'You have to work hand in hand with the author — like a dancer has to work with the music': Illustrating Homer's epic poems

Artist Clive Hicks-Jenkins, faced with the colossal challenge of illustrating Homer's 'The Iliad' and 'The Odyssey', eschewed grandstand views of monumental battles, looking instead for what he calls the little cracks in the paving stones.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Nothing lights the fire in Clive Hicks-Jenkins’s eyes like a good epic. ‘The moment you give me a narrative, I’m off like a rocket,’ he says, as a huge grin splits his face. Two years ago, the Welsh artist worked on Seamus Heaney’s translation of Beowulf for The Folio Society. Now, he has completed an even more colossal project for the same publisher: illustrating Homer.

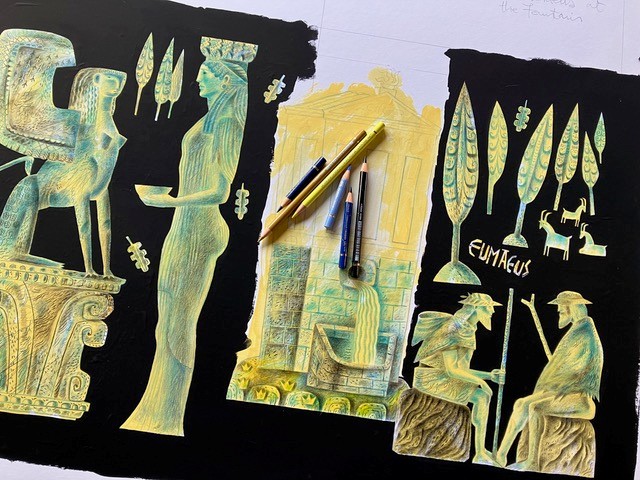

When the society first approached him about tackling the work of the Greek poet, Clive simply enquired: ‘Which one?’ He was thrilled, if perhaps a little daunted, to discover it would be both The Iliad and The Odyssey. Even better, it turned out he would be illustrating Emily Wilson’s translations, which he had much enjoyed, because he found they brought a fresh perspective to what had previously been a male preserve. He headed straight to his books and started re-reading them — The Iliad twice and The Odyssey, with which he was more familiar, once — albeit not before a brief jaunt to the British Museum to look at earthenware vases from ancient Greece. ‘And then I got to work and made a cast list.’

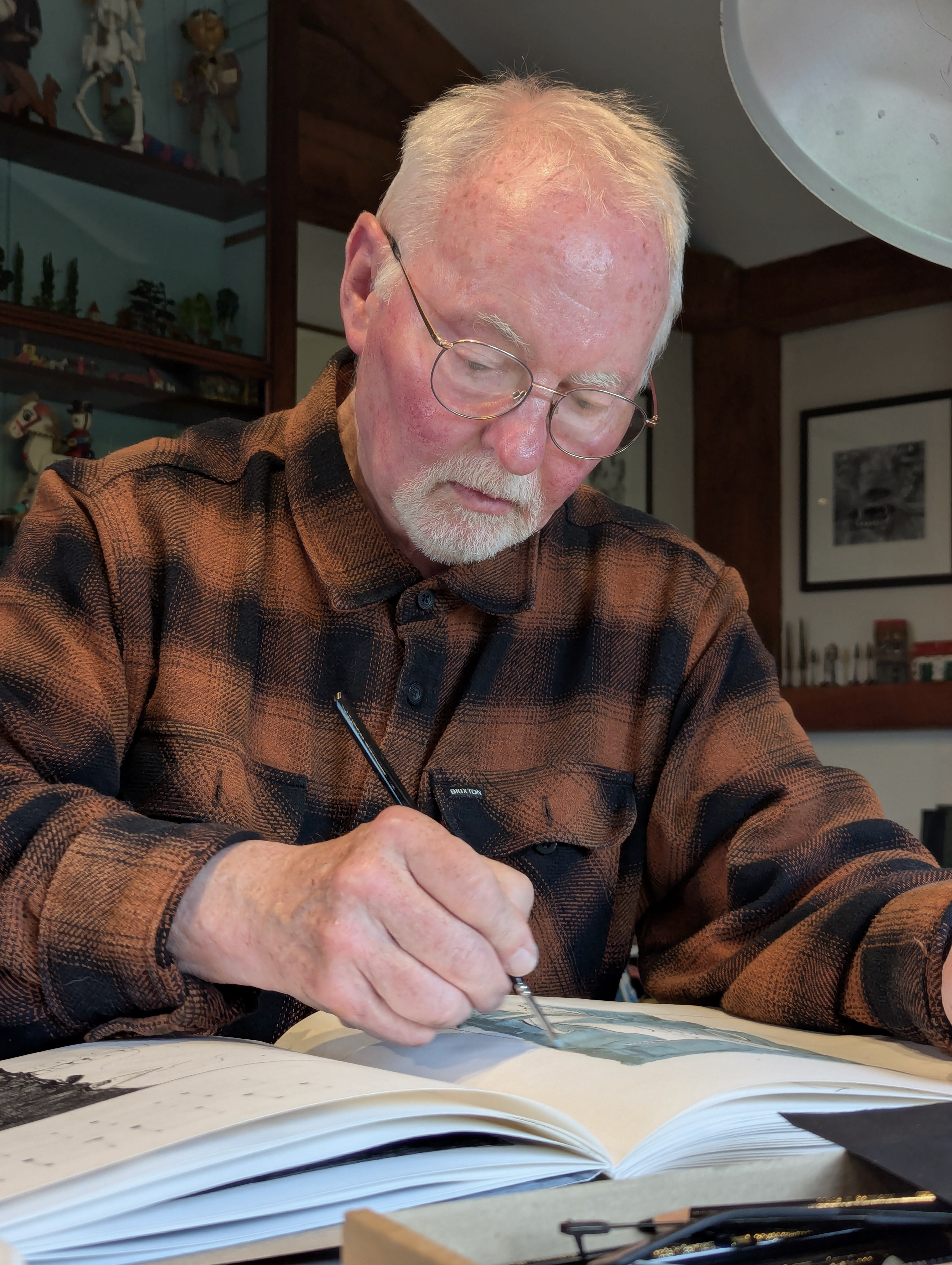

This might seem an odd starting point, but Clive (above) had long worked in the theatre before making a career switch in his forties. Although he had been so passionate about art as a child that his friends and family thought he would grow up to be a painter, he enrolled in a vocational school, becoming a choreographer and stage director, after a spell as a dancer. However, theatre is unforgiving: ‘I was always on planes, always in new cities and I got tired of it. It’s terribly lonely. You go from one job to another to another and you pour yourself into it. It’s a young man’s game, a young woman’s game.’ Having decided on a change, he went back to Wales: ‘I didn’t think: “Oh, I’ll become an artist.” I just took a breather. I returned to my great love of poetry and began to draw. Drawing evolved into painting.’ Still, he admits, he probably wouldn’t have had the courage to pursue it professionally had it not been for his husband, historian and curator Peter Wakelin, whom he met a little more than 30 years ago. ‘He said, “You’re actually very good at this; you should go further.” He took my work to a gallery and I sat outside in the car trembling.’

He has since had more success as an artist and illustrator than he had ever imagined, but in those early, hesitant days, he used to hide his theatrical background: ‘I thought that I’d be poorly judged for that: a parvenu, a jack of all trades.’ As his reputation grew, however, keeping quiet about his performing-arts past became increasingly difficult — until one day he realised: ‘I wouldn’t be as good at this if I hadn’t had that career before. I can absolutely see how, as a director and choreographer in the theatre, I’ve brought that into my work as an artist, because I am a narrative painter. Whether I’m painting a huge Annunciation, or illustrating The Iliad and The Odyssey, I’m telling stories that fit into frames. That’s what you do in the theatre. You have a frame, which is the proscenium arch, and everything is placed into that. So it’s not at all surprising to me that I do a casting at the beginning of a project like this. I don’t know where else you would start other than to make a cast list and say: “Okay, which of you is in and which of you is out.”’

With two complex books such as The Iliad and The Odyssey, the cast list ‘was like this,’ he gestures, opening his arms wide, and threw up some surprises: ‘Looking at The Iliad, you’d think perhaps Achilles would be the principal character, but the character who appears more than anyone else is the goddess Athena. I didn’t plan it that way. It just happened because she threads through both books, moving the chess pieces.’ A stitch in that thread particularly enthralled him: ‘There’s a wonderful scene in The Iliad, where she harnesses her chariot with Hera, queen of the goddesses, and they go off to battle. That idea of Athena and Hera together, a little like Boudicca and her daughters going to battle against Rome — I loved that.’

In 'The Illiad' Hector dies when Achilles spears him in the throat.

What makes the real difference in Clive's work is not only his choice of characters and scenes, but how he approaches them. Illustration, he explains, is all too often dismissed as a mere reproduction of words in pictures: ‘That’s not my job,’ he counters. A natural storyteller — ‘If you spoke to Peter, he would say: “You come to me if you want the facts. If you want a story, go to Clive, because he’ll embroider it”’ — he prefers to create images that feel like ‘little cracks between paving stones. I don’t want to illustrate the paving stones. They don’t need it. You’re looking for little entries in the text between them. I want the illustrations to be a breath between the words, like reciting poetry and giving you a moment to take in what’s been said. The image is that moment of thought’. One of his favourite ‘cracks’ is a scene from The Odyssey in which Odysseus goes on a nocturnal expedition and struggles to find his way: ‘The goddess Athena sends a night heron to guide him. It captured my imagination and I did a double-page illustration that has the heron in the foreground, because it is so poetic that a heron sent by a goddess should do this work of guiding [men] through the darkness.’

Not for Clive the ‘obvious’ grand-stand views of monumental battles. Even in perhaps The Iliad’s most famous passage, where Achilles defiles the slain Hector, dragging the corpse behind his chariot three times around the tomb of Patroclus, he chose the unexpected, the subtle detail: ‘It would be easy to over-egg the image and to have the horses and the chariot and the trampling; instead, I did a real close up of Hector’s torso with his legs drawn up and his perforated heels — a detail to meditate on, rather than what you might do in cinema, which would be to pull back and see the whole.’

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

If anything, he continues, delving into his theatrical past, illustration is more like dance: ‘I love cinema, but with cinema, you can take a story and do anything with it, whereas with a book, you have to work hand in hand with the author — like a dancer has to work with the music.’ A ‘dance’ of which he has fond memories is the collaboration with Poet Laureate Simon Armitage. ‘I had the manuscripts as they were being written. That’s terribly exciting, because you’re watching it unfolding and, although you’re wary of the fact that something might change, by the time you get the final, approved manuscript, you’re like an actor who’s learned all his lines. I don’t need the manuscript anymore, because I’ve lived it, breathed it, slept it.’

There is a flipside to this syntony with the written word: he could never illustrate a book he didn’t like or understand. ‘I always want to have a conversation with the writer, dead or alive.’

Carla must be the only Italian that finds the English weather more congenial than her native country’s sunshine. An antique herself, she became Country Life’s Arts & Antiques editor in 2023 having previously covered, as a freelance journalist, heritage, conservation, history and property stories, for which she won a couple of awards. Her musical taste has never evolved past Puccini and she spends most of her time immersed in any century before the 20th.