70 years of style: The clothes of Queen Elizabeth II

Far from being a passive dresser, The Queen pays close attention to what she wears and what those clothes convey. She has left a lasting impression on the fashion industry, believes Justine Picardie.

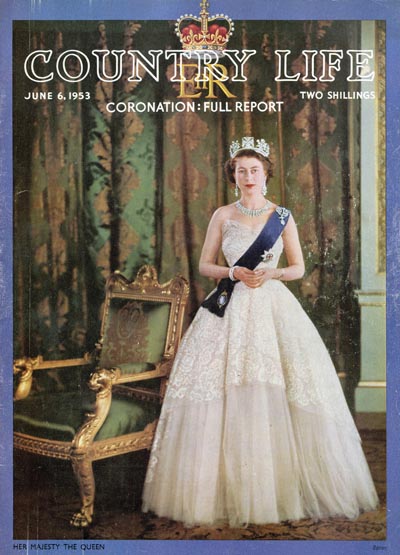

The Queen once said of herself, ‘I have to be seen to be believed’, which is why the iconography of what she wears is such an integral element of her enduring success. Her Majesty’s distinctive wardrobe performed a vital role in conveying a powerful visual message, making her instantly recognisable during a lifetime of constant public scrutiny. In doing so, The Queen never followed fashion, but created her own unique style, embodying majesty, modesty, mystery and myth.

All this took place during a tumultuous era, over which the representation of royalty evolved from highly controlled portraiture to instantaneous digital imagery, capable of being shared around the world in a split second. Yet from the moment the then Princess Elizabeth became heir to the throne, at the time of her uncle’s abdication in 1936, it was clear that her parents understood the importance of re-establishing a pictorial sense of stability and consistency.

Following Edward VIII’s momentous decision to marry the twice-divorced Wallis Simpson, the new King and Queen would evoke a more traditional era in their sartorial choices, both for themselves and their daughters. In contrast to the hard-edged Modernist chic of Simpson’s attire by Schiaparelli and other fashionable Paris couturiers, the young princesses and their mother wore matching outfits in gentle, feminine colours.

Indeed, George VI specifically asked The Queen’s favoured designer, Norman Hartnell, to evoke the decorative dresses in the royal portraits by 19th-century Court artist Franz Xaver Winterhalter. ‘His Majesty made it clear in his quiet way that I should attempt to capture this picturesque grace,’ wrote Hartnell in his memoir, recalling his tour of Buckingham Palace with the King.

Amid the Second World War, the Royal Family continued to look reassuringly traditional: the dignified King in his military uniform, as his wife and daughters adhered to the same restrictions dictated by clothes rationing as the rest of the country. The principle of shared duty, throughout the challenging years of national adversity, was emphasised when Princess Elizabeth was photographed in her uniform, as a trainee mechanic and driver in the Auxiliary Territorial Service.

Patriotism remained to the fore in the design of her wedding gown when she married Prince Philip in November 1947. It was deemed imperative that Hartnell should source suitably British fabrics (duchesse satin from the Scottish firm of Winterthur, near Dunfermline, with an ivory tulle train made from silk produced at Lullingstone Castle in Kent). After the ugliness of war, and continuing austerity, the public’s desire for optimism was reflected in the fairytale romance of Princess Elizabeth’s bridal dress, embellished with thousands of pearls and crystal beads and embroidered with a pattern of white York roses.

The Queen’s coronation gown, also designed by Hartnell, called for similarly detailed symbolism and meticulous attention to detail. The plan was to include all the emblems of Her Majesty’s realm: the English Tudor rose, the Scottish thistle, the Irish shamrock, and the Welsh daffodil. But to Hartnell’s alarm, he was instructed by the senior heraldic authority — the Garter King of Arms — that the correct emblem for Wales was, in fact, a leek. Despite Hartnell’s best attempts to highlight the daffodil’s greater beauty, the Garter remained adamant. The loyal couturier confessed in his memoir to feeling disheartened, but nevertheless followed his brief: ‘In the end, by using lovely silks and sprinkling it with the dew of diamonds, we were able to transform the earthy leek into a vision of Cinderella charm.’

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

There was one feature that Hartnell added in secret: a lucky four-leaf clover, embroidered amid the cluster of shamrocks. He later admitted having done so in the hope that The Queen might ‘touch this small omen of good fortune. This [she] did as she finally tried on her sumptuous gown and gently caressed the spreading skirt’.

Hartnell’s superb designs for The Queen continued to incorporate meaningful motifs, which contributed to their magical appeal. Take, for example, the dress that she wore in Ottawa for the centennial celebrations of the Confederation of Canada, on July 1, 1967: a royal-blue skirt and white bodice, with an exquisitely beaded band of silver maple leaves (the national emblem of Canada). It was one of the gowns displayed at Buckingham Palace in 2016, in an exhibition of The Queen’s wardrobe, ‘Fashioning a Reign’. Like everything else in that magnificent show, its timelessness is such that it would look as appropriate if worn today as it did half a century ago.

Also in that show — and equally memorable — was the primrose-yellow silk ensemble created by Hartnell for The Queen to wear at the Investiture of The Prince of Wales at Caernarvon Castle in 1969. The outfit comprised a coat, embroidered with pearls at the neckline and hem, worn over a sleeveless tunic and matching shift dress of the same material. When I spoke to Caroline de Guitaut, curator of the exhibition (and now Deputy Surveyor of The Queen’s Works of Art), she shared my admiration of it.

‘It’s beautiful,’ she agreed. ‘The Queen is one of the few people who can wear yellow. These clothes are stylish, but also have to follow protocol — they have to perform a role.’ A worldwide audience of 500 million saw the ceremony on television and the bold colour ensured The Queen was immediately identifiable, as did her striking, Tudor-inspired hat, by a favourite milliner, Simone Mirman, in the same yellow silk. The hat allowed her face to be seen and the discreet layers kept her warm. Thus pageantry met practicality, on this and every other occasion.

Hartnell’s success was matched by that of his contemporary, Hardy Amies, The Queen’s other key designer from the 1950s onwards. For all their competitiveness, both were masters of their art, avoiding the trap of creating anything too overtly fashionable, which would swiftly become dated. As Amies observed in his memoir: ‘Style is so much more satisfactory than chic. Style has heart and respects the past; chic, on the other hand, is ruthless and lives entirely for the present.’

The timeless quality of The Queen’s style was evident when her granddaughter Princess Beatrice married in July 2020 in an enchanting gown designed by Hartnell six decades previously. (The Queen had worn it on various occasions, most notably to the 1962 premiere of Lawrence of Arabia.) It was altered for the Princess by The Queen’s later dressmaker, Stewart Parvin, who created the emerald outfit Her Majesty wore to Ireland in 2011, and Angela Kelly, also a trusted confidante and friend.

It is the latter who ensured The Queen remains at the forefront of confident power-dressing in her nineties, with an emphasis on vibrant block colours (including tangerine, lime and raspberry pink), signature Launer handbags and coordinating hats.

But for me, The Queen’s authentic style was as apparent in her more private self: the clothes she wore as a countrywoman, with her dogs and horses. Certainly, those tweed and tartan skirts, sturdy shoes, riding jodhpurs and silk head scarves have been as influential on contemporary fashion designers — including Miuccia Prada — as Her Majesty’s grandest ball gowns and dazzling tiaras. Therein lies yet another of The Queen’s achievements: proving charisma need not fade with age and that true beauty can be found in quiet dignity.

Justine Picardie is a fashion writer, biographer and novelist, and a former editor-in-chief of Harper's Bazaar. This article was originally published in Country Life in June 2022.

Her Majesty The Queen dies aged 96

Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II has died at the age of 96.

Thank you, ma’am — we’ll miss you

We pay tribute to Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, who died on Thursday 8 September, aged 96.

Windsor Castle's rainbow to the heavens, and the other indelible images from the day Her Majesty The Queen died

The State Funeral of Queen Elizabeth II: The tale of the final farewell to Her Majesty

Details and images of the funeral of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II on Monday 19th September, 2022.

A timeline of the reign of Queen Elizabeth II

After the death of Her Majesty, we look back at key moments from her 96 glorious years.

Queen Elizabeth II: Tributes from around the world to Britain's longest-serving monarch

The Queen's Corgis: All about Her Majesty's most loyal subjects

As we mourn the passing of Queen Elizabeth II, we take a look at her corgis, the dogs that were

The Queen's official portraits: Seven of the most extraordinary paintings from 70 years and over 1,000 sittings

Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II has been painted literally thousands of times since she came to the throne. Charlotte Mullins

Curious Questions: What is a jubilee?

The celebration of HM's Queen Elizabeth II Platinum Jubilee is imminent — but what is a jubilee, and where does this