'A bluff, honest man in the trappings of greatness': The extraordinary story of the Foundling Hospital, and the sailor who saved the abandoned children of London

A remarkable charitable endeavour to save abandoned children on the streets of London has a touching legacy in the form of the The Foundling Museum in the very centre of London. John Goodall tells its story; photographs by Will Pryce.

In about 1722, a retired sea captain called Thomas Coram was so distressed by the number of unwanted babies he witnessed abandoned, murdered or mutilated on the streets of London that he began to promote the idea of an institution that could look after these so-called foundlings. The treatment of such children was then a matter of current concern, famously discussed, for example, in Jonathan Swift’s excoriating satire A Modest Proposal for preventing the Children of Poor People from being a Burthen to their Parents or Country and for making them beneficial to the Publick, composed in 1728–29, and a theme of Henry Fielding’s comic novel The History of Tom Jones, A Foundling, published in 1749.

Poverty was the main driving force behind abandonment, but the stigma of having children outside wedlock played a part as well. Great cities in Catholic Europe had charitable bodies to deal with the problem, such as L’Hôpital des Enfants-Trouvés in Paris, France, founded in 1640. In Ireland, Dublin had established a foundling hospital attached to its Poor House in 1729, although three-quarters of the children received there died in the first seven years of its operation. By contrast, London — increasingly conscious of its status as the capital of the wealthiest nation in the world — had nothing.

Fig 2: William Hogarth’s 1740 portrait of Capt Thomas Coram at his moment of triumph. He holds the royal seal of the hospital charter, issued on October 17, 1739, in one hand.

Coram had been sent to sea at the age of 11 without formal education and was ruggedly mannered. He undertook several philanthropic initiatives during his lifetime, however, and determinedly set to work seeking the signatures of members of the nobility to a petition setting out the problem addressed to the King. Recalling their hostility many years later, he said they reacted as if he had asked them to ‘put down their breeches and present their backsides to the King and Queen in a full drawing room’.

On March 9, 1729, however, Coram had a breakthrough when Charlotte, Duchess of Somerset, signed his petition. She was the first of 21 ‘leaders of quality and distinction’, all women at Court, who backed his plan. This ‘ladies’ petition’, presented in 1735, did not succeed and a ‘gentlemen’s petition’ was required two years later to secure meaningful progress. It was signed by 375 wealthy and influential individuals, including 25 dukes, 31 earls, 26 other members of the peerage, 38 knights, 66 merchants and 72 MPs.

Fig 3: The façade of the 1936 house on the north side of what is today Brunswick Square, WC1. It is now the home of the Foundling Museum. Coram’s bust appears over the door.

A royal charter of incorporation for what was called the Hospital for the Maintenance and Education of Exposed and Deserted Young Children was issued on October 17, 1739. Its preamble explains that the petitioners, ‘sensible of the frequent murders committed on poor miserable infants by their parents, to hide their shame, and the inhuman custom of exposing new-born children to perish in the streets, or training them up in idleness, beggary, and theft’, had declared ‘their intentions to contribute liberally towards the erecting an Hospital… for the reception, maintenance, and proper education of such helpless Infants’.

At Coram’s instigation — and reflecting his business experience — the charitable structure of what became familiarly known as the Foundling Hospital was effectively constituted in novel form as a joint-stock company, with its governors acting as shareholders. One incentive for generosity towards the venture, moreover, was that it enjoyed fashionable notice. A month after its issue, the Royal Charter was read out by Coram, now aged 70, at a special ceremony in Somerset House, the palace of England’s queens.

One of those present was the artist William Hogarth, who had already painted the stair of St Bartholomew’s Hospital, EC1, another great charitable initiative of the moment. In 1740, he produced a portrait of Coram at his moment of triumph (Fig 2). In it, the benefactor is presented as a sailor, red-cheeked and with a mop of real white hair, rather than a wig. The implicit message is of a bluff, honest man in the trappings of greatness. Such transpositions of status were a theme of the moment and are central, for example, to The Beggar’s Opera by John Gay (1728).

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

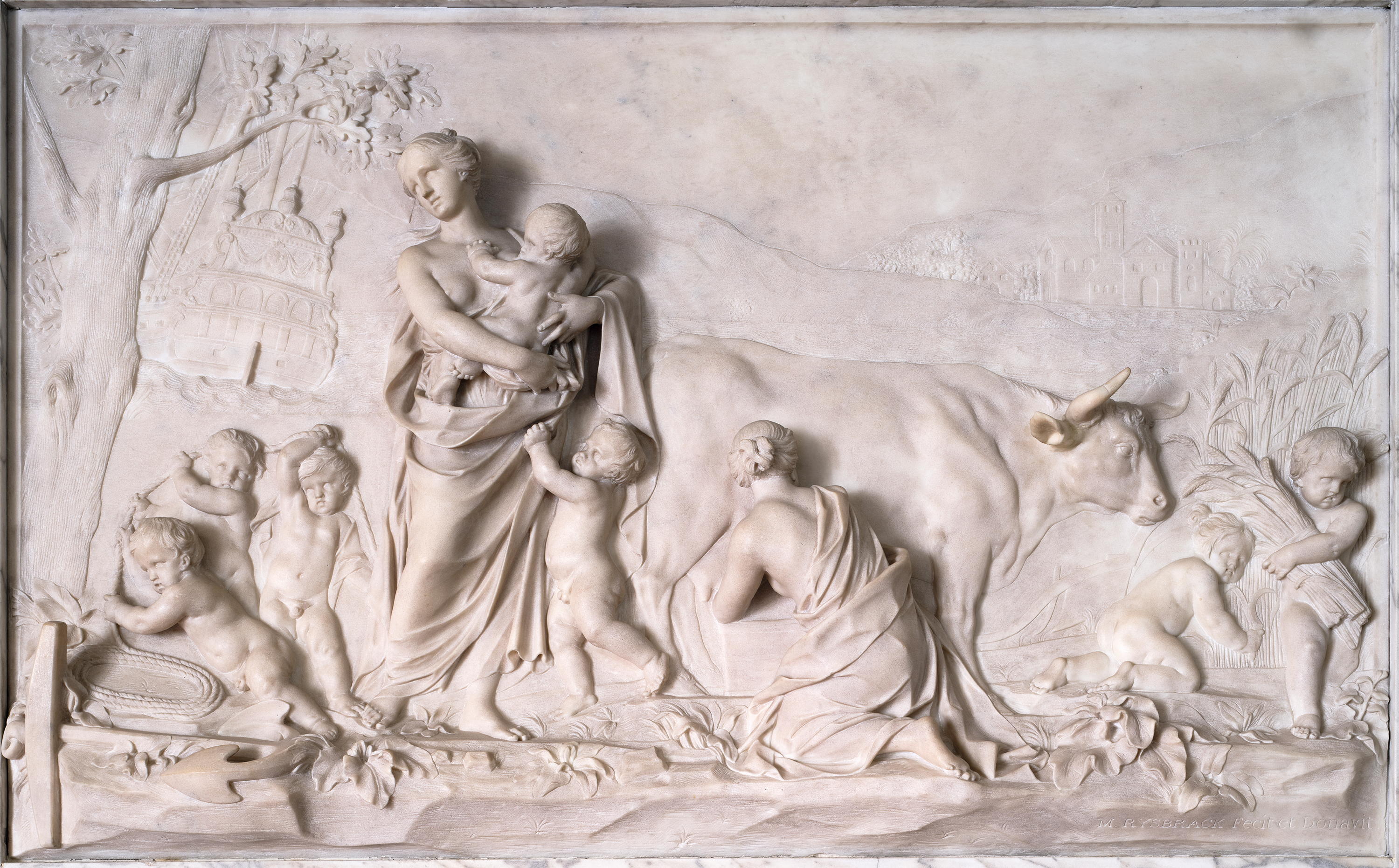

Fig 4: John Michael Rysbrack’s fireplace overmantel in the Court Room depicts young children with a figure of Charity. The anchor and ship hint at future naval service.

The first reception of infants took place at 8pm on March 25, 1741, in the temporary home of the institution, a house at Hatton Garden, EC1. A printed advertisement promised places for 20 babies under the age of two months and directed that, as each infant was being inspected for evidence of contagious disease, the individual who brought them was to wait in the lobby. They were also required to attach to the child some ‘writing, or other distinguishing mark or token, so that the children may be known hereafter if necessary’.

We know from later receptions of infants at the hospital that such tokens (Fig 5) could take the form of a coin or a trinket. Most commonly, however, they were swatches of fabric taken from clothes. When a child was received, it was given a number and its possessions described on a printed sheet. This was sealed up with the token, effectively rendering their original identity a closed secret. The mother’s name was not recorded and, in the event of someone returning to claim their foundling, the token then served as proof of the identity of both parties.

Fig 5: Every foundling was left with a token, perhaps a trinket, penny or ring, each one a memento of a severed connection between a mother and her child. Of 16,282 infants received in 1741–60, only 152 were reclaimed. Most tokens were swatches of clothing, so the museum possesses one of the largest collections of everyday fabrics to survive from Georgian Britain.

The advertisement for the first reception assured readers that ‘no questions whatever will be asked of any person who brings a child’; the unusual timing after dark was probably further intended to ensure anonymity. According to the General Evening Post the following day, ‘19 males and 11 females, being all that could be received’ were taken into care. Its report further announced the forthcoming baptism of the children ‘with some of the first rank of nobility… to stand godfathers and godmothers’. The first boy, it stated, would ‘be named Thomas Coram, after the name of the first promoter of the said establishment’ and the first girl after his deceased wife, Eunice (she had been born in Boston, Massachusetts, US, and their marriage was childless). It was intended that the ‘robust boys’ would eventually be sent to sea and several were, therefore, named after ‘our great men of former times as Drake, Norris, Blake and other fam’d admirals’.

Newly christened, the tiny infants were dispatched to nurses, who assumed responsibility for fostering them, and the governors set to work creating a permanent home for the hospital on a greenfield site to the north-west of the city. Coram was involved in identifying the plot, but, in the spring of 1742, the other governors tired of him and he was eventually ejected from what he called ‘my darling project’ in uncertain and painful circumstances.

Even without Coram, the unusual structure of the charity now drove it forward. A Steelyard merchant of German family (and a founding governor), Theodore Jacobsen, volunteered a design for the hospital. He was an architectural amateur who had previously provided plans for East India House in the City in 1726 and, for the Foundling Hospital, he proposed two facing ranges, one for boys and one for girls, linked by a central chapel.

The inner faces of this three-sided courtyard were opened out at ground level to create vaulted walks. A foundation stone was laid in September 1742 and construction began under the direction of a professional joiner, James Horne, who gave his services as surveyor free of charge. Jacobsen henceforth enjoyed a reputation as a designer of institutional buildings and, in 1745, presented plans for the Royal Hospital at Haslar, Gosport, Hampshire, a project also supervised by Horne. He provided plans for the main quadrangle of Trinity College Dublin, Ireland, too.

The austerely detailed hospital (Fig 8) took shape slowly as funds came to hand with the first range, constructed cheaply from brick, opening in 1745. Following Hogarth’s lead, other artists — such as Thomas Hudson, Allan Ramsay and John Michael Rysbrack (Fig 4) — gave and displayed works of art in the hospital, using it as London’s first public art gallery. The initiative foreshadowed the foundation of the Royal Academy in 1768.

Fig 7: A view of the Hospital before its controversial demolition in 1928. The whole site sold for a sensational £1.65 million in 1924.

In May 1749, composer George Frideric Handel performed a benefit concert for the Foundling Hospital in the incomplete chapel (Fig 6). He returned a year later to perform Messiah, which had enjoyed its premiere in Dublin in 1742. Such was its success that the oratorio was performed annually into the 1770s, a run of concerts that established its popular reputation in the British choral repertoire. Handel also gave the chapel its organ.

In its first 15 years, the hospital received 1,384 infants. Demand for places, however, massively outstripped availability. Admission had to be balloted using black and white balls (with red balls offering the possibility of a place if a successful child was unexpectedly rejected). Disappointment was the rule. Between 1749 and 1756, only 803 of the 2,808 babies brought were accepted. Boys were entered into apprenticeships from the age of 10 and girls went into domestic service.

In 1756, however, Parliament agreed to fund the hospital if it accepted every child delivered to it. The maximum age of admission was also raised to six months (and later a year). In response, there was a surge in admissions and, over the next four years, 14,934 infants were received. Whereas most babies had originally come from London, the catchment area expanded to the wider kingdom as parish officers saw the opportunity to relieve themselves of the financial burden of poor children.

To accommodate so many foundlings, new branches of the hospital were created as far afield as Chester, Shrewsbury and Ackworth, West Yorkshire. Mortality rates were shockingly high: about two-thirds died. Of the 16,282 infants received between 1741 and 1760, only 152 were reclaimed by their mothers.

Fig 8: The Hospital in a 1746 painting by Richard Wilson from the Court Room. Costruction was still in progress, hence, perhaps, this view, which conceals the chapel.

Parliament’s generosity faltered in 1760 and the hospital’s function began to change. From 1763, a system of admission by petition was adopted, in which mothers gave their name and a reason for their child’s need for a hospital place; most commonly poverty brought about by desertion, rape or ‘seduction’. From 1795, the emphasis shifted again and places were offered for the purpose of restoring single mothers ‘to work and a life of virtue’. In 1801, it was decided only to receive illegitimate children and orphans of servicemen.

David Beckham on the Foundling Museum

'I find this piece so moving as I’ve always been motivated to try to help children, from coaching them on the football field to working for UNICEF, an incredible charity that does so much for youngsters all around the world.

'I knew that being a Goodwill Ambassador would be rewarding, but I did not realise how helpful my football career would be. Even in the remotest parts of Africa where they don’t have televisions, they have radios; as I’ve played for teams such as Manchester United and Real Madrid, the children have heard of me and Ronaldo. It helps us form a bond and means I can shine a light on their plight.

'We might not speak the same language, but the love of the game brings us together when we’re kicking a football about on a muddy pitch in Sierra Leone.'

Over the 19th century, the Foundling Hospital (Fig 7) increasingly assumed the character of a school and its site was gradually engulfed by London. There was a strong music tradition and many boys joined military bands. After the First World War, the governors decided to follow the example of other educational institutions and move out of the city to a healthier rural setting. The children went first to temporary accommodation at Redhill, Surrey, in 1926 and then, in 1935, to a purpose-built school at Berkhamsted, Hertfordshire. In 1955, however, the decision was made to close the school and place all the children in foster care. Today, the foundation, known as Coram, comprises a group of specialist charities helping more than a million children, young people, professionals and families every year.

The Foundling Hospital itself, meanwhile, was left empty and, in 1928, despite strong opposition and alternative suggestions of use (including as a university building), it was demolished. A local group supported by Lord Rothermere bought the site to save it from development and created what is now known as Coram’s Fields, where adults can only go in the company of a child. Part of the Foundling Hospital gate and two Doric colonnades are all that survive in situ of the original buildings.

In 1936, the governors bought back a strip of the land on which architect J. M. Shepherd created an unassuming Georgian house facing onto what is now Brunswick Square as the headquarters of the charity (Fig 3). It incorporates several remnants of the old building including, most importantly, the reconstructed Court Room of the 1740s (Fig 1). Since 2004, this has served as the home of the Foundling Museum, which tells the poignant story of this institution and also displays its outstanding art collection to the public.

The exhibition ‘A Grand Chorus: The Power of Music’ is at the Foundling Museum, No 40, Brunswick Square, London WC1, until March 29, 2026,

This feature originally appeared in the October 22, 2025 issue of Country Life. Click here for more information on how to subscribe.

John spent his childhood in Kenya, Germany, India and Yorkshire before joining Country Life in 2007, via the University of Durham. Known for his irrepressible love of castles and the Frozen soundtrack, and a laugh that lights up the lives of those around him, John also moonlights as a walking encyclopedia and is the author of several books.