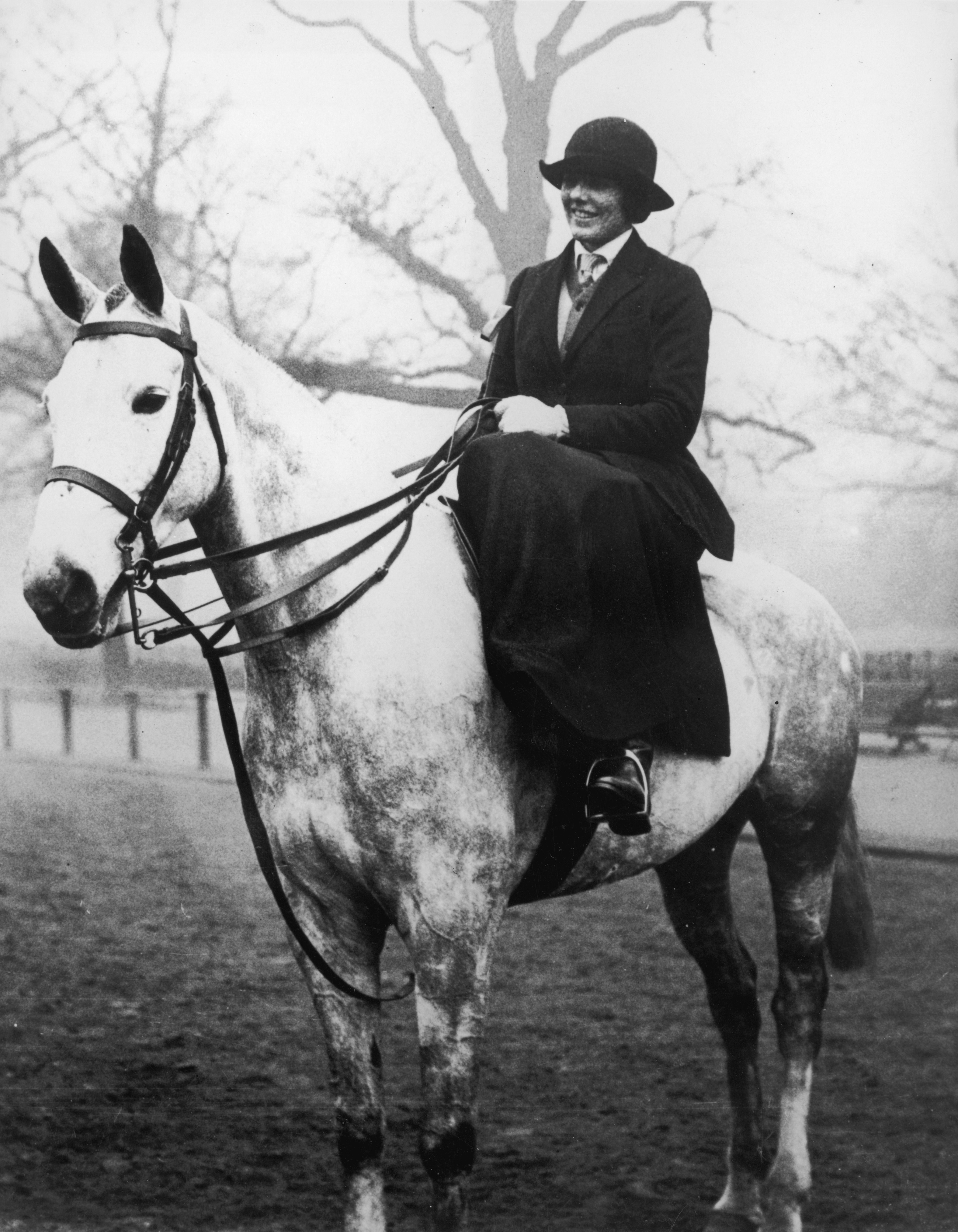

Lady Ampthill, born Christabel Hulme Hart, divorced her husband in 1937 after claiming a virgin birth. An accomplished horsewoman, in later life took to travelling the world.

The most bizarre country house scandal of all had its origins at Oakley House in Bedfordshire, a 13-bedroom mansion remodelled by Henry Holland around 1750 for the Dukes of Bedford. At the end of the First World War, Oakley passed to a Bedford cousin, Arthur Russell, 2nd Lord Ampthill, and a few years later it shot to fame as the scene of an event that rocked the nation — nothing less than a virgin birth.

The virgin in question was Lord Ampthill’s daughter-in-law, Christabel Hulme Hart. Hulme Hart, a Mayfair couturier, married the Hon John Russell, heir to the Ampthill barony, in 1918. But just before the wedding Hulme Hart told her husband-to-be that she didn’t want children for a while, so they weren’t going to be sleeping together in the foreseeable future.

He took this news surprisingly well. But as the months went by, the strain began to tell. In 1919 he bought Hulme Hart a copy of Marie Stopes’s Married Love and suggested they might use some form of birth control? ‘No,’ she said. In 1920, he appeared in her bedroom brandishing a gun and threatening to shoot her cat. She remained unmoved. So he turned the gun on himself and said he would blow his brains out there and then if she did not consummate the marriage. It made no difference.

'There had been what she called "Hunnish scenes" in which her husband had tried and failed to have sex with her'

Then in the summer of 1921, Hulme Hart told her husband she was expecting a baby; and that October she gave birth to a bouncing boy. Her husband’s unsurprising response was to petition for divorce. The last time they had shared a bed, he said, was when they had been put into the same room while staying with his parents at Oakley House the previous December. On that occasion, no physical contact of any kind had taken place. Hulme Hart hadn’t even kissed him since August 1920.

His wife gave a different version of events. She told the divorce court that while they were at Oakley, there had been what she called ‘Hunnish scenes’ in which her husband had tried and failed to have sex with her. She had also had a soak in a bath recently left by her husband — perhaps this could have led to her pregnancy?

Then her lawyers dropped a bombshell. Doctors who examined Hulme Hart while she was pregnant would testify that she was a virgin.

The arguments over what the press called ‘the Russell baby case’ dragged on through two divorce trials. At stake was the boy’s future as heir to the Ampthill barony. The first trial was inconclusive, and the second, described by one of the Sunday papers as ‘probably the most talked of divorce case of a generation’, ended in defeat for Hulme Hart. The reputations of both husband and wife were in tatters. Their most private and intimate habits had been discussed at length in open court and reported in prurient detail in the press. The future Baron Ampthill was widely regarded as effete and unassertive for allowing Hulme Hart to dictate the terms of their relationship, and the revelation that he liked to dress up in women's clothes didn’t help. His wife was seen as unnatural for refusing to accept her wifely duties. Both were condemned for having ‘freakish’ manners and morals.

Hulme Hart appealed against the verdict, taking it right up to the House of Lords, and in a remarkable judgement in May 1924 the Lords overturned the decree nisi on a legal technicality by a majority of three-two, thus legitimising the two-year-old Geoffrey Russell and his virgin birth. The Ampthill heir’s mother turned to fiction, if she hadn’t already, and in 1925 published a novel called Afraid of Love, ‘the study of a woman who resolved to be dependent on no man’.

Adrian Tinniswood joined the 'Country Life podcast' in October 2025. You can listen to him in conversation with James Fisher, here.

Professor Adrian Tinniswood is the author of Houses of Guinness: the Lives, Homes and Fortunes of the Great Brewing Dynasty. He is director of Graduate Programmes in Country House Studies at the University of Buckingham, and adjunct professor of history at Maynooth University. He and his wife live in the west of Ireland with their cat Matilda