The magnificent London mansion that Country Life mourned when it was demolished to make room for the Dorchester Hotel

Dorchester House was once the epicentre of late-Victorian society.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The vast majority of lost mansions in the UK were demolished because of three reasons: war, fire or death duties that were imposed on estate-owning families throughout the 20th century. The latter is partly to blame for the demise of London’s Dorchester House — though Country Life dramatically decreed in a February 25, 1928, article that her fate had instead been sealed by 'the English Capitalists'.

Dorchester House was grand. Very grand — built on the site of another demolished building, on the capital's exclusive Park Lane, overlooking Hyde Park. Construction on the 40-bedroom behemoth began in 1849 for the exceptionally wealthy Capt Robert Stayner Holford (he'd inherited more than £1 million (about £97 million today) from an uncle), MP for East Gloucestershire, owner of Westonbirt House, founder of Westonbirt Arboretum and a voracious collector of fine art. Designed by architect Lewis Vulliamy and inspired by Rome’s Villa Farnesina, it featured an imposing porte-cochère with which to welcome visitors into the jaw-dropping marble entrance hall.

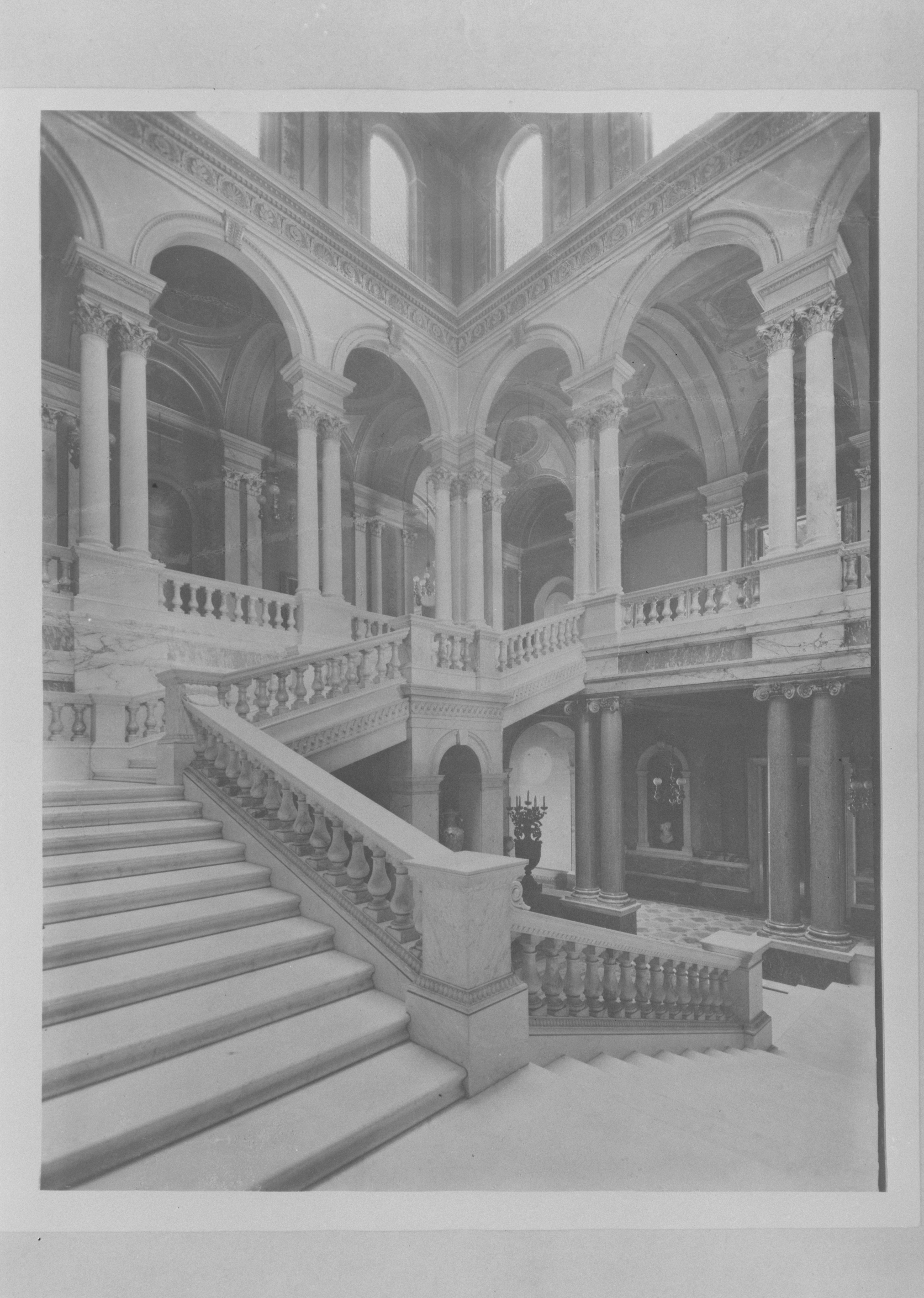

The imposing entrance to Dorchester House.

The hall and its grand staircase were said to have cost more than £30,000 (about £2.9 million) and featured Derbyshire alabaster balustrading. Each step was a different colour marble and the vast columns supporting the whole structure were carved out of pink granite

Holford and Vulliamy (who sought the advice of Sir Edwin Landseer while creating two arches in the saloon through which to view the marble masterpiece) contracted the finest artisans to work on the interior decoration. The library was hung with green damask silk and a huge, handwoven Axminster carpet laid on the floor. Sir Coutts Lindsay painted friezes in the Red Drawing Room and Signor Anglinatti decorated the ceilings in both this and the Green Drawing Room. No expense was spared — even when it came to one designer, Alfred Stevens, whose attention to the minutest of details pushed the generous Holford to his very limits.

Holford’s folly: The remarkable marble entrance hall and stair.

Stevens — whose quality and execution of work was, according to Country Life’s Christopher Hussey, on par with Michelangelo — took a staggering 10 years to complete a chimneypiece in the saloon. In May 1870, the usually Holford put pen to paper: ‘Had I known that the saloon chimney piece would have cost so large a sum as £1,800 [£187.500], I should, while admiring its beauty, have been content with good form and less ornament.'

The dining room chimneypiece by Alfred Stevens, with caryatid figures by his pupil, James Gamble. The whole item was salvaged and gifted to the British Museum by Robert McAlpine — the building contractors charged with demolishing Holford’s creation. It now resides in the Victoria & Albert Museum.

However, Holford did not terminate Stevens's contract and the work in the dining room continued until the latter died, mid-project, in 1875. When Holford discovered that Stevens had left a few small bequests to some poverty-stricken acquaintances, but no funds with which to honour them, Holford closed his account with a final payment of £100 (about £10,000 today) in the hope that they might receive something.

Dorchester House became, for a while, a hotspot for late-Victorian society. The balls thrown inside its walls were attended by royalty, including the then Princess of Wales (later Queen Alexandra).

Holford, who took great pleasure in showing off his impressive collection of art, died in 1892 and left the grand palace to his son, Sir George, an equerry to the royal household and, according the Manchester Evening News 'one of the best looking men in the kingdom'. Despite his handsomeness, Holford preferred the quiet life to grand state balls and parties, dedicating his spare time to collecting and tending to orchids.

He occasionally resided at the property, but, in 1905, rented it out to Whitelaw Reid, the American ambassador to London whose visitors included Edward VII and Queen Alexandra, Mark Twain and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. A press picture from 1910 shows former President Theodore Roosevelt (a regular visitor) departing the house the day the death of Edward VII was announced. The stars and stripes is at half-mast.

Sir Edwin Landseer’s suggestion in reality: The archway vista from the saloon to the entrance hall.

In 1912, Reid died and the house returned to Sir George. Two years later, he handed it over to the Government to use as a hospital for the duration of the First World War. Sir George was registered as living in the house in the 1921 census, but his tenure was not to last much longer. He died in 1926, leaving Dorchester House and Westonbirt to the Earl of Morley. Morley was already in a dire financial position having already inherited vast debts from both his father and grandfather and so he immediately put both properties up for sale. Dorchester House was only 70 years old, but already considered too old-fashioned to be worth salvaging — though there were 40 bedrooms, it had only five bathrooms. After a sale to a hotel syndicate was announced, Country Life mourned its imminent destruction:

‘A country that lives on capital, treating Death Duties as income, must not expect monuments of individualism to survive. Had the late Lord Leverhulme been alive and still contemplating he founding of a museum, as he was when he bought Grosvenor House, Dorchester House might have been spared. Had the Italian Government found it convenient to pay an extra £100,000, Italy would have had as worthy an embassy as England can offer, and London could have kept one of its noblest palaces. If Lady Beecham, in her gallant effort to house national opera, had also procured that last £100,000, the building would have been largely preserved.’

As was always the case, a huge pre-demolition sale was held. The vast staircase has depreciated in value quicker than a newly-released iPhone, selling in six individual pieces for a dismal £293. The Evening News reported that most bids were lower than the cost of removal. Solid oak doors, for example, fetched £3 3s (roughly £170).

The wrecking balls moved in as soon as the sale had finished and by 1931, The Dorchester Hotel had risen from its ashes. The luxury accommodation still stands proud in the footprint of Holford’s dream some 95 years later.

The Country Life Image Archive contains more than 150,000 images documenting British culture and heritage, from 1897 to the present day. An additional 50,000 assets from the historic archive are scheduled to be added this year — with completion expected in Summer 2025. To search and purchase images directly from the Image Archive, please register here.

Melanie is a freelance picture editor and writer, and the former Archive Manager at Country Life magazine. She has worked for national and international publications and publishers all her life, covering news, politics, sport, features and everything in between, making her a force to be reckoned with at pub quizzes. She lives and works in rural Ryedale, North Yorkshire, where she enjoys nothing better than tootling around God’s Own County on her bicycle, and possibly, maybe, visiting one or two of the area’s numerous fine cafes and hostelries en route.