Inside the remarkable restoration of King George III's observatory

Commissioned by George III, the observatory has a long and fascinating history as a seat of scientific endeavour. It has now been restored as a home, as William Aslet reports.

On June 3, 1769, George III waited at the Kew Observatory for Venus to begin making its slow passage across the face of the sun. Nine others were present when contact was finally made between the planet and the edge of the solar disc, Queen Charlotte and the observatory’s superintendent Stephen Demainbray among them. According to Demainbray, the King ‘was the first who saw’ the phenomenon, beating, perhaps unsurprisingly, all others present to the observation by ‘half a second’. When contact was made, a bell was rung, summoning upstairs other guests in the observatory, including Princes Ernest and George of Mecklenberg-Strelitz. The Kew observatory had been built specially to witness this celestial event, having been commissioned from Sir William Chambers the previous year. The room in which they were all gathered — or, rather, packed tightly together — was a small, domical space at its top.

George III was the first King of England to have received a proper scientific education; Demainbray had been his tutor as a young man. The observatory’s construction, possibly funded by a gift made by his mother, is a mark of the seriousness of his interest in science. It also speaks to a broader moment of collective scientific endeavour. The transit of Venus was no event of purely astronomical curiosity. Measuring this rare phenomenon, which takes place at intervals of roughly a century, allowed astronomers to calculate the size of the Solar System and princes, astronomers and explorers all over Europe set out to measure it. Catherine the Great was one and Capt James Cook was another. His 1768 expedition to witness it from the southern hemisphere took him to Tahiti, 10,000 miles away from Richmond, and was funded by the King to the tune of £4,000.

Recently, it was used as a filming location in the Netflix series Queen Charlotte — the Bridgerton spin off that charts George III's relationship with the aforementioned. It was also advertised by Country Life a couple of years ago. The Observatory stands today in the middle of the Royal Mid-Surrey Golf Club and, following an impressive campaign of restoration, has now been turned into a private residence. Handsome and unshowy on the exterior, in line with George III’s personal tastes, it is an astylar rectangular block, three window bays deep to the sides and five on the fronts, the middle three of which are canted. Architectural historian John Harris has compared it to garden buildings by Chambers, such as the ‘Casine’ he designed for Thomas, Lord Bruce at Tanfield, North Yorkshire.

The stuccoed exterior of the restored Observatory, designed by William Chambers, surmounted by its telescope dome.

James Fleet in the observatory as the old King George III in 'Queen Charlotte'.

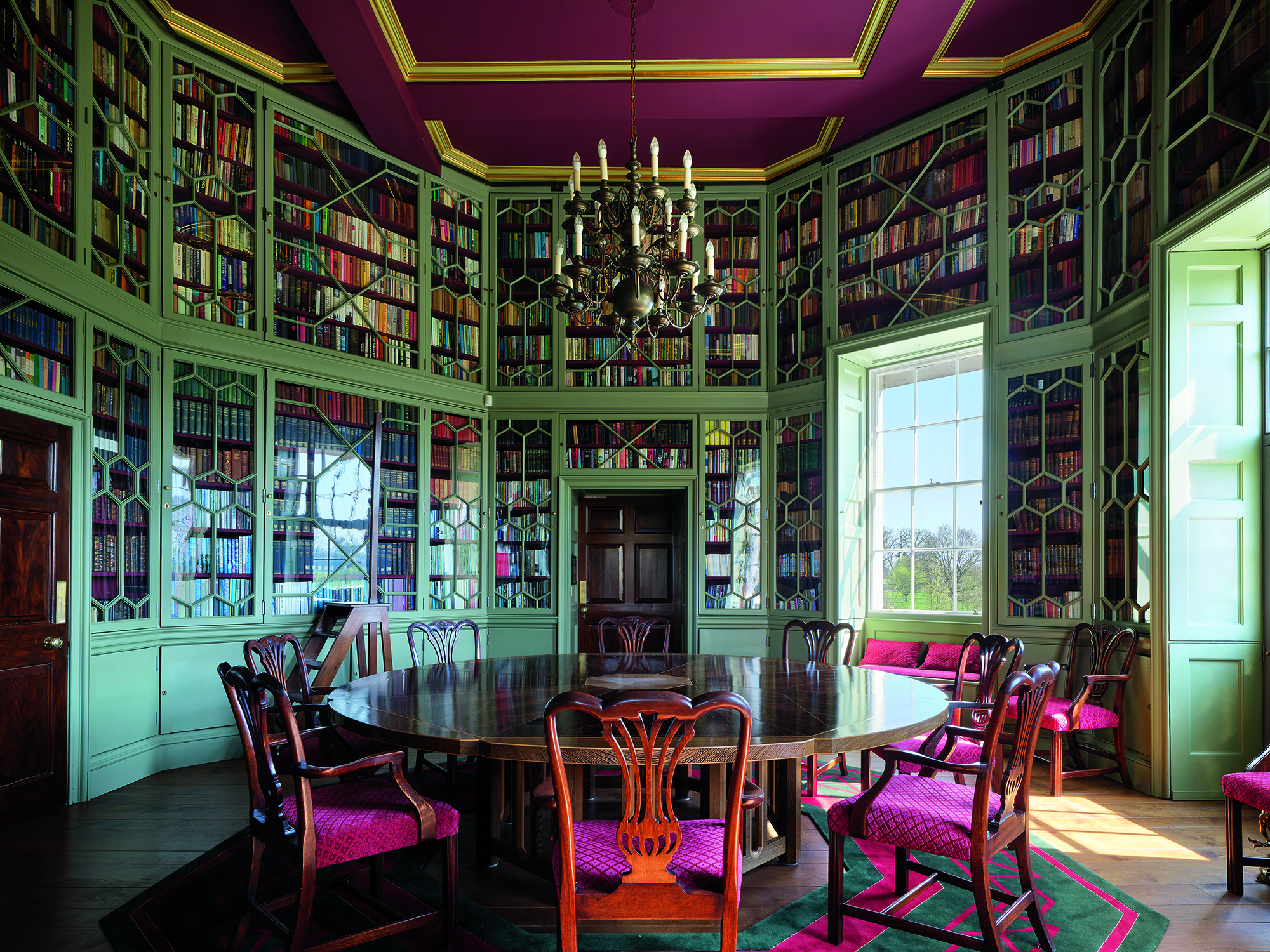

As first built, the attic storey of the Observatory only projected above the canted bays, making them stand out more prominently, an effect that is somewhat reminiscent of the nearby Asgill House, designed by Sir Robert Taylor about 1760. This was obscured in 1888 and 1892, when the east and then west wings were raised respectively, meaning that the attic now runs continuously around it. Internally, the canted bays on the north and south façades create two octagonal rooms, which are installed with floor-to-ceiling Chinoiserie cabinets, the work of joiner James Arrow. These impressive examples of Georgian carpentry were originally used to store George III’s collection of rare minerals and scientific instruments.

Kew Observatory’s undemonstrative Palladian façades belie the fact that it was at the cutting edge of Georgian technology. The oldest surviving example of its type in the world, it was also apparently the first observatory to include a revolving dome with a removable cover, a feature that is familiar to us from observatory design today. Amazingly, the mechanical apparatus that enables this to function still exists in situ, in full working order. Before this, no major observatory had been built in England since Sir Christopher Wren’s in Greenwich, so Chambers probably took advice from Demainbray in forming the design. He must also have made use of connections in his native Sweden. Harris noted that, for many years, Chambers had known Baron Carl Hårleman, the architect of two recent Swedish observatories. Of them, the one at Uppsala, built for Anders Celsius in 1740, is the obvious prototype. Added onto an earlier medieval building, it was really a house with an observatory on the roof. This superimposition of an observation room onto a squarish plan was repeated at Kew.

The King loved the Observatory. He considered adding to it, commissioning a ‘weather register’ for the park from James Adam that would, in architectural historian David Watkin’s view, have been a building of ‘exceptional elegance’. It was never begun, however. Possibly with the exception of William IV, George’s children cared little for astronomy and, in 1840, Queen Victoria relinquished the palace at Kew to form the botanical gardens there. Being no longer near a royal residence, therefore, the Observatory was vacated the following year and George III’s collection of optical instruments and minerals, which until then had remained there, was dispersed. Many of the objects went to the Armagh Observatory in Northern Ireland, part of Archbishop Robinson’s Enlightenment city and King’s College, London (parts of the collection owned by King’s are now on long-term loan to the Science Museum, London).

The revolving telescope dome with removable cover, which was at the cutting edge of 18th-century technology. Its mechanism is still fully operational.

The dining room, with its wallpaper taken from a 1772 port scene of Hong Kong.

The arrival of the British Association for the Advancement of Science (BAAS) at the Observatory in 1842 marked a decisive shift in its purpose. The BAAS sought to turn it into a ‘physical observatory’, where atmospheric conditions, geomagnetism, and other phenomena could be studied, as well as astronomy. Almost immediately, its outward appearance began to change. A 16ft-long copper conducting rod was installed to facilitate studies of atmospheric electricity, protruding from the dome’s roof like a gigantic antenna. The range of experiments carried out at the Observatory in these years was ambitious and involved the installation of some pioneering new technologies, foremost of which was the heliograph of 1856, the first piece of scientific apparatus ever designed to photograph the sun. At the same time, the observatory began to specialise in the testing of scientific instruments. This required the construction in 1854 of the first of the two so-called ‘magnetic huts’ that can still be seen just outside the Observatory. Although they look like simple sheds, these huts are remarkable structures that had to be built entirely out of wood due to the risk of geomagnetical interference posed by metal components.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

By 1870s, however, the BAAS was finding it increasingly difficult to cover the Observatory’s operating costs. As a result, it was taken over by the Royal Society in 1871. In the years that followed, the society continued building on its reputation as a centre for the standardisation of scientific instruments. This culminated in 1877 with the introduction of the ‘KO’ mark, a brand guaranteeing that an instrument had been studied and tested at Kew. This entailed a considerable expansion of the Observatory’s output. An 1890 Richmond guidebook estimated that ‘something like 10,000’ instruments were being tested there every year. In response to this intense activity, modifications began to be made to the fabric of the building itself, the most immediately visible of which was the heightening of the attic storey.

The Royal Society itself gave way to the National Physical Laboratory (NPL) in 1900, a body that was founded further to improve the standardisation of scientific tools. The NPL’s tenure was brief, however, as its plans to expand the site met with local opposition, causing it to move into new premises in Bushy, west of Hampton Court, that were given by Queen Victoria. In 1910, therefore, the Observatory’s occupant changed yet again, with the Meteorological (Met) Office now moving in.

The Met’s arrival was outwardly signalled by the installation in 1912 of a 40ft-high anemometer, which occupied the Observatory for the next 70 years. During this period, the site continued to be at the forefront of meteorological research, work that took on a vital importance during the Second World War. It was a former Superintendent of the Observatory, Group Capt James Stagg, who advised Gen Eisenhower to postpone the D-Day Landings due to his correct forecasting of unfavourable weather.

The drawing room, with its new cornice and royal coat of arms.

One of the octagonal rooms, with its cases displaying a porcelain collection. The gallery is a 20th-century insertion by the Met Office, tenant from 1910 until the 1970s.

By the 1970s, shortly after its bicentenary, the Observatory was outgrowing its utility to the Met Office. New facilities had been built elsewhere, and, in spite the establishment of the Royal Mid-Surrey Golf Club in 1892, which helped maintain the insulation of the site, the encroachment of suburbia, as well as the development of Heathrow Airport, meant that it was no longer a viable place for research. The last observations there were made in 1980 and, the following year, it was put on the market, when it was bought by its present owner, Robbie Brothers, a Hong Kong-based businessman. He then leased it to a car-repair company, which remained headquartered there until 2011, when it returned to Brothers.

Work began in 2014 on transforming the Observatory into the private residence that it is today. Although intact in its essentials, the building’s repeated changes of function had left it much altered. Internally, the most keenly felt loss was of Chambers’s original cornicing, neither drawings or photographs of which are known to survive. The setting of the Observatory, moreover, had been greatly marred by the cluttering addition of administrative blocks that had accumulated during its time as an office building. The recent restoration, which was completed in 2019, sought to undo as many of these changes as possible, stepping in to fill gaps imaginatively where the historical record fell short. Not seeking faithfully to recreate George III’s Observatory — an impossibility in view of the absence of any contemporary plans — the restoration rather sought to impart to the building a convincing 18th-century flavour.

In this, it has greatly succeeded. Walking into the Observatory, it is hard to imagine that this was once a busy office building. Traces remain, but you need to know where to look. In the first of the two octagonal rooms at either side of the building, for instance, there is a mezzanine level, inserted during Met Office days. This has been maintained to make better use of the original display cases, which now show the present owner’s collection of porcelain. In the dining room, space that was created by 20th-century partitioning was used to introduce a dumb waiter. As with the drawing room at the other wing of the house, this room effectively had to be created from scratch. This was done by the addition of period-accurate cornicing throughout, painted in matte olive green with gold highlights.

At the same time, imaginative modern-day features were added, such as the beautifully carved George III coat of arms in the drawing room, the work of sculptor Clunie Fetton. The most striking of these by far is the Chinoiserie-style wallpaper in the dining room. Instead of showing birds or foliage, as would be the case in genuine 18th-century examples, the wallpaper is a scaled-up copy of a 1772 ‘port scene’ showing the Hong Kong trading outposts of different European countries, a reference to the present owner’s adoptive home. Painted by hand in a workshop in Wuxi, China, by Fromental, this spirited variation on a Georgian theme took about 5,000 hours to complete.

Perhaps the most successful of all these recent innovations has been the landscaping of the surroundings. Visiting today, the observatory seems to stand in an untouched piece of Georgian parkland. This was exactly the intention. Overseen by the multi-award-winning landscape architect Kim Wilkie, the design took on recommendations from the Thames Landscape Strategy, which seeks to restore lines of sight to Richmond that were opened by Capability Brown in 1764, but have since been closed. These sightlines bring us back to George III, for one of the most important of them that has now been restored is towards the two 18th-century obelisks that stand in the park. These marked the meridian line that was used in 1769 for the calibration of the King’s astronomical instruments, and subsequently to set the clocks of government offices. The reopening of this view is a fitting tribute to George III’s love of science.