Helene Kröller-Müller: The woman who made van Gogh

After a life-threatening illness spurred Helene Kröller-Müller to make plans for a museum, she bought modern art voraciously, forming an extraordinary collection that shaped the early-20th-century perception of Vincent van Gogh

When the hammer fell on Vincent van Gogh’s Bridge at Arles (Pont de Langlois) on May 21, 1912, shock waves must have coursed through the auction house in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Closing at 16,000 guilders, the painting made more than five times its estimate.

Twenty-two years earlier, the troubled artist had shot himself in a field near Auvers, in France, thinking his art a failure. His posthumous reversal in fortune owes much to the woman behind the winning bid on that spring evening at the dawn of the 20th century: Helene Kröller-Müller.

Born in 1869 in Horst, Germany, to industrialist Wilhelm Müller and his wife, Emilie Neese, she had married in 1888 Dutchman Anton Kröller, who looked after the Rotterdam branch of her father’s business. A year later, Müller died and Kröller went on to manage the entire company, soon expanding into shipping. Despite their substantial wealth, neither he nor his wife showed particular interest in collecting painting or sculpture until 1905, when the 36-year-old Kröller-Müller, on the advice of her eldest daughter, started taking art-appreciation classes with critic Henk Bremmer.

Helene and her husband Anton.

'She decided that, should she survive, her collection would no longer be hers alone, but would, one day, be open to the public'

Bremmer was an early van Gogh scholar and consistently encouraged his students to buy works by the Dutch artist, who, despite a 1905 retrospective at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, remained underappreciated. With Bremmer’s guidance, Kröller-Müller began collecting modern art and, in 1908, acquired Edge of a wood, a work from van Gogh’s Dutch years, soon followed by Four sunflowers gone to seed, from the then more controversial French era. It marked the beginning of a lifelong fascination.

Kröller-Müller was still a fledgling collector when, in August 1911, a sudden shock filled her with new purpose. Diagnosed with a life-threatening condition, she had to undergo a major operation. Perhaps also influenced by an earlier visit to Florence in Italy and the artistic patronage of the Medici, she decided that, should she survive, her collection would no longer be hers alone, but would, one day, be open to the public.

As cultural historian Eva Rovers noted in a 2007 issue of Simiolus: Netherlands Quarterly for the History of Art, her ambition was at least partly driven by a need for social acceptance that, as a relatively nouveau riche, had thus far eluded her — she was determined to show ‘how a merchant family from the turn of the century contributed to inner refinement’.

Whatever her motives, there is no doubt the plans changed her approach to collecting. She switched to buying what she thought would ‘withstand the test of the future’ and she did so voraciously.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Four sunflowers at seed by van Gogh, acquired by Kröller-Müller in 1908

'She was determined to show "how a merchant family from the turn of the century contributed to inner refinement"'

With Bremmer acting as an agent — ‘He was my first minister and beside him I felt like a queen,’ she once said — Kröller-Müller went on a shopping spree in Paris in April 1912 and returned 115,000 guilders poorer, but with two paintings by Georges Seurat and Paul Signac and 15 by van Gogh, including Landscape with wheat sheaves and rising moon and La Berceuse. It was that trip that alerted other collectors to a rising appetite for the Dutch artist, leading, the following month, to the unexpectedly high bids for Bridge at Arles (Pont de Langlois).

Even then, however, interest in van Gogh remained far from universal. When, later in 1912, Kröller-Müller loaned some 38 of her pictures to Germany’s Sonderbund exhibition of modern art, she was by far the largest lender, vastly surpassing even the Dutch artist’s sister-in-law, Jo. It was the first of many loans, which progressed hand in hand with more acquisitions (of van Gogh alone, she bought two paintings from Jo and another 26, plus six drawings, at auction in 1920). As a result, as Dr Rovers highlighted in Simiolus, her collection shaped the artist’s image for years.

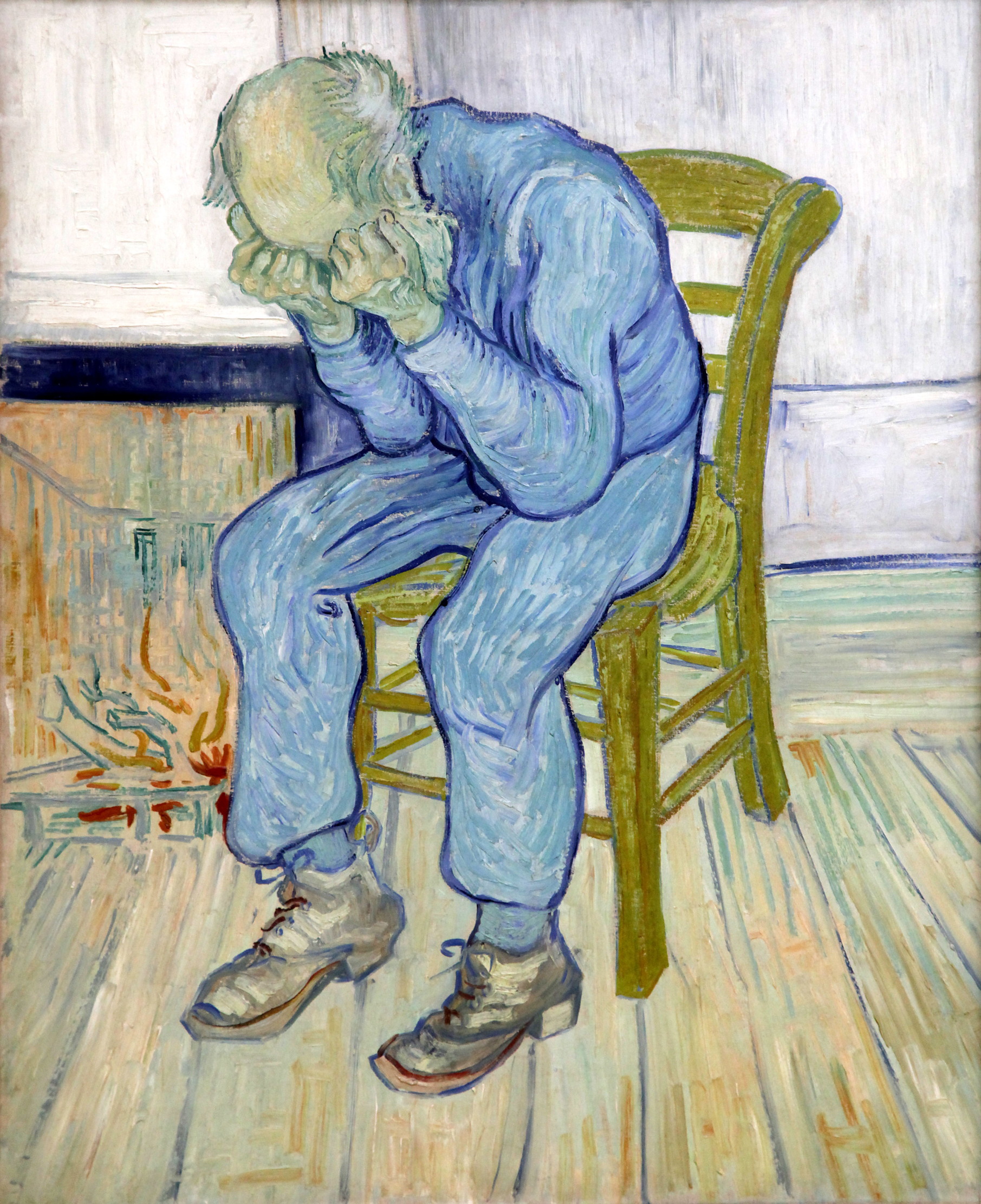

Over time, Kröller-Müller’s passion rubbed onto her husband. For their 25th wedding anniversary in 1913, he gave her a picture by Henri Fantin-Latour (Portrait of Eva Callimachi-Catargi) and another van Gogh, At eternity’s gate, which he had bought almost a year earlier and kept secret. She was delighted: ‘I could never have dreamed such a thing; even if you had given me the prettiest, largest, most expensive pearl necklace, I could not have been happier.’

At eternity's gate was purchased by Anton and presented to Helene as a gift in 1913.

However, it was in 1928 that Kröller really played a crucial role in shaping his wife’s collection: that summer, some 116 drawings by van Gogh went on show at a gallery in The Hague. Although destined to go under the hammer, they were also available to buy as a group for 100,000 guilders. Wary of spending so much money, Kröller-Müller sought to split the pictures and the expense with an American museum.

Her husband, however, took a different view. For all that he used to joke, when accompanying visitors from his offices to hers, that they were crossing ‘from the credit side to the debit side’, he immediately decided to buy the lot. It was an especially bold, or perhaps rash, move on his part, because, since the early 1920s, the family company had been beset by financial problems. This had not only curbed Kröller-Müller’s art purchases, but also put a spanner in her project to launch a museum, which had already been troubled by her difficult relationship with her architect, H. P. Berlage.

The prospects had looked up when the latter’s replacement, Henri van de Velde, was appointed in early 1920 to design a grand new building at the Kröllers’ country estate, De Hoge Veluwe: ‘Work began with the disregard for economy that had always characterised the family’s activities,’ wrote art historian Giles Waterfield in Country Life in 1981. ‘Special railway lines were constructed to bring 4,000 cubic metres of sandstone into the park, but then building stopped.’ Money had become short and, in 1922, a disconsolate Kröller-Müller wrote to her friend Sam van Deventer: ‘When I pass the site of the museum now, it feels like an open grave that awaits its corpse’. Yet, she persevered.

On April 26, 1935, the Kröller-Müllers donated her collection to the Dutch State and, in 1938, after many ups and downs, the Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller opened to the public, albeit in a much more modest, ‘temporary’ building than the one initially conceived by its patroness. It was just in time — Kröller-Müller, already too ill to give a speech on opening day, died a year later, on December 14, 1939. Ahead of the funeral, her coffin was laid out in the museum among her beloved van Goghs. Her dream, however, lived on and the building was expanded repeatedly after the Second World War.

As well as van Gogh, Helene collected works by neo-Impressionists such as Georges Seurat. His Le Chahut will be on show in the UK for the first time.

Although van Gogh formed the heart of the original Kröller-Müller collection, he was by no means the only artist represented in it. Over the decades, in a bid to show what she saw as the evolution of modern art from ‘realism’ to ‘idealism’, she also acquired works by artists ranging from Jean-François Millet to Piet Mondriaan.

Now, a selection of the museum’s neo-Impressionist paintings heads for the National Gallery, where it will be at the heart of a new exhibition, ‘Radical Harmony: Helene Kröller-Müller’s Neo-Impressionists’, which also includes loans from such institutions as the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, Museum Barberini Potsdam and Tate, as well as the National Gallery’s own collection.

Van Gogh is only represented by one picture, a version of The Sower, but there are Pointillists and post-Impressionists aplenty, whether bringing to life soothing seascapes (such as Signac's view of The Beacons, Saint-Briac, in Brittany) or exploring the harsh reality of life in the industrial age (Maximilien Luce's The Iron Foundry). On show for the first time in the UK will be Seurat’s painting of can-can dancers, Le Chahut, described by Waterfield as ‘a startling work in which the artist manipulates appearances to convey a mood of gaiety’.

Although perhaps not the show for those who find the 'dotty' approach of Pointillism a little repetitive, 'Radical Harmony' puts the Kröller-Müller collection in context — and helps shine the spotlight on the truly remarkable woman who gathered it.

Carla must be the only Italian that finds the English weather more congenial than her native country’s sunshine. An antique herself, she became Country Life’s Arts & Antiques editor in 2023 having previously covered, as a freelance journalist, heritage, conservation, history and property stories, for which she won a couple of awards. Her musical taste has never evolved past Puccini and she spends most of her time immersed in any century before the 20th.