The real rock stars: Meet the makers of the Olympic curling stones

One of the most remarkable players in the Winter Olympics, Kays Scotland’s curling stones are both objets d’art and serious bits of sporting kit

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

'A curling stone slides across the ice with a lovely rumble,’ observes Jen Dodds. ‘The noise when it strikes another stone is wonderful — a satisfying, deep thunk’.

Jen won Winter Olympics gold in Beijing in 2022 with the GB women’s curling team and was beginning the defence of that crown in Cortina, Italy, at the time of going to press. At both Games, the 34-year-old from Edinburgh has used curling stones made by Kays Scotland, a small firm of dedicated craftspeople in Mauchline, Ayrshire, and the last remaining maker of curling stones in the British Isles.

‘Each stone is handcrafted,’ reveals Jim English, managing director of Kays. ‘Two types of granite are used. The outer stone, which includes the striking bands [the part of the stone that makes the clunk], is fashioned from common green granite. Common green has an elasticity that means it can absorb heavy blows.’ Blue hone granite is the insert that forms the running edge, the surface that comes in contact with the ice (and the bit that provides the rumble). ‘Blue hone is incredibly fine, which makes it water resistant,’ he continues. ‘It doesn’t draw in moisture, so it’s superb for sliding across the ice.’

'Each stone has its own unique character. A big part of the skill in curling is figuring out the personality of the stone — some curve more than others, some don’t travel so far or so fast. No two stones are the same'

John Brown of Kays Scotland hand prepares curling stones in Mauchline, Ayrshire.

Kays granite comes from a special source, Ailsa Craig, that mysterious 60-million-year-old ‘fairy rock’ that pokes up from the Firth of Clyde. Kays was granted the rights to harvest the island’s unique rock by the Marquess of Ailsa, whose family has owned the uninhabited island since 1560. It’s also a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) and home to great colonies of seals and seabirds. As a result, blasting is prohibited and granite can only be harvested sporadically.

‘Because of the breeding habits of the wildlife, we’re only allowed to go over in October and November,’ Jim points out. ‘Which, in terms of the weather, is not ideal, as you can imagine. It’s 10 miles out to sea and the rock faces we quarry from are a long way from the landing area. The common green comes from the south face of the island and the blue hone from the north. It’s a laborious process.’

However, the damp, cold and perilous work is worth it. Kays collects about 3,000 tons on each voyage, enough to keep the firm, which makes 150 stones a month, going for 10 years. ‘The granite from Ailsa Craig is like no other on Earth,’ Jim says. ‘Its unique properties make it almost impervious to freezing temperatures and to hard knocks, too.’ It’s almost as if it was designed to be made into curling stones.

'During Covid, the stones for Beijing were flown over in a private jet. This time, however, they went by lorry'

The stones are fashioned in what was once a snuffbox factory, a building to which Kays relocated from the company’s original watermill-powered workshops on the banks of the Ayr in 1911. Making them involves more than 20 processes and ‘a lot of physics’, but the most important input is the expertise of the workforce. ‘We’ve been honing our techniques here for 150 years,’ he continues. The technical aspect of making the stones is not the only consideration. ‘We’re very conscious of the aesthetics — the different colours and markings of the stone,’ Jim says. The result of this careful appraisal is a product that is not only a piece of sporting equipment, but an object of rare and refined beauty.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Kays of Scotland first started making curling stones in 1851. By then, curling as a sporting pastime was already more than three centuries old. Stirling Smith Museum in Dumbarton has curling stones that date from 1511 and the first recorded match took place at Paisley Abbey, Renfrewshire, in the winter of 1541. This most Scottish of sports reached its zenith in Britain during the 1870s, its popularity fuelled by the migration of Scottish tradesmen and a string of unusually harsh winters.

Today, dedicated curling facilities in England are few and far between. However, Historical Curling Places, a website devoted to recording the curling ponds of Britain, has confirmed records of more than 2,000 ponds where matches took place, including examples as far south as Brighton and Chichester in Sussex.

By the last decades of the 19th century, curling was so popular Kays had half a dozen competitors. Stones were made from a poetic panoply of rock: Burnocks, Tinkernhills, Carsphairn Red, Crawfordjohns, Blantyre Blacks. However, following the closure of Bonspiel in Deganwy, North Wales in 1990 — which used red and blue trefor quarried in the Llyn Peninsula — only Kays, with its common green and blue hone, remains.

Originally an outdoor sport, curling moved gradually undercover after the opening of the first indoor rink in Glasgow in 1907 and the fashion for country-house curling ponds faded. Today, the majority have long been abandoned, although the curling houses or pavilions where once the stones, brushes and other kit were stored often survive. Most resemble small tennis or cricket pavilions, although some were built in more elaborate styles and now pass for follies. The most celebrated example of the latter is the playfully elegant Thomson Tower in Duddingston, east of Edinburgh, designed by the city’s fêted neo-Classical architect William Henry Playfair in 1826.

Despite the sport falling out of favour south of the border, curling remains highly popular in Scotland, with more than 550 clubs boasting some 10,000 members. Kays supplies many clubs with stones, yet still exports close to 95% of production — not only to the global curling powerhouses of Canada, the US, Norway, Sweden and Japan, but also to less likely spots, such as Nigeria, Angola and Mongolia.

The stones are hand polished, as they have been for centuries. They weigh just under 40lb and sell for £800 each. It’s a sound long-term investment. ‘Our stones should last between 20–25 years, depending on the amount of use, and we offer restoration and servicing,’ explains Jim. ‘The running surface gets worn by friction, so needs to be re-grooved, and the striking band takes a lot of heavy knocks and needs to be re-ground every 10 years or so.’

Thomson's Tower in Duddingston, near Edinburgh, is one of the more ornate curling pavilions.

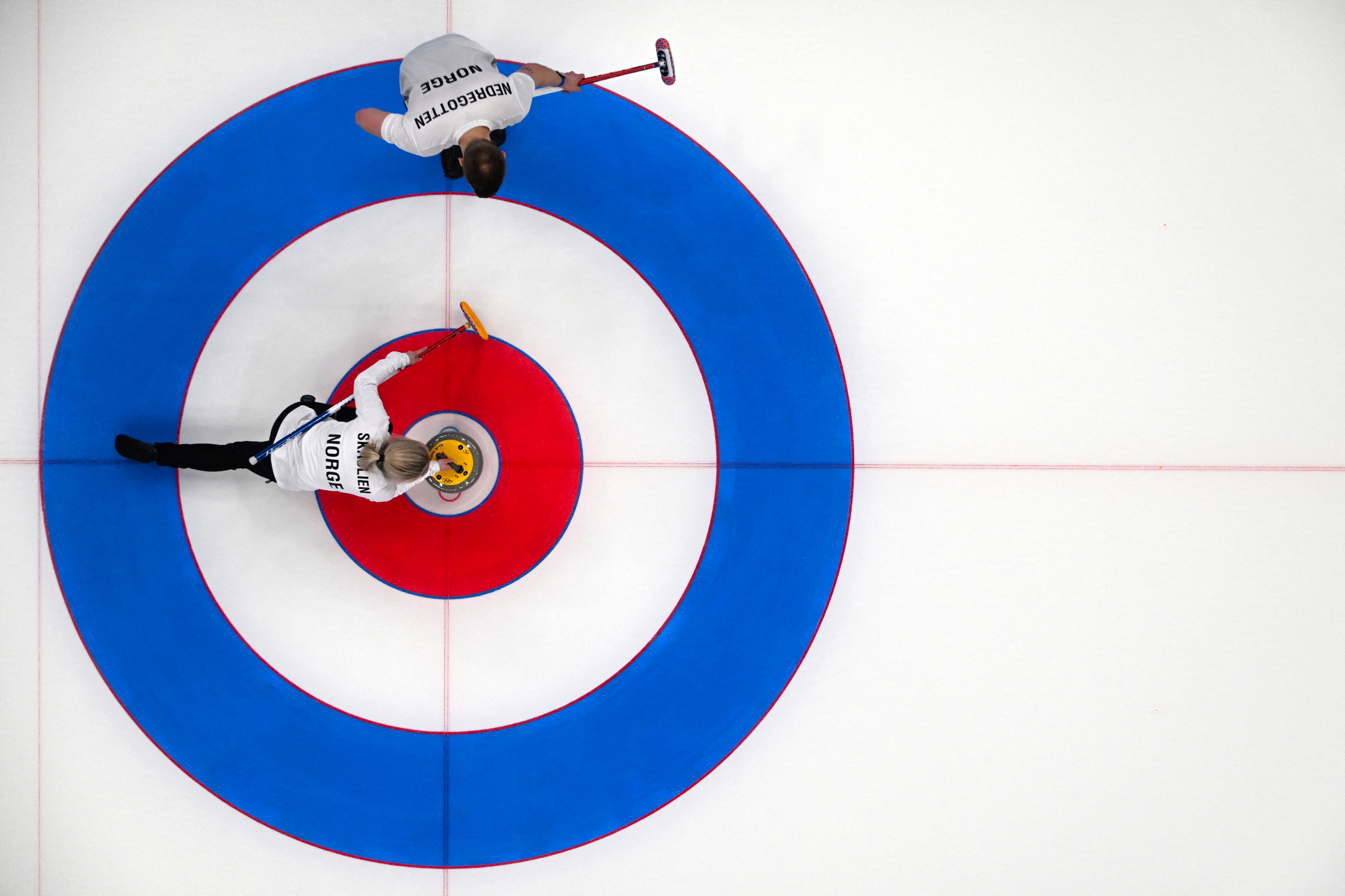

In curling competitions, pairs or teams of four each slide two stones (sometimes called rocks) towards the target — four concentric rings on the ice — which is known as ‘the house’. The curve or curl of the stone comes from the slow spin that is imparted on it as it leaves the hand. The feverish brushing temporarily melts the surface of the ice, altering the speed and curve of the stone — the quality of the rock is paramount. To the untrained eye, Kays curling stones may look uniform, but that appearance is deceptive.

‘The granite is made from about 15 different minerals,’ Jen reveals. ‘Each stone has its own unique character. A big part of the skill in curling is figuring out the personality of the stone — some curve more than others, some don’t travel so far or so fast. No two stones are the same. They slide differently, bounce off each other in distinct ways.’

Each stone made by Kays is individually numbered, which can help. ‘The numbers aid you with the history of the stone,’ she continues. ‘At the European Championships, for example, the same set of stones has been used several times, so you get to know each number, but characteristics are often changed by use — the stones are rubbed with sandpaper during competition and that affects how they behave. You’re always trying to work them out.’

Jen has been attempting to defend her Olympic title with Team GB in Italy. ‘Let’s say I’m keeping my fingers crossed,’ she admits. Meanwhile, the presence of Kays of Scotland’s curling stones at the Winter Olympiad is guaranteed. The company’s curling stones were used at the first Winter Games in Chamonix in 1924 and, since 2006, Kays has been the sole supplier of curling stones to the event. The 128 stones it made for the 2026 Games are now in use in Italy.

During Covid, the stones for Beijing were flown over in a private jet. This time, however, they went by lorry.

Harry Pearson is a journalist and author who has twice won the MCC/Cricket Society Book of the Year Prize and has been runner-up for both the William Hill Sports Book of the Year and Thomas Cook/Daily Telegraph Travel Book of the Year.