'He was really the most radical artist of the 19th century': Georges Seurat at the Courtauld Gallery

Georges Seurat spent much of his short life painting the quietude of the Northern French coast, honing his rigorous technique on the play of light, sky and water.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The sea called to Georges Seurat. Every summer, he fled to Normandy, ‘to wash his eyes of the days spent at the studio,’ as he told the Belgian poet Émile Verhaeren, and ‘translate as accurately as possible the bright light, in all its nuances’.

Although today he is most readily associated with Paris and the suburbs he captured in his seven ambitious paintings, including Bathers at Asnières and A Sunday on La Grande Jatte, ‘for Seurat’s contemporaries, his avant-garde friends, it was actually his sea-scapes that were most characteristic and most important,’ says the head of the Courtauld Gallery, Ernst Vegelin van Claer-bergen. ‘They represented that extraordinary sense of stillness, of quietude, that is so distinctive of Seurat and they were an absolute cornerstone of his life and of his art.’

So much so that the Courtauld, which has the UK’s largest collection of the artist’s work, is now devoting an entire exhibition to ‘Seurat and the Sea’, presenting some 17 paintings, plus oil sketches and elaborate drawings, many of which have never been seen in this country before.

Seurat, says the gallery’s senior curator of paintings, Karen Serres, is a little like Vermeer and Pieter Bruegel the Elder, in that there are only a little more than 40 known, finished paintings by him, 38 of which he exhibited in his lifetime. Those were the ones that made his reputation and the vast majority of them, 24, are marine views.

Indeed, even critics who panned his larger canvases appreciated his coastal works: the same man who could not ‘abide his Sunday at La Grande Jatte, which is crude in tone and in which the figures are cut out like poorly made mannequins’ praised the ‘extreme delicacy of colours in his suite, particularly of the seascapes of Grandcamp’. However, adds Dr Serres, his sea and Parisian pictures should not be seen in opposition: the ones influenced the others throughout his short life.

'He completely transformed the Impressionist style into a very specific technique, Pointillism, having dots of pure colour side by side to render light'

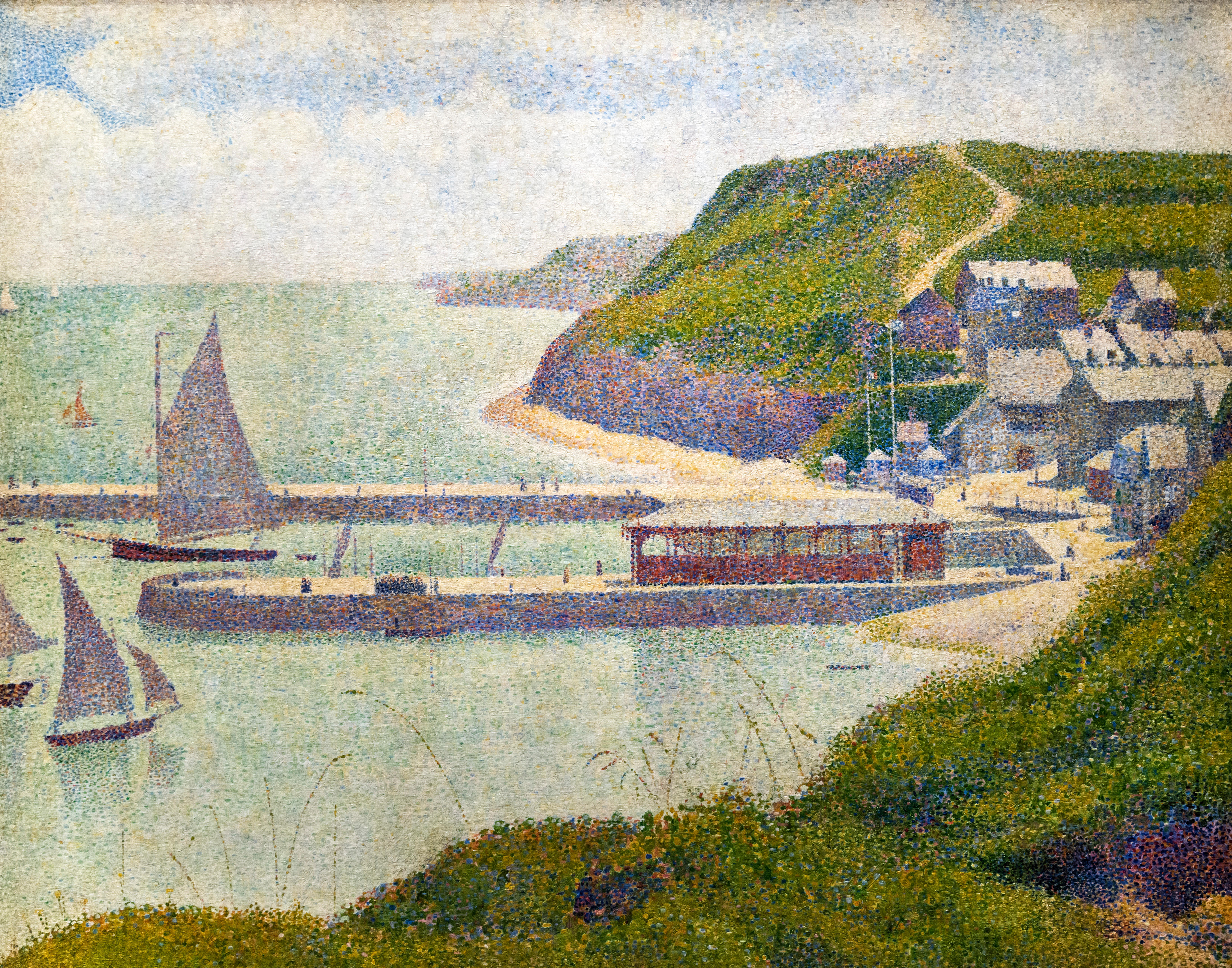

Port-en-Bessin, avant-port, marée haute (1888)

Seurat was born in the French capital in 1859 and trained first at the École Municipale de Sculpture et de Dessin, then, from 1878, the École des Beaux-Arts, although, a year in, he left for military service. When he returned, having explored the coast of France from his posting in Brest, Brittany, he decided to forgo the school to set up on his own.

‘He had a very traditional education, but he rapidly forged his own path, looking to the Impressionists, their use of colour, and also, crucially, [their] subjects of modern life, but creating his own idiom,’ explains Dr Serres. His family was affluent enough to support him, which allowed him to pursue his artistic interests freely. ‘He was really the most radical artist of the 19th century,’ Dr Serres believes. ‘He completely transformed the Impressionist style into a very specific technique, Pointillism, having dots of pure colour side by side to render light.’

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

His method was grounded in scientific rigour. Painters had long intuitively understood that the same hue, when placed next to black, white or grey, takes on different values or that, if it’s placed next to a complementary colour, both appear more vivid. Seurat, however, turned to new developments in optical theory, deliberately juxtaposing pigments at first in short strokes, then in dots, so that ‘they would fuse in the eye of the beholder,’ says Dr Serres.

Even the palette where he mixed his paints reflected his approach. Whereas Monet’s was encrusted with a messy explosion of vibrant blobs — proof perhaps of the instinct and spontaneity that artist Paul Signac said drove the Impressionists — Seurat’s was painstakingly organised. At the bottom he had black pigments, at the top he had white and in the middle row, progressing neatly from left to right, a sequence of hues from the palest yellow to the darkest blue.

'It’s very interesting to see how he’s starting to become more and more abstract in many ways. Had his life not been cut short, we don’t know how his art would have evolved'

If science was his basis, however, the sea was his catalyst. It was the place where this reserved, introspective artist could reflect and explore light in large spaces empty of people — so much so that he demurred when his friend Signac suggested joining him. ‘The relationship between sky and water and light was absolutely crucial for him to develop his technique, which is why every time he came back to Paris after spend-ing the summer on the coast, he said it refined what he was trying to do,’ notes Dr Serres.

The evolution of his method is evident in the seascapes on display at the Courtauld. In his early pictures, he may have added a few strokes of red next to pink and blue, but, by 1888, says Dr Serres, ‘you can see the incredible mixture of colour to render the light falling and the shadows on the coast’. His dots have become smaller, the range of their colours greater. ‘In 1890, two years later, his method became much more separated, much more pure.’

The north of France was his summer destination. With the exception of 1887, when he remained in Paris, probably to finish his grand winter works Models and Circus Sideshow, he went there every year from 1885 to 1890. Armed with a boîte à pouce, or à pochade — a compact box complete with mini-easel, which took its name from the fact that it had an opening for the thumb that allowed it to rest on the artist’s hand — he would sit on the beach and sketch on wooden panels. ‘We found embedded in the paint a lot of sand,’ says Dr Serres. ‘He really was working out of doors, very much following the Impressionist tradition.’

No sand was ever retrieved in his exhibition paintings, however, suggesting they were made indoors and probably finished in Paris. Critics saw a touch of sadness and melancholy in his sea-scapes, but Seurat disagreed. His friend and fellow artist Charles Angrand recalled him saying: ‘They see poetry in what I do. No, I apply my method and that is it.’

The Channel of Gravelines, Petit Fort Philippe

Much as his technique progressed over the years, so did his choice of seascapes change. Initially, explains Dr Serres, he painted the coastline of Normandy that had caught the eye of Eugène Boudin and the Impressionists before him: small fishing villages such as Grandcamp and resorts frequented by middle-class Parisians on holiday, including Honfleur. In time, however, he became more interested in less popular places, such as the canal at Gravelines, a town near Dunkirk.

There, in the most productive of his summer ‘campaigns’, he used a tighter spacing of dots and a more restricted palette to render the open skies that most seemed to interest him at the time. ‘It’s very interesting to see how he’s starting to become more and more abstract in many ways,’ says Dr Serres. ‘Had his life not been cut short, we don’t know how his art would have evolved.’

Seurat’s four Gravelines paintings were on show at the newly opened 7th Salon des Indépendants when he died suddenly on March 29, 1891, aged only 31, probably of diphtheria, although Signac thought he had ‘killed himself by overwork’.

Such was the late painter’s affinity for the Northern French coastline that Angrand, when visiting Dieppe after Seurat’s death, wrote to another common friend, ‘I thought of him as I always do when looking out to the sea. He is the first to have rendered the feeling it inspires on quiet days… The truth was that the tone of his palette, a unique tone, captured the essence of things.’

'Seurat and the Sea' is at the Courtauld Gallery, London, from February 13–May 17

Carla must be the only Italian that finds the English weather more congenial than her native country’s sunshine. An antique herself, she became Country Life’s Arts & Antiques editor in 2023 having previously covered, as a freelance journalist, heritage, conservation, history and property stories, for which she won a couple of awards. Her musical taste has never evolved past Puccini and she spends most of her time immersed in any century before the 20th.