Sign of the times: In the age of the selfie, what’s happening to the humble autograph?

When Ringo Starr announced that he was no longer going to sign anything, he kickstarted a celebrity movement that coincided with the advent of the camera phone and selfie. Rob Crossan asks whether, in today’s world, the selfie holds more clout than an autograph?

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

‘This is a serious message to anyone watching my message right now, peace and love!’ This is how the world’s most famous drummer began a video message, uploaded to YouTube in 2008. ‘Please after the 20th October do not send fan mail to any address that you have, nothing will be signed’ continues Ringo Starr. Why? Because he had ‘too much to do’. The Beatle has subsequently doubled down, voicing his displeasure at the items he has been asked to sign being re-sold for profit by fans.

Starr, along with Bryan Cranston, Billie Eilish, Will Ferrell and bandmate Paul McCartney, are among the growing slew of globally renowned public figures who simply refuse to put pen to paper — even for the biggest fans. Although a quick trawl of the internet and social media platforms suggests that none of them exercise an equivalent ban on posing for selfies.

So, what does this mean for the humble autograph? And are we witnessing its decline and eventual extinction?

‘It’s true that selfies are more popular because they’re quicker to take. You need to be patient to get an autograph, it involves queuing up outside a stage door for example,’ says Valentina Borghi, head of autographs and memorabilia at Chiswick Auctions, one of the world’s leading auction houses for the inky flourishes of history’s most notable individuals. ‘Celebs seem to prefer them [selfies] as they don’t have to spend the same amount of time on them,’ Borghi adds. ‘But autographs still have their appeal.’

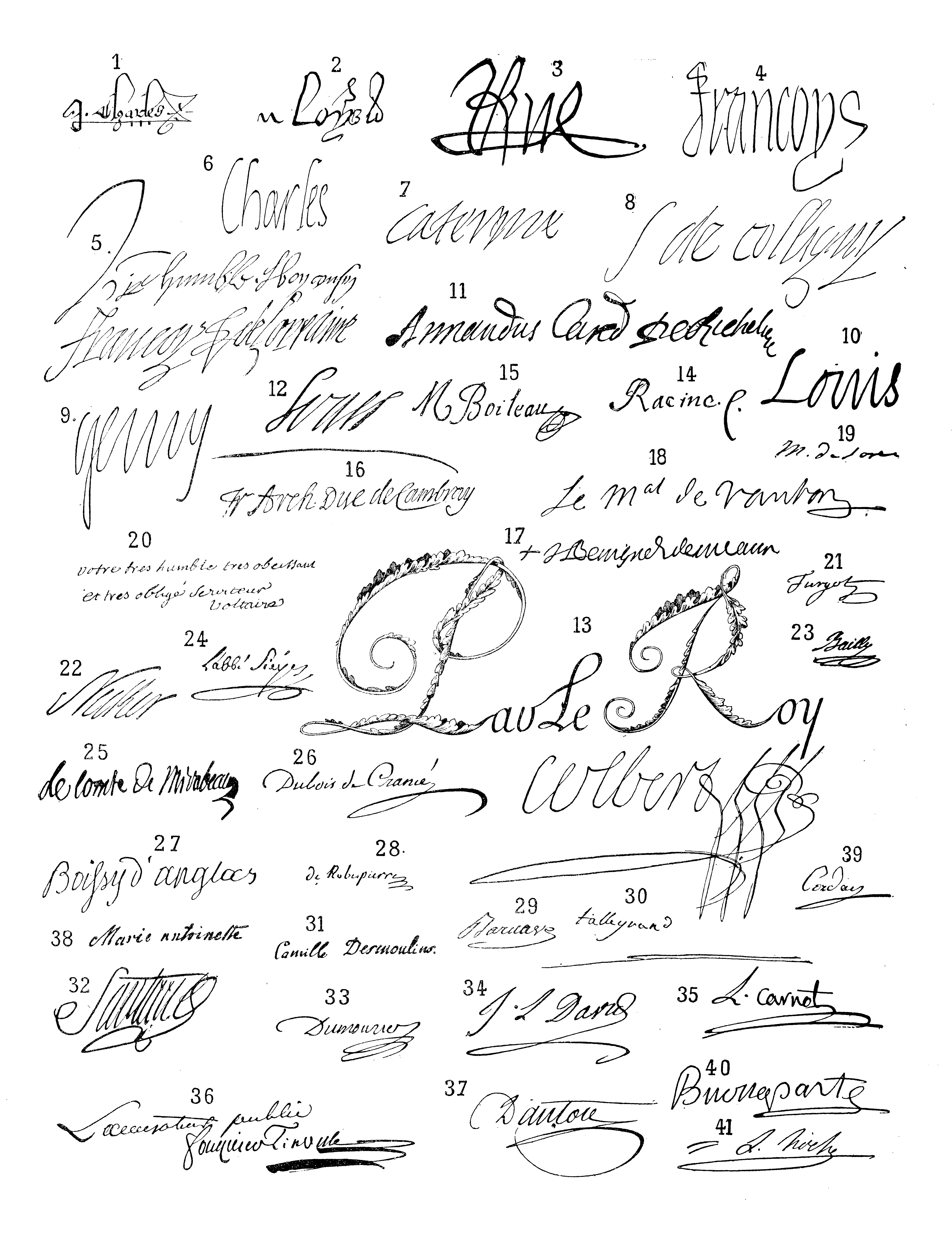

The official signatures of European leaders and royalty, including Napoleon Bonaparte (40).

Autograph collecting has been around for thousands of years. Pliny the Elder had a huge collection including, apparently, the signature of Julius Caesar. Sadly, nothing of this vintage is known to have survived, but a revival of sorts began in Renaissance-era Germany, or what was then the Holy Roman Empire, with the oldest known extant autograph books dating back to the mid-15th century. The autograph’s growing popularity coincides with rising literacy rates, but Borghi also believes that the beginnings of a deeper relationship a person has with their own signature, or another person’s, developed amid those Teutonic staples and scrolls. ‘If you sign something that has value — whether it be legal or sentimental — then your signature is a reflection of yourself. Most of us usually only sign something that really matters to you. And that’s why an autograph has a power that is irreplaceable. It’s something you can keep and pass on to further generations. It’s meant to last.’

The most valuable autographs were penned, inevitably, by individuals who aren’t around anymore to pose for pictures — though the autograph business is not nearly as straightforward as that. Forgeries have been around for as long as humans have been scrawling, but an equally sizable problem comes with printed signatures. These far precede the automated document signing software that’s now a part of our everyday lives. President John F. Kennedy, Queen Elizabeth II, Adolf Hitler and Sir Winston Churchill were all keen users of printed signatures which means that what may look like the genuine thing is actually worthless. ‘One of the most commonly forged autographs is Elvis Presley,’ reveals. Borghi. ‘His signature is tricky in many ways. It’s a tough one to spot if it’s a fake or not. If you get a few bits of his signature right then you can make a good looking fake. I need to check the pressure of the pen, the dots, if the capital “P” touches the “s” on “Elvis” and many other things. His signature also changed over time, too, so the context of when he signed it, or not, is important.’ Forgers, however, will go to extreme lengths to avoid being caught by the professionals, including going to the effort of sourcing a piece of paper manufactured by a Memphis-based paper company in the 1960s.

Another private, London-based autograph trader of three decades, who wishes to remain anonymous, told me that his job isn’t to destroy the dreams of people who believe they have come across a valuable autograph clearing out the attic of a deceased relative. ‘Selling forged autographs on the open market is, of course, illegal; for me to pass something off, knowingly or unknowingly as real when it isn't, would destroy my reputation,’ he admits. ‘But some people just don’t want to believe it. They become upset and say they’ll go to another auction house. That’s their prerogative, but they’ll only get told the same thing.’

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

‘Time is the great equaliser’ goes the saying, but when it comes to autographs it can wreak havoc, dramatically increasing, or decreasing, their value, depending on what, and who, is in vogue. A mere decade ago, autographs of Hollywood Golden Age actors from Clark Gable and Rudolph Valentino to John Wayne regularly fetched around £400-500 at auction houses around the world. In 2025, a paltry £150 (at least in comparison) is considered a good day.

‘Everything is being reviewed by modern parameters now,’ says Borghi. ‘Gone With The Wind was taken off a streaming platform not long ago because it was seen as depicting slavery in a condescending way. Modern collectors then think: “Clark Gable was in a movie that endorsed slavery” and, rightly or wrongly, his autograph loses value.’

However, there is an intriguing discrepancy between those who fail modern day tests of political correctness, and those who simply never let liberal concerns bother them in the first place — because while the signatures of supposedly non-liberal movie stars of yore haemorrhage in value, those of dictators and tyrants tend to hold steady. Today, an autographed photograph of Hitler would likely go to auction with an estimate of £4,000-5,000 — so would the signatures of Mao Zedong and Joseph Stalin. But is it ethically questionable for collectors to profit from the sale of autographs of men who caused so much suffering? ‘You can value an autograph without endorsing the person,’ says Borghi. ‘For better or worse, these people are part of our history.’

A post shared by The Prince and Princess of Wales (@princeandprincessofwales)

A photo posted by on

Today’s celebrities au fait with the fact that fans want photographs over autographs; even Taylor Swift, easily the most successful entertainer on the planet right now, has noticed a decline in fans brandishing pens and scraps of paper. ‘I haven’t been asked for my autograph since the iPhone with camera was invented,’ she wrote in the Wall Street Journal, back in 2014. ‘The only souvenir kids want [from me] these days is a selfie.’ Swift was surely one of the first to notice this seismic change in fan demands — a chance that appears to be strongly tied to the advancement to near ubiquity of social media. Put simply, when it comes to social media’s emphasis on close social proximity and users one-upmanship over rival accounts, posting a photo of a piece of paper with a scrawl on it just doesn’t pass muster or generate clicks. A captured photo hug with a superstar, however, ticks all the boxes Instagram requires: physical intimacy, the suggestion of conversation and friendship and photographic proof that, yes, this moment happened — and it happened to me.

Then again, even Swift, Starr and McCartney cannot compete with Martin Luther who definitely wasn’t ever around to be photographed. In 2016, Christie’s auctioned a letter signed by the German priest and theologian. Dating from 1523, the epistle, addressed to theologian Jacob Montanus and written in Latin, fetched £98,500. Compare this to the current value of the autographs of all four Beatles (around £4,000-5,000) on one page and it seems more likely that, should autograph hunting not go the way of quills and Box Brownies, it will be your descendants in the next, but three centuries who are most likely to benefit from your lengthy wait at the stage door of a theatre, convention hall, royal palace or gig venue. It all makes me feel rather relieved that I have never once asked for an autograph from any of the celebrities I’ve interviewed over the last two decades. I’m not immune to the odd photo though and have to admit that, on my phone, there are a few ‘hugger mugger’ snaps of me with notable names such as Priscilla Presley to Alexei Sayle. Clutching at photographs of myself with a celebrity who doesn’t know my names feels like a slightly pathetic way to bookend a life in journalism, but ultimately, it still feels a little more personal than clutching a ticket stub or a souvenir programme with a fading signature on it. The photo of me with Elvis’s wife may be valueless, but, on the other hand, Valentina Borghi has demonstrated, there aren’t life changing financial values to the signatures of most celebrities from the last century anyway — even the most venerated ones.

And yet the business of autograph collecting remains relatively healthy, suggesting that there is something beyond financial gain that lies behind the hobby; perhaps a more nebulous feeling that comes not with meeting a celebrity, but with cherishing something inky that they’ve left behind en route to their private jet or penthouse suite.

‘It’s amazing to see how people are still so keen to collect pieces of paper with signatures on them and exchange them online with other collectors,’ concludes. Borghi. ‘It’s all a little more niche now I think but autographs still have a huge power. It won’t die out anytime soon.’

Rob is a writer, broadcaster and playwright who lives in Brixton, South London. He regularly contributes to publications including the Daily Mail, Daily Telegraph and Conde Nast Traveller. Rob is the Special Correspondent for the BBC Radio Four programme Feedback and can also be heard on the From Our Own Correspondent programme on BBC Radio Four and the World Service. His first play, 'The Gaffer', premiered at the Underbelly Theatre as part of the Edinburgh Fringe in 2023.