The railway station gardens that bring a touch of bucolic bliss to an ordinary train ride

Gently tended by devoted staff, the railway station garden has become a rural idyll in its own right, says Andrew Martin.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In early writing about railways, trains tended to kill people or destroy Nature. In Dombey and Son by Charles Dickens, they do both. In his poem of 1844, On the Projected Kendal and Windermere Railway, Wordsworth asked: ‘Is then no nook of English ground secure/From rash assault?’

Yet it turned out that railways rather suited the countryside. They carried crops to market and did not sully the landscape unduly. By the start of the 20th century, they were often depicted as bucolic. In The Railway Children, the porter, Perks, gives the children strawberries from his garden. They talk to him as they recline on the ‘hot’ grass of a railway bank.

The country station was promoted as an idyll by the 100 or so railway companies of the time and many ran station-garden competitions. In 1900, The Railway Magazine noted that the North Eastern Railway (NER) gave out 200 guineas in prizes to green-fingered staff. A repeated winner was Castle Howard station in North Yorkshire (now closed). ‘What traveller going from Scarborough to York has not admired the lovely station of the château of the Howards?’ the magazine quipped.

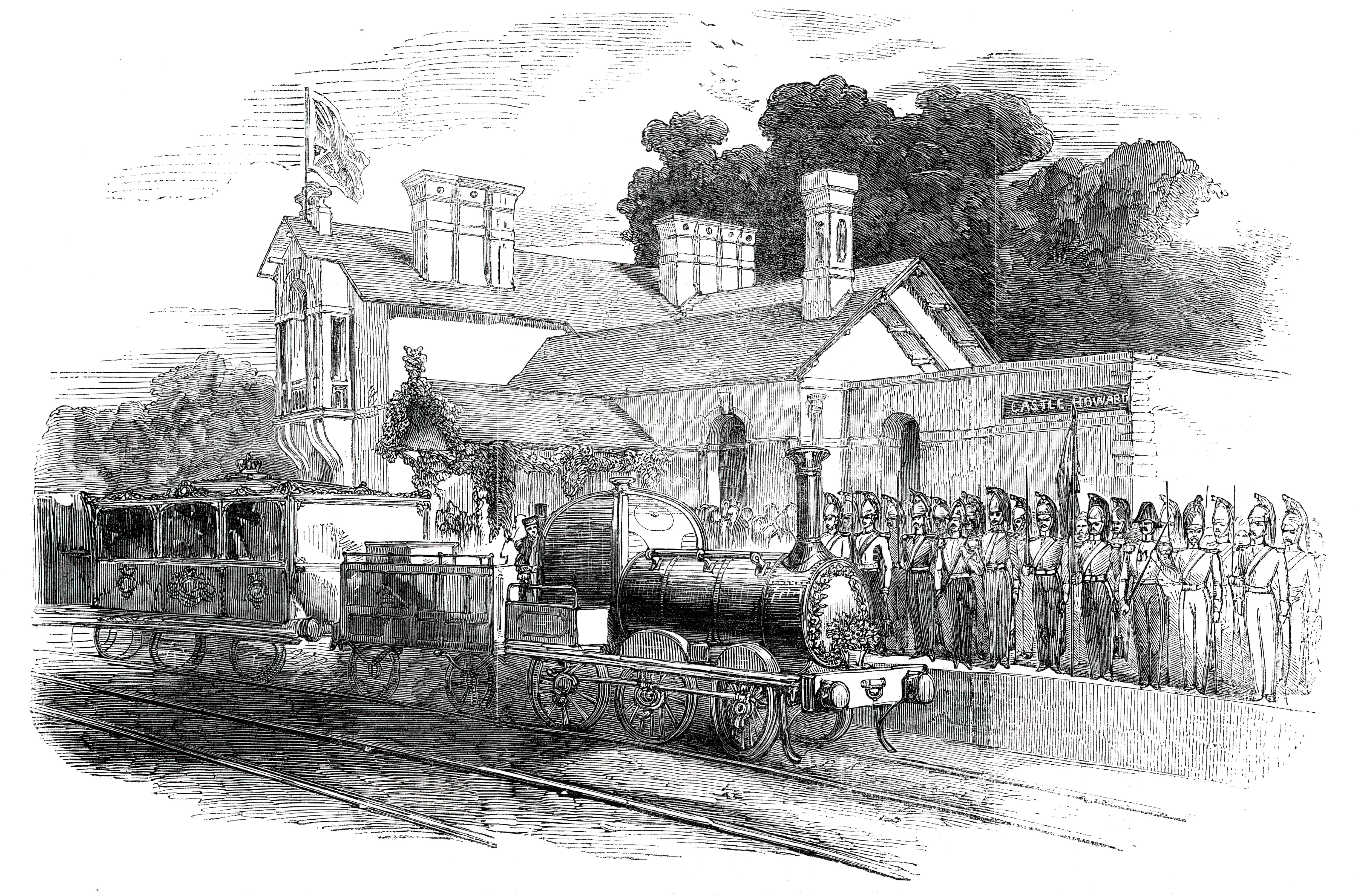

Queen Victoria arrives at Castle Howard Station in 1850 in an image printed in London Illustrated News, where people from across the country turned up to see Her Majesty. 'An awning, decorated with flowers and evergreens, was erected in communication with the station, through which the Royal party might pass, protected from the weather, to their carriages,' the paper reported.

Competitions continued into the interwar era of the ‘Big Four’ railway companies. Perhaps the high point came in 1930, when the London & North Eastern Railway (successor to the NER) fixed a bench to the front of a tank engine, to facilitate inspection by judges of station gardens in the north London suburbs.

The promotion of station gardens was part of the campaign among the Big Four to pitch railways as a more civilised method of transportation than automobiles. The car was a threat to the country stations especially and most of the lines closed by Dr Beeching in the 1960s were country branches. Staff cuts flowed from the closures. In 1948, there were 50,000 railway porters; today, there are none. Many of those porters were station gardeners and, as they departed, the weeds encroached.

Many station gardens disappeared with the stations that once hosted them. Thankfully, some still survive on heritage lines, such as North Dorset Railway Trust's Shillingstone Railway Station.

In 1993, Prof Paul Salveson (a former train guard) wrote a report called New Futures for Rural Rail, in which he envisaged volunteers assisting with station upkeep and coined the phrase ‘community rail’. Today, most of the surviving country branches benefit from the involvement of Community Rail volunteers, whose input is mainly evident in station gardens.

Prof Salveson commended the gardens at Pitlochry and Dumfries in Scotland and those along the Settle-Carlisle line. Among my own Community Rail favourites are those on Cornish branch lines, where sun-loving flowers such as petunias and zinnias, combined with palm trees, justify the old Great Western Railway’s audacious coinage, ‘the Cornish Riviera’.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Highland spring: the flowers bloom at Pitlochry Station in Perthshire

The gardens along the branch between Norwich, Norfolk, and Lowestoft, East Suffolk, are also impressive. The last time I visited Cantley station, for instance, an old rowing boat had been used as a planter, in which a pyracantha mimicked a mast (the sudden intimacy of the gardens on this stretch contrasts dramatically with the wide East Anglia horizon rolling by in between stations).

There are still many station-garden competitions. Perhaps the best known is Transport for London’s In Bloom, which has its origins in a competition started by the District Railway in 1910. The scheme is run by Ann Gavaghan, who says the aim is to ‘create moments of delight and surprise’, whether for passengers (observing, say, the sumptuous annual displays at Morden or West Kensington) or for staff — because not all the gardens are visible to the public.

Among past winners is a garden created on the roof of Goodge Street station, initiated by a staff member carrying a suitcase of compost up to the roof. Marigolds, nasturtiums and wisteria ensued. Invisible to the public, yes, but benefiting all by their absorption of CO2 generated by traffic.

Margate Station, Kent, encourages insect stopovers.

Railway stations and gardens go together because they are environmentally friendly. After all, the term ‘motorway service station garden’ does not readily trip off the tongue.

Andrew Martin is the author of the essay ‘Station Gardens’ in ‘The Untold Railway Stories’, edited by Monisha Rajesh (Duckworth, £22). His latest book, ‘To The Sea By Train’, is out now (Profile, £18.99)

Arley railway station, Worcestershire.

Andrew Martin is a novelist, railway historian and journalist. He is the author of the whose many books include the ‘Jim Stringer’ series of historical railway thrillers, as well as the author of several non-fiction books about the history of railways.