Josephine Baker and the remarkable women of espionage who helped win the Second World War

On the 80th anniversary of VE Day, we salute five women who worked tirelessly in the shadows to bring about an Allied victory.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

When real life inspires fiction: in Sebastian Faulks’s novel Charlotte Gray (which was made into a film starring Cate Blanchett), a heroine of the SOE parachutes into occupied France.

'And Joshua sent out… two men… to spy secretly, saying, Go view the land, even Jericho. And they went, and came into an harlot’s house, named Rahab, and lodged there.’ Rahab thus combined the oldest and second oldest professions, creating ‘sexpionage’.

Churchill knew the importance of intelligence. He’d written the biography of his ancestor the Duke of Marlborough, Britain’s most complete general, who’d said: ‘No war can be made without good and early intelligence.’ Churchill’s most famous source was ‘Ultra’, the breaking of the German Enigma code at Bletchley Park.

However, human intelligence (‘humint’) had a quality of its own and, in June 1940, after the fall of France, he set up the Special Operations Executive (SOE) ‘to co-ordinate, inspire, control and assist the nationals of the oppressed countries’ in sabotage and subversion. Or, as he put it more bluntly, to ‘set Europe ablaze’. SOE would become a major source of humint.

Josephine Baker was no harlot, but she pushed her charms to the limit both on and off stage. ‘I wasn’t really naked,’ she would say. ‘I simply didn’t have any clothes on.’ Born in 1906 in St Louis, Missouri, US, to an African-American laundress and a white drummer father, who abandoned them both shortly after her birth, the then Josephine McDonald ran away from home at 13 to work as a waitress at a club, got married for a few weeks and took up dancing.

At 17, twice married and separated, she landed a chorus role in a musical and moved to New York to sing and dance at the famous Plantation Club. Two years later, she was in Paris in La Revue Nègre, sensationally performing the Danse Sauvage in only a feather skirt and socialising with Germans on the embassy party circuit.

In 1939, the storm of war gathering, Baker was recruited by French military intelligence, the Deuxième Bureau. When war broke out in September, she switched attention to the Japanese and Italian embassies — still neutrals — and then, after the fall of France, began sending reports on the collaborationist Vichy government to Gen de Gaulle’s Free French in England.

Josephine Baker receives the Legion of Honor and the Croix de Guerre with palm on August 19, 1961, from General Martial Valin, former Commander-in-Chief of the Free French Air Force, Chief of General Staff of the French Air Force, and Inspector General of the Air Force.

Confident in her celebrity status, she also travelled in neutral Spain and Portugal, picking up details of Axis troop movements at parties, excusing herself to make notes when ‘powdering her nose’ and secreting them in her bra. ‘They would have been highly compromising had they been discovered, yet who would dare search Josephine Baker to the skin?’ she wrote later. ‘When they asked me for papers, they generally meant autographs.’

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Spies being rarely alike, even so, there could scarcely have been a greater contrast with Baker than Nicole Trahan, only 13 and at boarding school in France when the Germans invaded. On re-joining her parents in England — a French businessman and French mother — she told them that, as soon as she was old enough, she wanted to ‘drive an ambulance or something’.

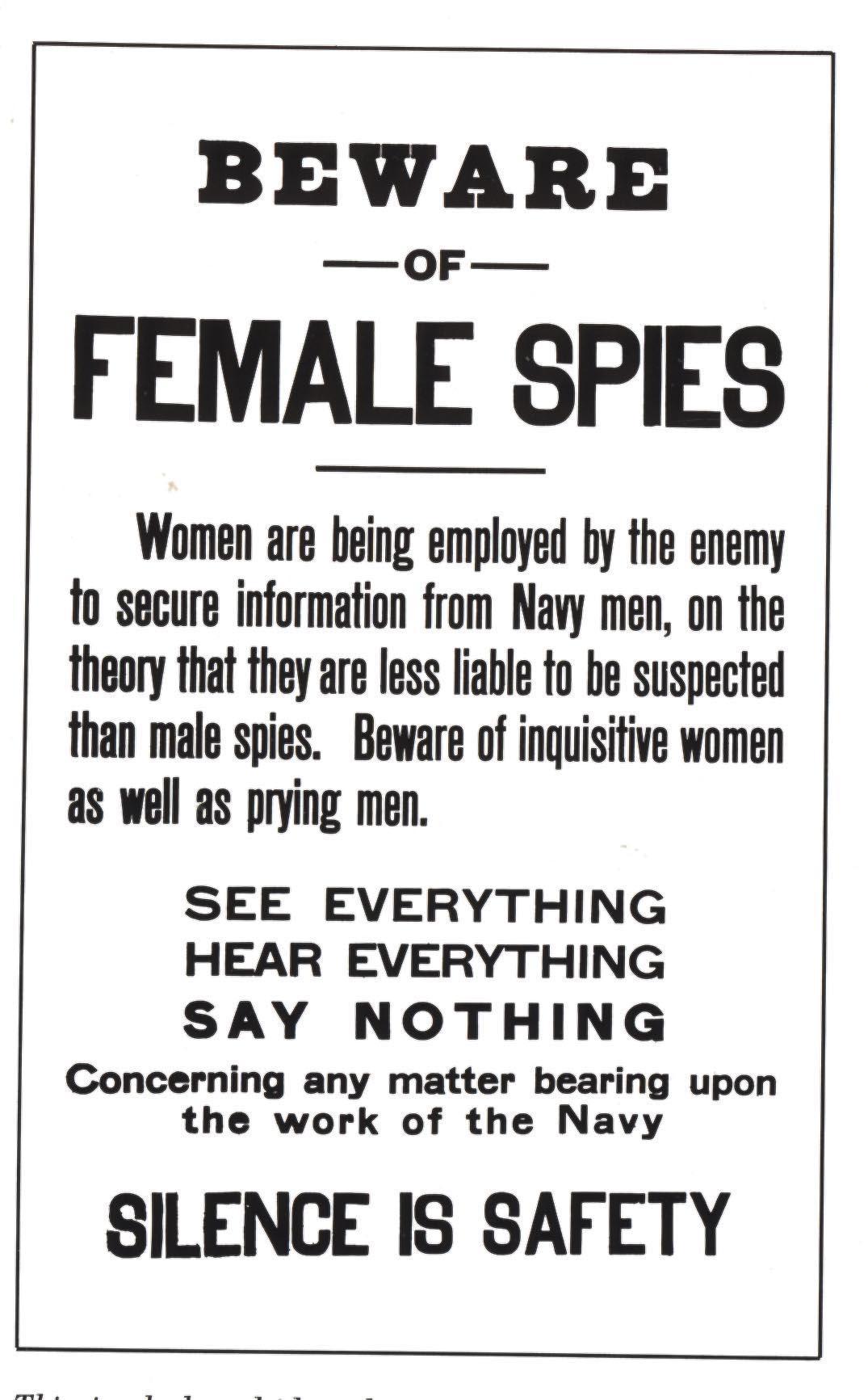

The ‘something’ proved remarkable. In 1942, Churchill gave approval for SOE to use women as couriers, being less conspicuous to the Gestapo, as able-bodied men were expected to be working, not cycling about. Still only 15 and now ‘Nicola’ to her English school friends, she was interviewed by a ‘Major Tom’ in Manchester. Bilingual, knowing the country, young and, in her own words, ‘so plain as not likely to turn heads’, she was ideal courier material. Soon after her 16th birthday, she began parachute training at RAF Ringway (now Manchester airport) and practising emplaning and deplaning at night with the RAF’s Westland Lysander, the short take-off and landing aircraft used for clandestine missions. (The propeller was always kept turning at improvised airstrips.)

In December 1943, Nicole, codename ‘Teddy’, was sent on her first mission, to Valençay between Poitiers and Orléans on the Maquis’s (French resistance) ‘Wrestler’ circuit. Wrestler was originally inside Vichy France’s unoccupied zone, despite the fact that German and Italian troops had by now taken direct military control of the entire country. Although thin on the ground, their radio direction finding was formidable and they frequently benefited from the co-operation of the French gendarmerie. She was there for two weeks — either side of the full moon, for easier insertion and extraction — but home in time for her 17th birthday. Many more missions followed, until, in 1944, after D-Day, she joined up with the French Forces of the Interior, staying with them until the war’s end.

SOE couldn’t function without telecommunications with agents in the field and Anne Maynard was one of its fastest (and youngest) Morse telegraphists. Born in Peshawar, India (now Pakistan), in 1924 to an army family, at 12 she was sent home to board at an Essex convent school. At a party in 1943, she met a friend who told her she was joining the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry (FANY). This was an auxiliary organisation, which, as was the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF), was also a fertile recruiting place — and cover — for SOE. She didn’t know this, but she thought FANY sounded fun.

After an interview in London, mystified, Maynard was sent to a ‘large gloomy house’ near Banbury, Oxfordshire. The next day, having signed the Official Secrets Act, she was told about SOE and that she’d been selected for training as a Morse operator. Practising for eight hours a day for three months, she reached 30 words per minute, a ‘word’ being a sequence of five Morse letters. Speed was vital because German direction-finding now needed only 15 minutes to fix the transmitting point on a map. An agent therefore had to be able to send the message as fast as possible and without being asked to repeat.

Anne Maynard (second from left) pictured in 2009 with other SOE agents and a former member of the French resistance.

‘Pippa’ Latour was one of those who relied on the receiver’s skill. She’d parachuted into Normandy in 1944, aged 23, to join the Maquis’s ‘Scientist’ circuit as their wireless operator — or, in SOE slang, ‘pianist’. Her father, a French doctor, had been killed in the Belgian Congo. Her English mother had subsequently married a racing driver in Kenya, where Pippa was brought up until going to secretarial college in England. When war broke out, she joined the WAAF as a mechanic, but, when her language skill was revealed, she was sent for what was coyly referred to as ‘special training’.

At first, the SOE selectors weren’t convinced. ‘Quite unsuitable,’ said one female agent-turned-trainer. ‘A cheerful little scatterbrain… uncontrolled and stubborn.’ Yet her French was fluent, her looks were youthful and Gallic and she already knew Morse. Further training speeded it up, she became handy with weapons, and two ‘old lags’ — a cat-burglar and a peterman — taught her how to climb walls and pick locks.

One day when bicycling, posing as a soap seller, she was arrested in a routine sweep and taken to the local gendarmerie. The SOE’s technical branch had miniaturised the tools of her trade, however: ‘I always carried knitting because my codes were on a piece of silk. I had about 2,000 I could use. When I used a code, I would just pin prick it to indicate it had gone. I wrapped the piece of silk around a knitting needle to insert it in a flat shoelace which I used to tie my hair up.’ At the gendarmerie, ‘a female soldier made us take our clothes off to see if we were hiding anything. She was looking suspiciously at my hair, so I pulled my lace off and shook my head. That seemed to satisfy her. I tied my hair back up with the lace. It was a nerve-racking moment.’ It was the first of several; however, each time, her childlike gaieté somehow got her through.

Countess Krystyna Skarbek was Churchill’s favourite spy, said his daughter Sarah. Churchill had inordinate faith in titles — despite the frequent let-downs — and, in March 1941, the Countess produced a priceless piece of intelligence at a pivotal moment of the war: microfilm of the German military build-up near the Polish border with the Soviet Union. Churchill used it with other intelligence to warn Stalin, although Stalin couldn’t believe the Germans would invade. When they did three months later, the surprise was total — but, if the microfilm hadn’t served to alert Stalin, it certainly now gave Churchill considerable moral authority with his new ally.

Skarbek’s story is the stuff of old Mittel europa — of Dangerous Moonlight and The Prisoner of Zenda. Born in Warsaw in 1908, to Count Jerzy Skarbek and an heiress of Jewish descent whom he’d married to save the family estate, Krystyna grew up riding, shooting, skinning game and generally running wild. Following a short-lived first marriage, she met a Polish diplomat when skiing, Count Jerzy Giżycki. They married in 1938.

When Germany invaded Poland the following year, the couple were in Ethiopia, but immediately left for London. Here, Skarbek met the Australian George Taylor of the Secret Intelligence Service (MI6), soon to be SOE’s chief of staff. He was instantly won over — or, perhaps, bowled over, for she’d once competed in the Miss Poland competition. ‘She is a flaming Polish patriot, an expert skier and great adventuress,’ he reported. ‘I really believe we have a PRIZE.’

Skarbek became the service’s first female spy, soon skiing across the Hungarian-Polish border laden with money, arms and explosives, then bringing back intelligence, as well as escapees. In January 1941, she was arrested by the Gestapo, together with her latest lover, a Polish army officer and agent. After two days of interrogation, she bit her tongue to make it seem that she was coughing up blood. It worked: she and her lover were released as likely tuberculosis sufferers.

Acquiring a British passport with the name ‘Christine Granville’, Skarbek worked in Cairo for a spell with SOE, trained as a ‘pianist’ and, a month after D-Day, parachuted into southern France to act as courier to Francis Cammaerts, the SOE’s man east of the Rhône. Soon, she was his second-in-command, although her most daring exploit came when the Gestapo arrested Cammaerts and two other agents. Brazenly posing as a British agent sent to obtain their release and with the help of a two-million franc bribe, Skarbek told the Gestapo’s commandant that the Allied invasion was imminent and he would be shot if they were executed. It worked: they were released.

Skarbek, whose charms could scarcely have saved her if her Jewish blood had been discovered, was awarded the George Medal.

When peace came, the soldiers held their victory parades and wrote their histories, whereas, for decades, the spies lay low. Baker was inducted into the Panthéon in Paris four years ago, almost 50 years after her death — the first black woman to receive the honour. Trahan became a health visitor with the Soldiers’, Sailors’ and Airmen’s Families Association (SSAFA). She never married, retiring to the most tucked-away village on Salisbury Plain, where she lived until 97, the image of Miss Marple.

Maynard joined MI6, married Myles Ponsonby of the Foreign Office and worked in Cyprus, Beirut, Indonesia, Kenya and Mongolia. She died aged 98, the last surviving SOE telegraphist. Latour moved to New Zealand, where she died aged 102, the last surviving female agent in SOE’s F (France) Section.

Skarbek soon fell on hard times. After a string of menial jobs in London, she took work as a stewardess on cruise ships. On one voyage, she had an affair with a steward who became obsessive when she jilted him. In June 1952, returning to the rooms she rented, she found him waiting for her. He stabbed her to death (and was hanged 10 weeks later). The stories of these remarkable women, however — and many like them — are still only half told.

2025 marks 50 years since Josephine Baker's death — click here to read more about her extraordinary life.