Portmeirion: A century of peculiar genius at Clough Williams-Ellis's great village experiment

2026 marks the centenary of Portmeirion, one of the most celebrated holiday villages in the British Isles. Kathryn Ferry tells the remarkable story of this Picturesque creation; photographs by John Goodall.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In April 1927, a small advertisement for Portmeirion appeared in the pages of Country Life. Competing against notices for far grander, more luxurious hotel accommodation, the offer of ‘Furnished Cottages in old garden at the sea’s edge, on private promontory between Harlech and Criccieth’ stood out by virtue of its accompanying photograph.

Behind the central trunk of a mature tree, wisps of white smoke rose from the chimneys of The Angel and The Neptune, the quaint semi-detached pair of new cottages with which Clough Williams-Ellis began his model village experiment. The gentle curve of the jettied Angel with its roof of local slate was in the Arts-and-Crafts tradition, but the contrast it presented with the elaborately barge-boarded and newly converted early-Victorian gardeners bothy, at the edge of the photograph, hinted that this was not to be a typical seaside development.

Socially well connected and professionally successful, the Welsh architect known as Clough was a prolific writer and lobbyist on behalf of the emerging ‘amenity’ cause, what we would now call environmental and heritage protection. Clough’s voice would be loud in the Council for the Preservation of Rural England (CPRE) and its sister organisation in Wales, the Georgian Group and the National Parks campaign, among many others.

He is best remembered, however, for the holiday resort that opened 100 years ago this year, as a three-dimensional manifesto intended to put his preaching into practice. What he achieved at Portmeirion is so delightful that visitors barely feel the propaganda seeping into their souls, yet it is relevant still. The fundamental pleasure Clough took from architecture and his desire to awaken that in others remains profoundly uplifting.

Fig 2: A view through the Gatehouse, 1954–55, with its mural by Hans Feibusch.

Portmeirion was conceived in a period before planning legislation, when beauty spots seemed assailed by encroaching urban sprawl and ‘bungaloid growth’ ribboned along roads at a pace commensurate with the rise in car ownership. In his early forties and having come through the First World War, Clough wanted to prove that building a settlement from scratch did not have to mean spoiling the essential qualities of a landscape. He was angry about the waste and wanton destruction of war, all the more so because the countryside veterans that had been led to believe they were fighting for continued to be under threat. Given his urgent calls for reform and his friendships with the era’s leading town planners it is perhaps surprising that Portmeirion never had its own masterplan, nor were there many conventional architectural drawings of its buildings and subsidiary structures.

Clough often recalled how the dream of creating his own village came upon him as a boy of only six or seven, with ideas flowing from that point onwards. When, after fruitless searching for an island location, he found the perfect site not five miles from his own family estate and available to buy from his uncle, Clough responded first to the realities of the place and then to the exigencies of his pocket. In the enviable position of being owner, architect and developer, he also carried the financial risk, which led to an inherent thriftiness in his aesthetic choices. This proved to be no hardship for someone with Clough’s magpie tendencies and deft imagination, arguably generating a far more organic and satisfying result than if money had been no object.

Fig 3: A view of the Dwyryd estuary. Changes in the weather can transport the viewer from Wales to southern Europe and back again.

Construction occurred in two phases, from purchase of the site in 1925 until the outbreak of war in 1939, then, after a long hiatus and with Clough having left London to live back in Wales, from 1954 until completion in the mid 1970s. As Clough himself conceded, the buildings of Portmeirion were thus a ‘pretty mixed lot… a reflection of my own preferences or impulsions at the period’. The different styles, shapes and colours were united by his own unique treatment with an underlying consistency afforded by a kindred relationship between himself and the local Davies family of master masons, father and sons, who interpreted his vision over 50 years.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The Aber Iâ estate had long been neglected by its reclusive tenant, so the task of transforming it into Portmeirion was begun by reclaiming from the wilderness the century-old lawns and rockeries, wooded walks and grottoes. In awakening his very own Sleeping Beauty, Clough revealed the exotic flora and fauna that would become the backdrop to his new pleasure grounds. At the water’s edge, a Gothick marine villa of the 1840s was prettily situated above the quay, its private seafront tamed by a balustraded terrace. Repaired and tidied up, this was to become the nucleus of the hotel, the essential income generator that would prove ‘good architectural manners were also good business’ (Fig 4).

Fig 4: The hotel was created out of a pre-existing villa. The teal of the gate, windows and shutters is used throughout the village.

Writing in The Hotel Review in 1934, Clough explained his ongoing building programme of separate holiday houses linked to it, reasoning that families and parties liked their own space and, if his venture failed and the hotel trade dried up, his little seaside cottages would still have value. With keen self-awareness, he confessed: ‘I suspect that the real reason may be that it is better fun building a sort of small town than sticking more lumps on to an old building that was knobbly enough already.’ For all that the underlying message was serious, Portmeirion’s charm has always been its playfulness, a notable quality of seaside archi-tecture that Clough instinctively harnessed to provide a holiday escape for his guests and a continuing source of enjoyment for himself.

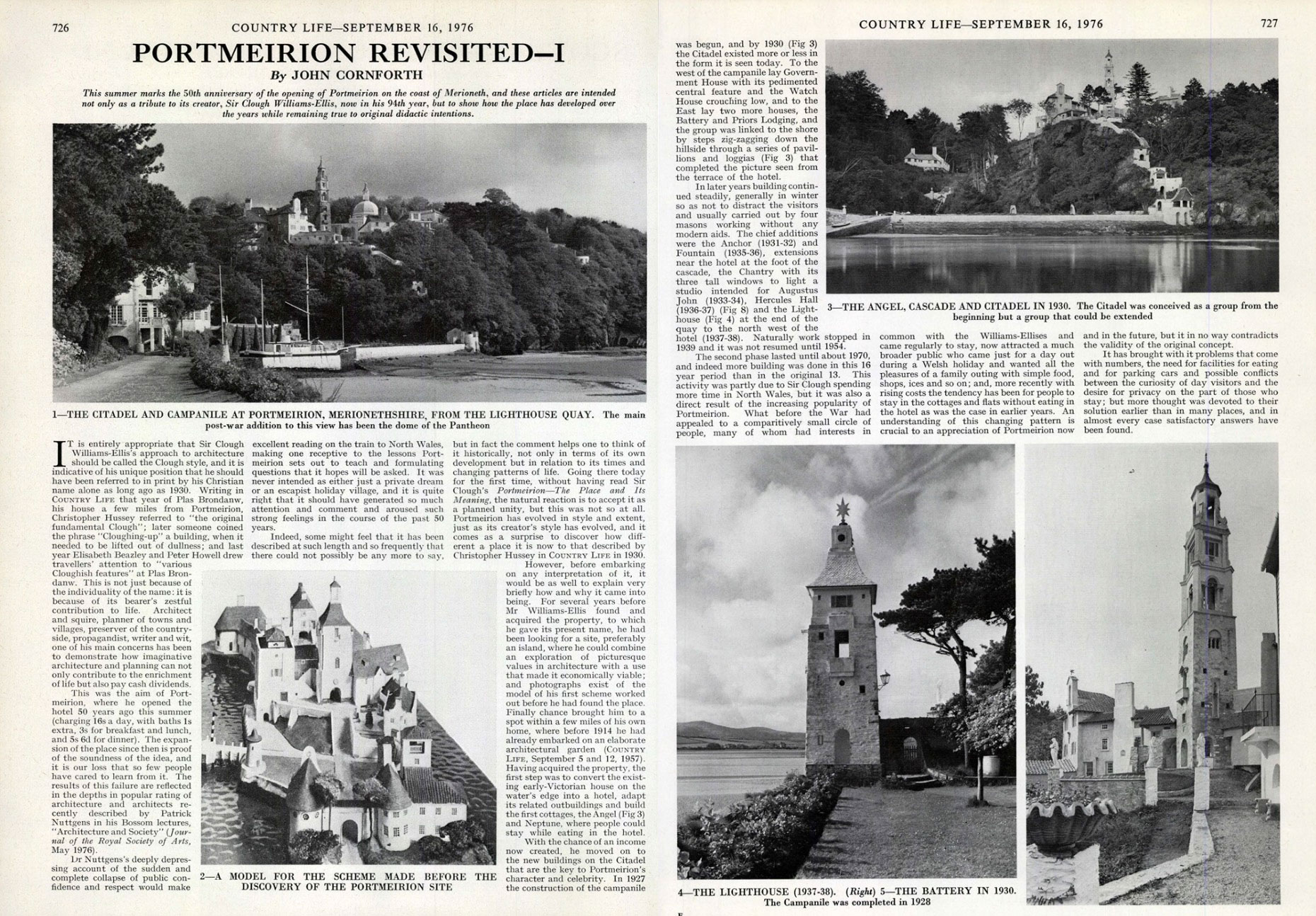

In the late 1920s, his fun was at its most Italian-looking. Having identified the key sites, he began construction of clifftop focal points around which later buildings would coalesce. Inspired by Italian travels, Clough sought to reproduce the ‘friendly intimacy of so many old coastal towns and villages, particularly in the South and particularly Portofino’. The Watch House and Battery were part of the original cluster around the Baroque Campanile, a functionally useless structure that was nonetheless crucial in terminating views and creating the right Mediterranean flavour. Roofs were tiled with warm terracotta, notwithstanding family interests in the nearby Blaenau-Ffestiniog slate quarries, and a walk was created down the cliffside, punctuated by loggias (Fig 3) and pavilions to enhance the feeling of height and visually tying the lower quay to the citadel above (Fig 1).

Colour was established as another key ingredient, influenced not only by Italy, but also the work of friend and artist Claud Lovat Fraser, whose set designs for the 1920 production of The Beggar’s Opera informed Clough’s ‘light opera’ approach. As John Cornforth noted in Country Life on Portmeirion’s 50th anniversary, the contemporary context was ripe with coincidence, the romantically layered murals by Rex Whistler for Tate and Plas Newydd, for example, and the publication in 1924 of Sacheverell Sitwell’s Southern Baroque Art, as well as Christopher Hussey’s seminal 1927 history The Picturesque.

Portmeirion as featured in Country Life in 1976.

In some ways, then, Portmeirion can be understood as peculiarly ‘of’ its time, yet the greater part of building happened after the Second World War when sources became more varied. Wartime shabbiness had to be corrected, but demand from hotel visitors stayed strong and the day-trip audience continued to grow. Clough understood holidaymakers’ desire for novelty, so each winter saw a campaign of works; for every utilitarian require-ment satisfied, he allowed himself a flowering of fancy, a gateway, statue, belvedere or fountain. Battery Square was enclosed to make a cobbled piazza with swirled gables over its little shops and archways directing views and feet through. It was a beloved device of Clough’s to create frames, be they arches, porthole windows or short tunnels, as under the 1950s Gatehouse (Fig 2) and Bridge House.

Fig 5: The Bristol Colonnade, with Chantry Row and its theatrical half-onion dome above.

He enjoyed the sensation of walking beneath buildings that straddled the street, moving from a brief ‘feeling of cosy enclosure’ into the light that felt brighter for the contrast. It was one of many impressions he wanted his architecture to share. His underlying preference for Georgian Classicism came out more, too, although the end of Chantry Row butted on to a tower with an onion dome (Fig 5) as if to refute any possibility Clough might be getting too predictable. When asked what his new domed Pantheon was for, he replied that it was ‘built to fill a severe dome deficiency’ — and it did (Fig 6). The creation of new axes around the Green seemed to demand it. Certainly, it is hard to conceive of a more pleasing end to the vista looking up from the Town Hall. Of course, it is all an illusion; the elongated lantern atop the Dome, the salvaged Norman Shaw fireplace from Dawpool Hall in Cheshire that looks like a grand entrance, the little tiled loggia on a lower level that adds an extra sense of height. Up close, the Dome is found to be a sort of miniature.

Every such view — and there are countless examples — is carefully crafted. Trees, water and contours are all given skilled consideration in these seemingly casual ‘eye traps’. The genuine patina of reclaimed materials adds to the effect. Clough started his junk yard with truckloads of salvage from the Wembley Empire Exhibition and continued laying down pieces of architecture, ‘much as my grandfather laid down Port’. Some acquisitions enjoyed immediate reinvention, most notably the spectacular Jacobean ceiling from Emral Hall in Flintshire. In October 1936, the house was auctioned off in 350 lots. When no one else bid on the plasterwork Clough found himself taking it, and the rest of the room it came from, to become the core of a rapidly designed new Town Hall assembly room.

Fig 6: The Pantheon of 1960–61, built to satisfy a ‘dome deficiency’.

After the war, he was often tipped off about impending demolitions and revelled in Portmeirion’s growing reputation as a ‘Home for Fallen Buildings’. The Colonnade from Arno’s Court, Bristol, was once the front of a 1760s bath house damaged by German bombs. The best proposal council owners had for its reuse was as a public lavatory, so its removal to Portmeirion in the late 1950s was considered a far preferable option. The Dawpool fireplace, saved out of regard for its architect, had to wait some 30 years for Clough to envisage its reuse, but simply having such pieces available helped inspire his design process.

There is little obviously ‘modern’ architecture around the village. Clough welcomed the Festival of Britain in 1951, but could not come to terms with Brutalism. Only the curvilinear extensions to the main hotel, reinstated after a fire in 1981, speak to mid-20th-century trends and these, perhaps, were a nod to Oliver Hill’s Midland Hotel at Morecambe in Lancashire, widely praised in the early 1930s as a new concept in hotel design alongside Portmeirion. Hill and Clough were friends, described by Prof Charles Reilly in 1931 as the ‘two outstanding figures among the men of eminence in our profession’. Both created seaside developments, yet Hill’s Frinton Park, projected as a gleaming expanse of Cubist houses on the Essex coast, quickly failed. Clough, on the other hand, added slowly to the Welsh landscape he found and although his exotic vernacular shouldn’t work, it does.

Hussey, writing for Country Life in 1930, understood the pivotal role of Portmeirion’s creator: ‘Actually it is a personal expression of Mr Ellis’s peculiar genius.’ A century on, that genius is still very much in evidence.

Find our more at the Portmeirion website. With special thanks to Rachel Hunt and Sarah Baylis.