The rise, fall, rise and eventual demolition of a Welsh wonder with an intriguing link to the Duke of Westminster

Melanie Bryan delves into the Country Life archives and the history of one of Wales’s most extraordinary manor houses.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The land on which Emral Hall once stood is recorded as being in the ownership of the Puleston family since the reign of Edward I until the 18th century — with one, brief exception in the early 15th century.

Various big houses were raised on the Welsh Marches plot, but the most recent and lasting incarnation dated back to the Jacobean, post-Civil War era. It had a magnificent, oak-panelled drawing room with the signs of the Zodiac carved into the ceiling — and was said to be among the finest, and most unusual, in the land.

The drawing room's carved ceiling also depicted Hercules's 12 labours.

Plenty of modifications were made to it over the years including the installation of carved oak wainscotting throughout the majority of the building, wrought iron entrance gates (said to be Caldecott’s inspiration for his illustrations for Washington Irving’s Bracebridge Hall) and a highly-unusual, wrought iron dog-gate at the top of the stairs.

Numerous tragedies befell the Puleston family, but none so dramatic as that of Captain John Puleston, the last male in the family line. He worshipped the anadrome of God more than the Lord himself and, in 1774, tore down Emral’s medieval chapel and fashioned some new kennels out of the remains. (He is also said to have repurposed the altar as an ironing board). John was dead within the year in what everyone at the time assumed to be an example of divine retribution. On the way back from a hunt he was thrown from his horse, and his head struck the aforementioned kennels on his way down.

However, Emral, officially untethered from the Pulestons for the first time in more than 500 years, went from strength to strength. The house and its lands went to the son of a female member of the family, Sir Richard Price, who immediately took the name and arms of his forebears. Sir Richard was firm friends with George IV, The Prince Regent, who was said to have become a frequent visitor to the ever-expanding property (as was his younger brother William IV). Some would say they all had a bit too much fun because Richard and his son racked up such huge debts that after they’d both died, no one wanted to take Emral on (the likely annoyed family member who ended up lumbered with it all but abandoned it and spent all of his time in London).

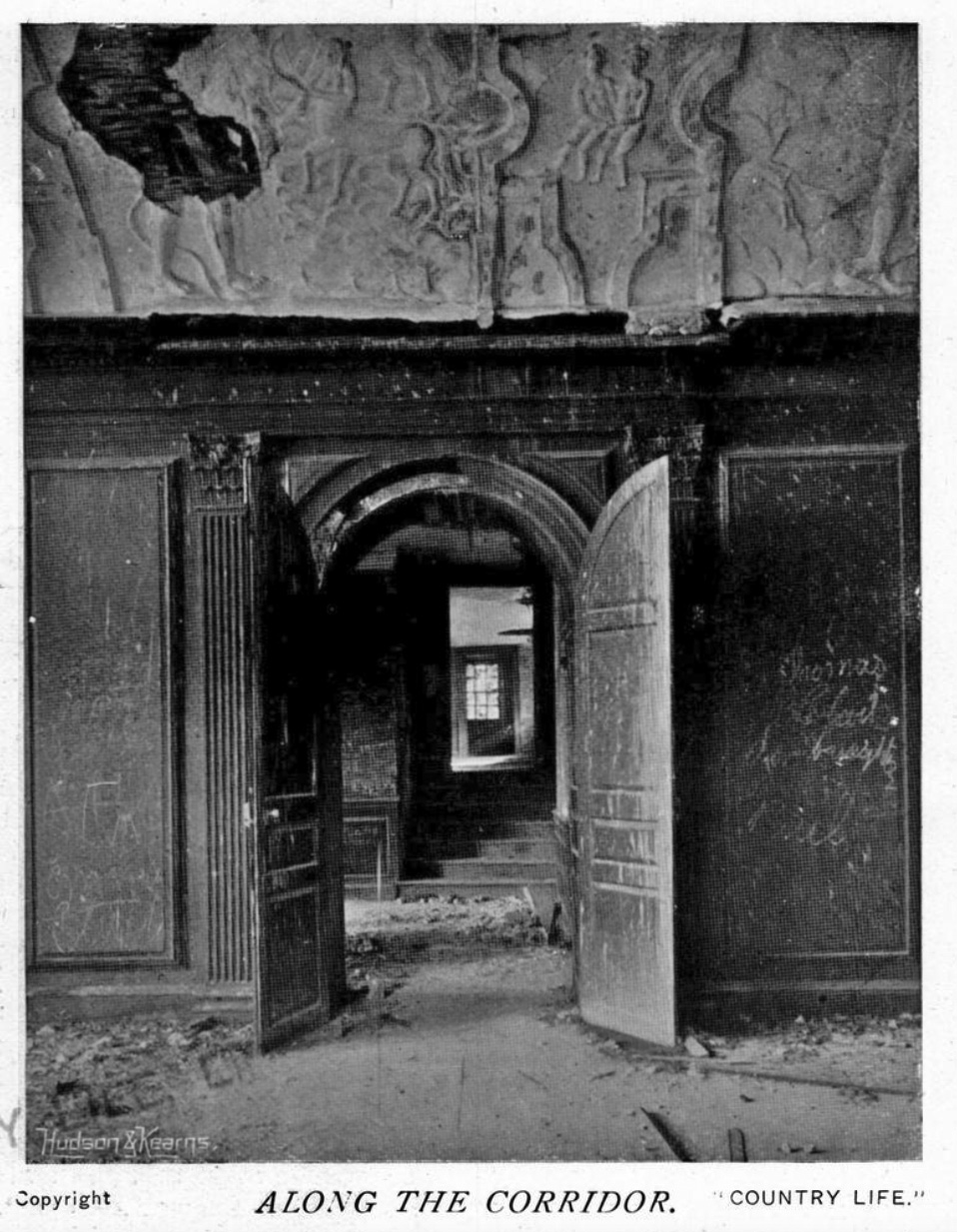

On December 4, 1897, Country Life published an article titled: ‘A State of Ruin’. The piece lamented the state of the moated manor house which, left empty, had been vandalised.

A photograph published in Country Life in 1897 clearly shows graffiti festooned on the oak panelling of the house. Note, also, the crumbling Jacobean plasterwork ceiling.

‘Any stray tripper could enjoy the much-valued privilege of breaking a pane of glass, removing a bit of woodwork and scribbling his name on the walls… Its once beautifully-painted staircase walls have lost all trace of the subjects of the decoration, and the banisters and rails of the black oak staircase have been kicked out and carried away, together with pieces of the oak carving, notably from the fireplace in the drawing room. The lofty panelling of this room is much disfigured with names and dates carved by unthinking visitors who used to visit the hall without permission, entering by broken windows, with evidently no object but spoliation.’

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

This being the tale of a house that rose and then fell and then rose again and then fell again and, well, you get the picture means that not everything was lost.

The Dowager Lady Puleston, the now-late third Sir Richard’s wife, was determined to resurrect the once-great Hall. She set to work with great gusto and with great success until 1904, when disaster struck. Again.

A bolt of lightning hit the chimney on the left wing of the house and fire spread quickly, destroying everything in its wake, including the servant’s quarters. Firefighters, who had come from as far away as Wrexham, battled the blaze in deeply inclement weather for hours.

In response, the Dowager Lady Puleston redoubled her efforts, the results of which were lauded in a 1910 edition of the magazine. Upon her death, Emral passed into the hands of a Mrs Summers who appears to have spent a large amount of her time hosting charitable events for nursing associations in the grounds. However, when she, too, passed, Emral Hall’s luck really was up.

Soon, the all-too familiar furniture sale and demolition notices started to appear in the local press. The famous Jacobean ceiling was ‘knocked down for £13’, the ‘Georgian oak panelling in the library for £32’ and ‘a fine old oak staircase with thirty-eight treads fetched £60’.

While it is not known where the staircase currently is, the ceiling was bought by Clough Williams-Ellis and re-erected at his ‘home for lost architecture’ (Portmeirion, in Wales). The gates were bought by the Duke of Westminster and stand, to this day, outside Eccleston Church in Cheshire.

The Country Life Image Archive contains more than 150,000 images documenting British culture and heritage, from 1897 to the present day. An additional 50,000 assets from the historic archive are scheduled to be added this year — with completion expected in Summer 2025. To search and purchase images directly from the Image Archive, please register here.

Melanie is a freelance picture editor and writer, and the former Archive Manager at Country Life magazine. She has worked for national and international publications and publishers all her life, covering news, politics, sport, features and everything in between, making her a force to be reckoned with at pub quizzes. She lives and works in rural Ryedale, North Yorkshire, where she enjoys nothing better than tootling around God’s Own County on her bicycle, and possibly, maybe, visiting one or two of the area’s numerous fine cafes and hostelries en route.