Scone Palace: The Seat of the Earl of Mansfield and Mansfield, part 1 by John Cornforth

From the Country Life Archive: Little remains of the medieval abbey of Scone, just north of Perth, where the Kings of Scotland were anointed, but the origins of the present Regency Gothick house seem to lie in the partly early 17th century house built by the 1st Viscount Stormont. John Cornforth reports. Originally published in Country Life, August 11, 1988.

RETURN TO THE SCOTTISH CASTLES HOMEPAGE

There are two distinct strands to the history of Scone, one that is entirely Scottish and rich in legends, and another that is both Scottish and English. The first is concerned with its ancient history, as an Augustinian abbey and the place where the Kings of Scotland came to be enthroned and hold assemblies. It was here that Macbeth is supposed to have bled to death and where Robert the Bruce was crowned. The second revolves round the history of the Murrays, Lords of Scone since they were granted it by James VI in 1604. He also created them Viscounts Stormont, and at the end of the 18th century they inherited the two English Earldoms of Mansfield.

Fig 1. The west front of Scone Palace.

Since Edward I removed the Stone of Scone to Westminster Abbey in 1296, and the abbey was sacked by a mob in 1559, there is now little visual evidence to suggest the palace's great antiquity, and its special role in the intertwining of Scottish history and tradition. On the other hand, there is an indefinable air of historic mystery about the place, particularly in the vicinity of the chapel on the mound; and enough remains from the period of Sir David Murray of Gospertie, the 1st Lord of Scone and Lord Stormont, to seem to tie the two together. Moreover, the earlier history has obviously influenced later members of his family in their attitude to the place.

Scone Palace in its present form was designed by an English architect, William Atkinson, for the 3rd Earl of Mansfield in the years after 1802 (Fig 1). But, as with so many country houses, it is a much older and more complex structure than might be guessed today; and in that it reflects the downs as well as the ups of family history.

The 18th century history is particularly unexpected, and without the complementary achievements of the 7th Viscount Stormont (1727-96) and his uncle William, 1st Earl of Mansfield, Scone could never have existed in its present form. So this first article is largely devoted to them, whereas the second will cover the building activities of the 3rd Earl.

Fig 2. The Jacobean south and east fronts in the late 18th century. Lord Scone probably planned the house for his own use and for the reception of future kings coming to Scone for their anointing.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The earliest view of Scone is Slezer's engraving of about 1700 that shows it none too clearly from the east, with the long east range and two buildings standing in front, one presumably the old gateway (Fig 3), and the village huddled close up to it. If that is compared with a series of late 18th century watercolours (Fig 2) and Andrew Cock's survey, the palace is seen to have consisted of two principal ranges, facing south and east. Behind them were a complete north court and an incomplete south court that grew up at different and unknown stages.

What is difficult to decide is whether the two main ranges were built on to earlier building round what became the north court, or whether they were part of an ambitious scheme that was never finished. No dates survive on the building, but the conjunction of its gables, the form of the family pew in New Scone church, which bears the arms of David, Lord Scone and his wife and the date 1618, Lord Scone's great monument in the chapel on the Moot Hill (Figs 5 and 6), beside the palace, and the carved stones embedded in the chapel walls with his initials and the date 1618, suggest that it was probably he who built the two main ranges about that time.

The exceptional feature of the house must have been the Long Gallery in the east range, which had a painted ceiling, presumably on the scale of that at Earlshall, and similar in detail of handling to the work at Stobhall and St Mary's Church, Grandtully, in the same county.

Fig 3. The east front framed in the arch of the early 17th century gatehouse.

Apparently the earliest full account of the house is that written by John Loveday in 1732: "The old Gate-way has CR on it: beyond ye Court that opens into, is another Court enter'd also by a Gate...In ye 2d Court to ye left is an unroofd Row of Cloisters. The Rooms are handsome, wainscotted with Oak, & have fret-work Cielings. The Chimney-pieces are of very elegant workmanship in different kinds of Marble, excellently carv'd...The Gallery is a fine Room, has a bow'd Cieling of Wood, painted with Miniatures of Stag-hunting, prospects etc. There are several Rooms within another; in one of 'em a dark Purple Velvet Bed work'd by Mary Q of Scots; in ye same Room are Needlework Hangings done by Nuns."

Beyond the Long Gallery, at the south-east corner of the house lay what

in the late 18th century was called the King's Room. Thus it is probably

not too fanciful to suggest that Lord Scone planned his house both for

his own use and for the reception of future kings coming to Scone for

their anointing. Charles I, however, never had a Scottish coronation,

but Charles II was crowned at Scone in 1651.

Loveday's reference to the bed hangings by Mary Queen of Scots and the needlework hangings by nuns is particularly interesting, because it not only suggests that the bed hangings now in the Duke of Lennox's Room have always been at Scone, but that the same may be true of the panel of late 16th century needlework in the same room (Fig 4). Margaret Swain recognised this as being of Justice and Peace Embracing, copied from an engraving by Jean Wierix after Martin de Vos and published about 1574 (see The Burlington Magazine, May 1977).

Fig 4. Justice and Peace Embracing: a panel of late 16th century needlework probably always at Scone.

To find such things at Scone helps to give an idea of its early character, complementing both the family pew in the church at New Scone, and Lord Scone's great monument sent north from London by Maximilian Colt in 1618-19 and for which he charged £280. Colt is best known for his work at Hatfield, but this towering structure with its knights in armour that seem to have stepped out of an early Inigo Jones masque is virtually unknown.

On the monument Lord Scone explained the special remainders attaching to the descent of the property, but the line only became established 27 years after his death with the succession in 1658 of the 4th Viscount Stormont. The family's means continued to be far from secure, because both the 5th and the 6th Viscounts were loyal to the Stuart cause, in turn receiving the Old and the Young Pretenders at Scone in 1715 and 1745. Both had to go into exile, as did the 6th Viscount's brother, James, who was created Earl of Dunbar in 1720-21 by the Old Pretender and died in Avignon in 1770.

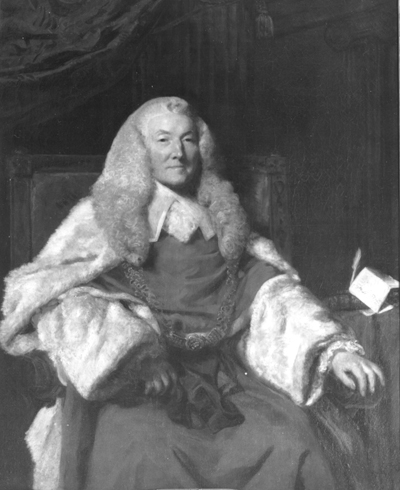

In that generation loyalties were divided, and William, the third son, who was born at Scone in 1705, was sent to Westminster and then on to Oxford. Whether that was deliberate hedge-betting is unclear, but it opened the way to a brilliant and materially successful career in the law in England and to the advancement of the family honours and fortune. Made a baron in 1756, when he became Lord Chief Justice, and an earl in 1776, William Mansfield is a familiar grand figure from his portraits by Reynolds (Fig 10) and Martin, and in architectural circles he is remembered for his patronage of his fellow Scot, Robert Adam, at Kenwood.

Fig 5. A detail of the monument to Lord Scone in the chapel, made by Maximilian Colt in 1618-19 for £280.

Although he was unquestionably loyal to the Hanoverians, he also remained loyal to his family, and it was he who supported his nephew David, who succeeded his father as 7th Viscount Stormont in 1748. Like his uncle, the future Lord Stormont had been sent to Westminster, and as soon as he left Oxford he went abroad for five years, supported by loans from his uncle.

William Mansfield and his wife, Lady Elizabeth Hatton (Fig 11), had no children, but her few surviving letters to her nephew suggest the liveliness and closeness of their relationship. For instance, when her husband was first made a peer in 1756, she wrote to her nephew: "tho Im now at the fagg end of the Peerage, and by being so, have lost the Pas of many No one can rejoice more than I do that your Uncle Admist all the confusions etc is now gott safely into Port or rather If you please into the Haven where I have long Earnestly wish'd him to be. The Title is dolce, the Mottoes bien choisis and the Promotion Universally applauded what more to wish but that he may very long live to enjoy a Post which he already fills with so much dignity".

Early the following January she wrote: "Money certainly burns in your Pocket to lay it so out as you have lately done in purchasing Dresden China for me were you within reach of hearing (which by the way I am very very sorry you are not) you would not fail having a good scold, but as that unfortunately is not now the case I return you many thanks for that which you must allow me to call an Unnecessary token of remembrance."

Fig 6. Lord Scone's monument is virtually unknown. The figures in armour seem to have stepped out of an early Inigo Jones masque.

Presumably it had been partly thanks to his uncle's influence that Lord

Stormont was attached to the Paris embassy in 1751 and then appointed

ambassador to Dresden in 1755; just as it was thanks to his financial

support that he was able to take up the post. That was the start of a

career almost as brilliant as his uncle's. His first embassy was

followed by his appointment to Vienna from 1763 to 1772, and to Paris

from 1772 to 1778. When Frederick the Great invaded Saxony, Lord

Stormont followed the Elector when he retreated to his Polish kingdom,

and in Warsaw he met and in 1759 married a pretty widow, Henrietta

Frederica,Grafin von Lunan, a Saxon by birth who had been married to a

Dane, Frederick Berregaard. In the private rooms at Scone hang a

charming pair of portraits of them by an artist hardly known in Britain,

Marcello Bacciarelli, who was born in Rome in 1731, went into the

service of Augustus III in Dresden, followed him to Warsaw and died

there in 1818 (Figs 7 and 8).

Sadly, Lady Stormont died in Vienna in 1766. It was in an attempt to get over his loss that Lord Stormont went to Italy in 1768, where he met Wincklemann, who was deeply impressed by his learning, and sat to Batoni for the portrait now at Scone. In 1766 he married the Hon. Louisa Cathcart, one of the daughters of the 9th Lord Cathcart, who looks unfairly grim in Romney's portrait at Scone, as can be gathered from the remarks of contemporaries and from the chatty letters (in E. Maxstone Graham's The Beautiful Mrs Graham (1927)) that she sent to her older sisters, the Duchess of Atholl and Mrs Graham of Balnagown.

It was not easy for a 20-year-old girl to marry a man nearly 20 years older and find herself the wife of the British Ambassador to Louis XVI. When she arrived in Paris, Madame du Deffand, who had become a friend of Lord Stormont, wrote that she "is pretty, she holds herself badly, and has not a charming manner, but her expression is full of intelligence". None of the published letters suggest that she and Lord Stormont were other than happy, but fairly soon after his death she married a life-long admirer, Robert Fulke Greville.

Figs 7 and 8. The 7th Viscount Stormont and his first wife. The portraits were painted by Marcello Bacciarelli in Warsaw in 1759, soon after the Stormonts' marriage. Stormont was ambassador to the Elector of Saxony, who had retreated to his Polish kingdom.

Lord Stormont's diplomatic career inevitably limited his visits to Scotland, and on one in 1773 he wrote that the house at Scone "can never be made a tolerable habitation without immense expense which it can never deserve. I shall never think of more than keeping it from ruin". The following year, however, his wife gave birth to a son, so not unnaturally his attitude began to change, and in 1778 his wife was anxious to make the house habitable - "at least I think very seriously of making it so".

He consulted George Paterson, the Edinburgh architect, but his first scheme was too ambitious, and more modest works were done under his direction over the next few years, while Thomas White gave advice about the setting of the house. By 1783 "the whole of Mr Paterson's plan is finished and it is a very convenient Habitation". From the factor's letters and inventories compiled in 1785 and 1790, and from the survey made after Lord Stormont's death by Andrew Cock, it is possible to get quite a clear idea of the character of the place. Also, it is possible to recognise a number of things still in the house, among them his diplomatic perquisites, the versions of the state portraits of George III and Queen Charlotte, and by the two canopies of state that in the usual way he had made up into a state bed (Fig 9). However, there was no unnecessary expenditure, and the state bed, for instance, was given curtains of moreen rather than damask.

That he sent those relics of his diplomatic life to Scotland suggests that he viewed Scone as the family seat, but it must have been less fashionably furnished than his London house in Portland Place or his uncle's house at Kenwood. There are at Scone pieces of French furniture and porcelain that could well have belonged to him. Also, there is some fine English marquetry furniture that probably came from Kenwood, but could conceivably have belonged to him rather than his uncle, including a pair of card tables in the Ambassador's Room now attributed to Cobb and a pair of commodes in the private rooms.

Fig 9. The state bed. It is made out of two of the canopies of state that were diplomatic perquisites of Lord Stormont.

Lord Stormont had always been regarded as his uncle's heir, and, when the latter was created Earl of Mansfield in 1776, there was a special remainder whereby the title would go to Lord Stormont's wife in her own right and then to her heirs, because it was wrongly believed at the time that a Scottish peer could not take an English peerage other than through inheritance. Opinions changed later, and in 1792 Lord Mansfield was given a second Earldom with remainder to his nephew.

So when he died in 1793, Lord and Lady Stormont inherited his two titles, and since Louisa, Countess of Mansfield, outlived her son, it was only after her death in 1843 that they both devolved on their grandson. That explains why the present Lord Mansfield as well as being 14th Viscount Stormont is 8th Earl of Mansfield in Nottinghamshire and 7th Earl of Mansfield in Middlesex, two places that were intentionally unScottish to 18th century English ears.

In the chapel at Scone beside the great monument to the 1st Lord of Scone is a suitably elegant but unsigned neo-Classical monument to the 7th Viscount's Saxon wife, which serves for his heart as well. But his uncle is buried in Westminster Abbey, not so far from the Stone of Scone. Over his monument, for which the money had been provided by an anonymous admirer, Lord Stormont sought the advice of his wife's uncle, Sir William Hamilton, who on May 21, 1793, recommended that Flaxman should do it: "I believe that can be no doubt that the Venetian Canova whose name your Lordship could not recollect is the first sculptor in the World but as your Lordship seems to think it necessary that the monument should be executed by a British Artist, I recommend without hesitation John Flaxman who in my opinion is the best artist that Great Britain has ever produced, and who has more natural genius than Canova, but has not yet produced any work so near to Greek perfection as Canova has."

Figs 10 and 11. The 1st Earl and Countess of Mansfield, by Sir Joshua Reynolds. Lord Mansfied had a brilliant legal career in England, rising to become Lord Chief Justice and amassing a substantial fortune.

"Was I to offer my opinion I would give the commission to Flaxman and as he is on the point of returning to England I would make him finish the model at Rome, where he will be able to do it better in the midst of so many fine pieces of Grecian Sculpture and where there are many more judicious eyes to criticise than in London...Believe me My Dear Lord-Nolikins, Bacon and Banks are children in comparison of Flaxman."

The following year Sir William wrote again: "Some time ago I received a print of the late Earl of Mansfield whose memory I shall ever revere as I really think he was, all in all, the greatest man of the age in which it has been my lot to live." The commission, as Margaret Whinney pointed out, was the turning point in Flaxman's career, for it finally established his reputation as a sculptor. The model was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1797 and the monument was completed in 1801.

If Sir William makes a surprising appearance in the history of the Murrays, Lady Hamilton makes an even more surprising one in that one of her trustees was the 3rd Earl of Mansfield, the builder of the present palace.

Photographs by Alex Starkey. If you are interested in additional images of this property, please contact the Country Life Picture Library.

RETURN TO THE SCOTTISH CASTLES HOMEPAGE

BALMORAL CASTLE: A HIGHLAND PARADISE BY MARY MIERS (FREE PDF DOWNLOAD)

BLAIR CASTLE: THE SEAT OF THE DUKES OF ATHOLL, PART 1 BY ARTHUR OSWALD

CRAIGIEVAR CASTLE: THE SEAT OF SIR JOHN FORBES, BART., NOW LORD SEMPILL BY PETER GRAHAM

CULZEAN CASTLE: THE SEAT OF THE MARQUESS OF AILSA, PART 1 BY ARTHUR T. BOLTON

EILEAN DONAN CASTLE: THE PROPERTY OF THE CONCHRA CHARITABLE TRUST BY ANTONY WOODWARD

GLAMIS CASTLE: THE SEAT OF THE EARL OF STRATHMORE, PART 1 BY OLIVER HILL

HOLYROODHOUSE: SCOTLAND'S ROYAL PALACE BY SIMON THURLEY (FREE PDF DOWNLOAD)

STIRLING CASTLE: RENAISSANCE OF A ROYAL PALACE BY JOHN GOODALL

Agnes has worked for Country Life in various guises — across print, digital and specialist editorial projects — before finally finding her spiritual home on the Features Desk. A graduate of Central St. Martins College of Art & Design she has worked on luxury titles including GQ and Wallpaper* and has written for Condé Nast Contract Publishing, Horse & Hound, Esquire and The Independent on Sunday. She is currently writing a book about dogs, due to be published by Rizzoli New York in September 2025.