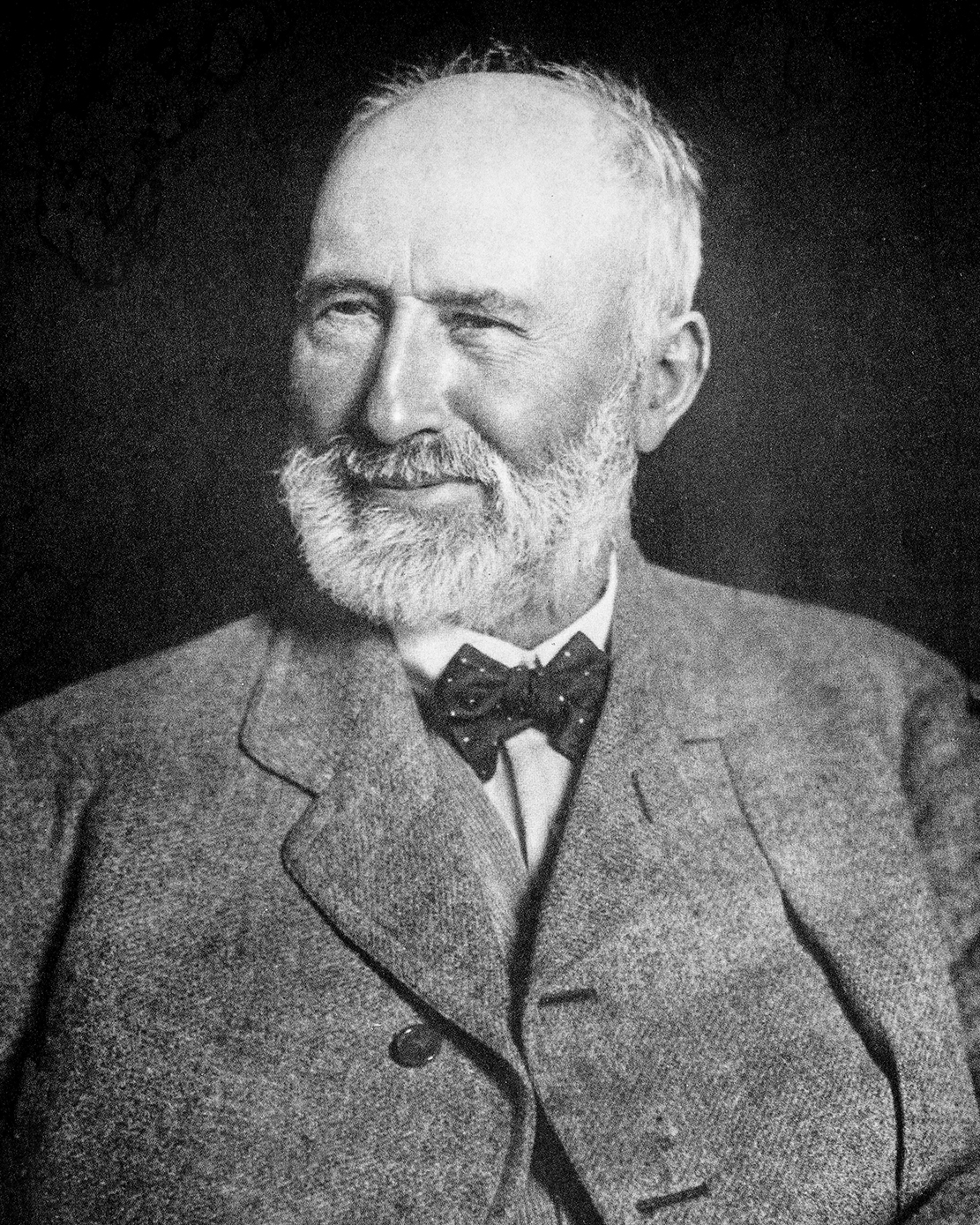

William Robinson, the visionary gardener 150 years ahead of his time

A century and a half before the word 'rewilding' entered the gardening lexicon, a pioneering gardener named William Robinson was advocating for a more natural approach to our green spaces. Tiffany Daneff examines his legacy, and his home at Gravetye Manor.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Long before anyone dreamt up the slogan No Mow May, the Irish-born Victorian gardener, writer and publisher William Robinson was urging gardeners to let the grass grow. In The Wild Garden Or Our Groves and Gardens made Beautiful by the Naturalisation of the Hardy Exotic (1870), he declared that ‘mowing the grass once a fortnight in pleasure grounds, as now practised, is a great and costly mistake’. It was far better to mimic Nature and plant things where they would be happy and become naturalised: turkscap lilies along a woodland walk, wild roses up old trees, little alpines in rocky ruins, herbaceous peonies in long grass.

If this sounds thoroughly modern, that is because we have come full circle and are rediscovering what Robinson knew more than 150 years ago.

Victorian gardener and writer William Robinson (1838-1935) advocated planting that mimicked Nature.

He railed against much of what was orthodox: carpet bedding, flowers grown in straight lines, over-manicured beds, the annual autumn digging of shrubberies, which only disturbed roots and prevented little woodlanders taking hold. The plants he recommended read like a list of those of today — grasses, wildflowers, such as mullein, species daffodils, American prairie plants, including Monarda, even Japanese knotweed... he didn’t get everything right.

Robinson had an eye for publishing also, tapping into the growing enthusiasm for gardening among the middle classes with two magazines: The Garden, founded in 1871 (and acquired by Country Life publisher Edward Hudson in 1900), was followed by Gardening Illustrated.

At his home, Gravetye Manor, an Elizabethan house in West Sussex that he bought in 1884 ‘as a poor farm’ (Country Life, March 23, 1918), all his theories were put into practice. On the slopes and in the woodlands thrived thousands of narcissus; autumn crocus, camassias and scarlet windflowers grew in the grass; hepaticas and lily-of-the-valley spread themselves through the copses; fritillaries, leucojum, day lilies and water forget-me-not put down roots beside water.

On the slope above the manor, he built a magnificent elliptical walled kitchen garden and close by the house a flower garden of ‘Tea and China roses underplanted with pinks, carnations, forget-me-nots and perennial pansies’. This living legacy is now cared for by Tom Coward, head gardener at Gravetye Manor; and for those who wish to visit and pay homage, the good news is that Gravetye Manor is, these days, a hotel.

Visit the Gravetye website for more information.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

This feature originally appeared in the January 21, 2026 issue of Country Life. Click here for more information on how to subscribe.

Previously the Editor of GardenLife, Tiffany has also written and ghostwritten several books. She launched The Telegraph gardening section and was editor of IntoGardens magazine. She has chaired talks and in conversations with leading garden designers. She gardens in a wind-swept frost pocket in Northamptonshire and is learning not to mind — too much — about sharing her plot with the resident rabbits and moles.