100 years of the photobooth, the essential piece of party paraphernalia beloved by Salvador Dali, Andy Warhol and Beyoncé

On the centenary of the photobooth, Will Hosie looks back on a hundred years of self-portraits.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

I like to play a game at parties called ‘Come in, Mr …’. You have to replace the ellipsis with a category, which you decide upon in a group as one person sits outside awaiting their fate. ‘Come in, Mr Kitchen Utensil!’ the rest of the party might say, or ‘Come in, Mr Prime Minister!’ The chosen player then has to mime something, or someone, in that category. I’ve previously chosen to imitate Boris Johnson by pretending to hide in a fridge.

My favourite category, however, is ‘Come in, Mr Party Paraphernalia’. One player has previously done a full rendition of the Saturday Night Fever choreography in an attempt to evoke a disco ball. I’m always surprised at how few people opt to mime a photobooth, since it would be among the easiest items to pull off. Perhaps that’s because the device has become so ubiquitous at parties that we no longer think of it as paraphernalia so much as elementary.

Ruby Murray (1935-1996) is observed by a small group of admirers as she has her picture taken in a photo booth at Brighton Pier, in 1956.

The first fully automatic photographic machine, then called the Photomaton, appeared in New York City 100 years ago. It was created by a Siberian immigrant, Anatol Josepho, with its first outpost on Broadway near Times Square. More than 250,000 citizens used the photobooth in its first year, paying 25 cents and waiting patiently for eight minutes while their photo strips developed. Nowadays, it takes all of 10 seconds.

The Photomaton later spread throughout the city and across the USA; the model located at the Strand Theatre in Manhattan was so successful that it kept the owner’s extended family employed during the Great Depression. By the 1960s, photobooths had become an artistic medium in their own right, with Andy Warhol using them for his series of self-portraits: three of them with sunglasses on, one with them off. To this day, the four-picture strip remains the best-known format for the photobooth print, although some now adhere to a 2x2 format and others are altogether different, offering something more three-dimensional.

Indeed, many parties now feature an alternative to the traditional photobooth, called the 360 video booth, where a camera on a rotating arm swivels around a stationary platform and captures high-definition, social media-ready videos of whoever is standing on it, that a myriad effects can be layered onto. The industry is growing, projected to reach $1.3 billion in global market value by 2033, driven largely by demand for such experiences.

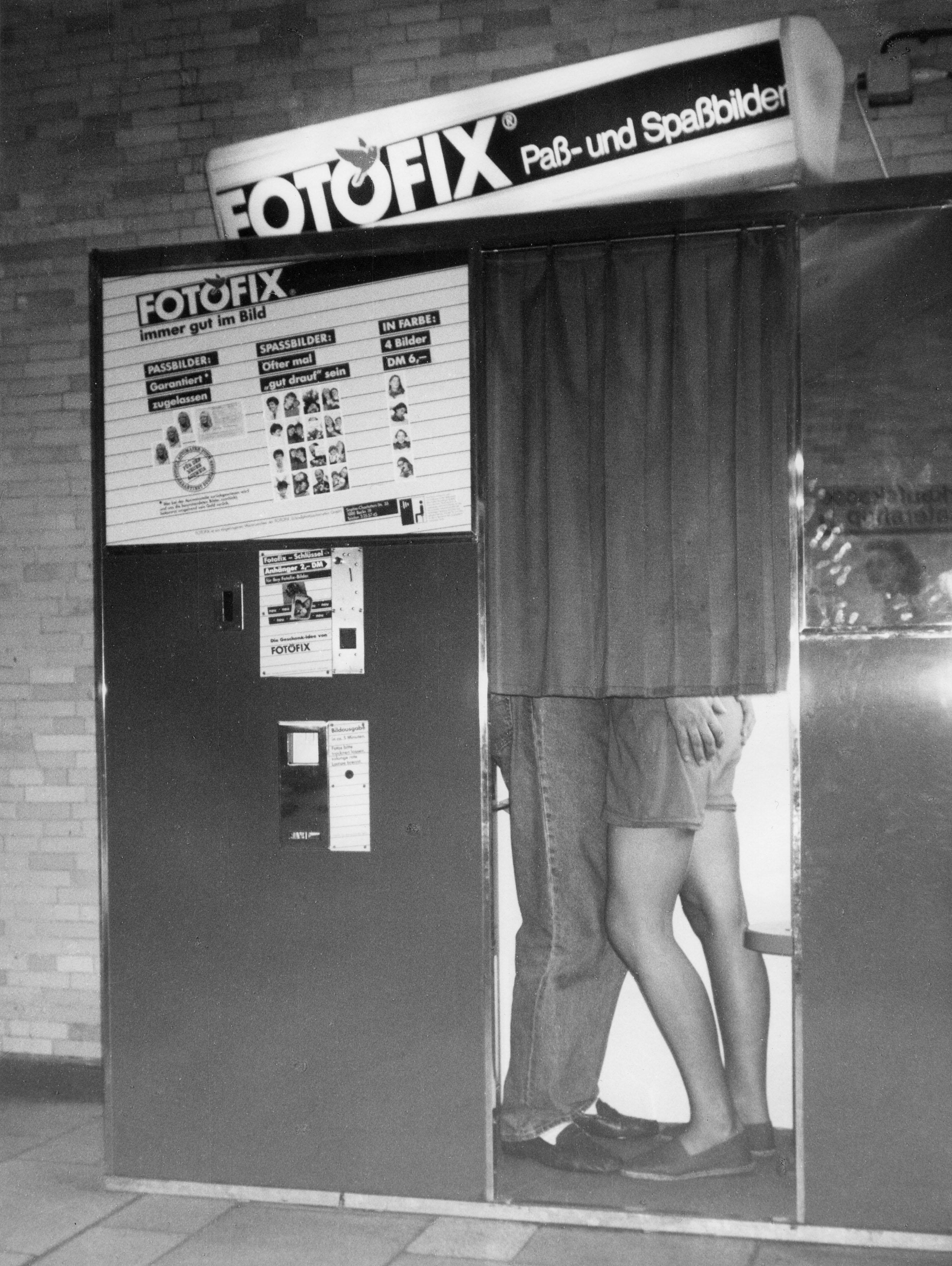

A photobooth in East Germany in the 1980s.

Still, there’s something alluring about the old-school Photomaton. The device’s archives offer something of a bulletin on 20th century movers and shakers. Salvador Dalí was an early adopter, taking pictures of him and his wife Gala in a Photomaton in the 1930s, before he grew his moustache. These have become legendary: a rare portrait of the artist as a candid young man; a snapshot of authenticity. Indeed, the nature of the photobooth, in which users draw a curtain and take pictures away from prying eyes, means that it has long been somewhere for people to escape the perception of others.

This can mean two, very different things. For those whose life is a performance, like the late Dalí, the photobooth was an opportunity to be oneself. There are records of pictures taken in photobooths by same-sex couples in the decades before such relationships were legalised, the isolation provided by the booth minimising the risk of exposure. For others, the photobooth does precisely the opposite: it is an opportunity to be someone else entirely and to don a costume. ‘It gives people the freedom to hide behind a different persona,’ explains Johnny Roxburgh, a wedding designer and self-styled ‘party architect’. ‘At a party last weekend, we had full-head masks so that people could become a donkey or a cow. It allows people to clown around with the freedom of anonymity.’

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Salvador Dalí and his wife, Gala. She was his muse and appeared in many of his works.

Long after Dalí first tried the Photomaton, the modern-day photobooth became something of a promotional vehicle. Arguably the best known model is the MTV TRL photobooth at Times Square Studio, which became a rite of passage for superstars from 1999 to the mid-2000s. Mariah Carey, Britney Spears, Eminem and a young Beyoncé all went behind the hallowed curtain, pulling faces and flashing the sort of big smile that says: ‘I’m here: I’ve made it.’

Nowadays, a photobooth is still one of the best marketing tools out there. If one is throwing a party to launch a product or celebrate a milestone, there’s no better way to let the whole world know than by hiring a photobooth for the evening (prices start at £150) and ensuring that the name of the brand or the nature of the party features on the prints which are inevitably snapped for social media.

All of us normal folk who aren’t Beyoncé or Eminem have also entered a photobooth at some point in our lives, perhaps at a party — where it might have had a funny background in keeping with the theme — though more likely in an Underground station to get some last-minute passport photos. Regardless of the context, the one thing that makes the photobooth so enduring is precisely the fact that it is such a great leveller. By shooting people head on and giving them the agency over what face to pull or what props to use, it gives back precisely what is put into it. Of all the world’s cameras, it is probably the most honest. In our day and age, especially, that feels like something worth celebrating.

Will Hosie is Country Life's Lifestyle Editor and a contributor to A Rabbit's Foot and Semaine. He also edits the Substack @gauchemagazine. He not so secretly thinks Stanely Tucci should've won an Oscar for his role in The Devil Wears Prada.