Sophistication on wheels: The most elegant method of train travel is still the sleeper

The appeal of being lulled to sleep as a sleeper train rattles homewards is synonymous with adventure and romance.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

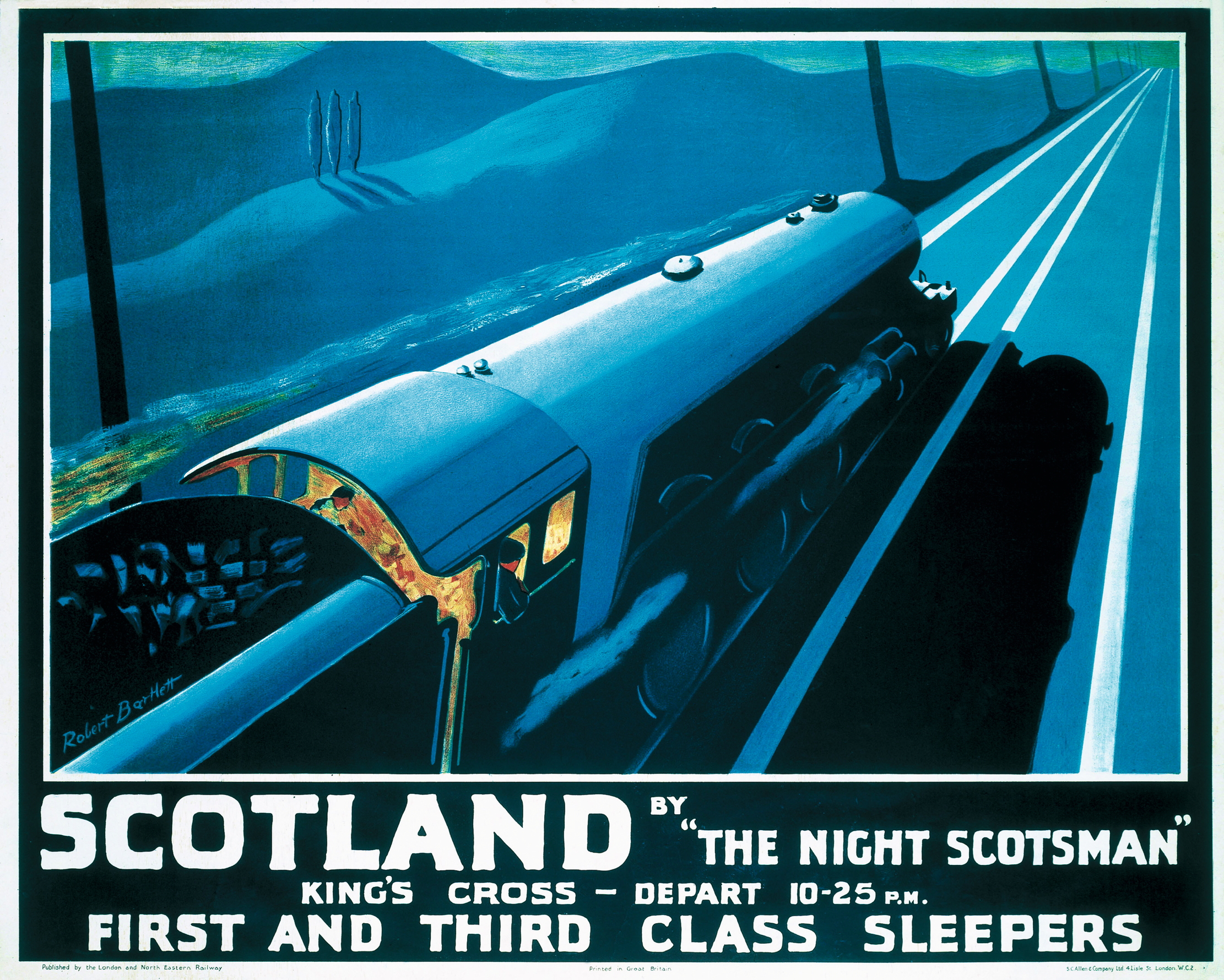

The distance from London to Inverness is only 443 miles, that to Penzance a mere 255, yet it’s still possible, six nights a week, to travel by sleeper to the throat or toe of Britain — or to do the journey in reverse. The Americans pioneered the sleeping carriage, the Belgians created the legendary Orient Express, but within their modest radius, the British developed a network of astonishing complexity and made sleeper travel synonymous with adventure and romance.

The three surviving services — the Highland and Lowland Caledonian Sleepers and the Night Riviera to Cornwall — are among the last vestiges of a golden age immortalised in film, literature and art. Seasoned sleeper-goers look back nostalgically to when cabins were equipped with an opening window, gas fire and chamber pot — and that curious anachronism, a little suede pad and hook for your fob watch.

Lulled to sleep by the clickety-clack of wheels over jointed rail tracks, we’d wake to tea served in proper china, as Gavin Maxwell did one morning in 1956: ‘Was it tea for one, or two, sir?,’ the attendant asked, staring at Mijbil, who lay beside him on his back, head on the pillow, arms outside the bedclothes. Maxwell’s Iraqi otter was not the only being who found the sleeping car, with its ‘wonderful panoply of Western technology — its hot and cold water taps, its light switches, its attendants’ button’, sheer paradise.

Powell and Pressburger capture the magic in their 1945 classic I Know Where I’m Going!, with its surreal dream sequence in which the heroine, cocooned in her miniature bedroom on wheels, is transported through tartan hills to the strains of The Bonnie Banks of Loch Lomond as the Manchester to Glasgow night train speeds her towards the isles.

‘The geography of Britain makes a night on the sleeper the ideal length for a journey,’ says Rupert Soames, who once raised eyebrows when he tried to book his car onto Motorail using his student railcard, but later found himself running Caledonian Sleeper as CEO of Serco. ‘There’s something about going to sleep in one world and waking up in another that’s just not the same as driving up the M6.’

'Rich southerners could now bring their families, servants, silverware and pets to remote lodges, some financing their own station stop, others attaching waggons of coal from their English mines or transporting their bees to summer in the heather'

Dalwhinnie, Kingussie, Crianlarich, Rannoch, Carnoustie, Liskeard, Bodmin, Par, St Erth: the evocative litany drifts into the semi-consciousness as the traveller awakes to a foreign land. The sense of adventure is shared by Americans with matching luggage destined for Skibo Castle, tweed-clad sports-men heading for the hills, climbers poring over Explorer maps, couples celebrating their wedding anniversaries and families on holiday to the Cornish coast.

Even for sleeper regulars, the thrill of stepping from the maelstrom of a central London station into the convivial atmosphere of the lounge car, of being rocked to sleep wearing complimentary earplugs as the train rattles homewards and then pulling up the blind to the desolate grandeur of a Highland glen or the wooded combes of Cornwall never fades.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The Night Riviera from London Paddington takes the Great Western Railway’s (GWR) historic route through the West Country, crossing the Tamar on Brunel’s magnificent Royal Albert Bridge at 5.30am and arriving in palm-fringed Penzance by 8am. Saved from the axe in 2005, it was revamped in 1970s-retro style in 2018. At about the same time, Serco rebranded the Caledonian Sleeper as a hotel-type experience, with a ‘brasserie club car’, soft-shaded tweeds and en-suite ‘rooms’ with key-cards, some with double beds.

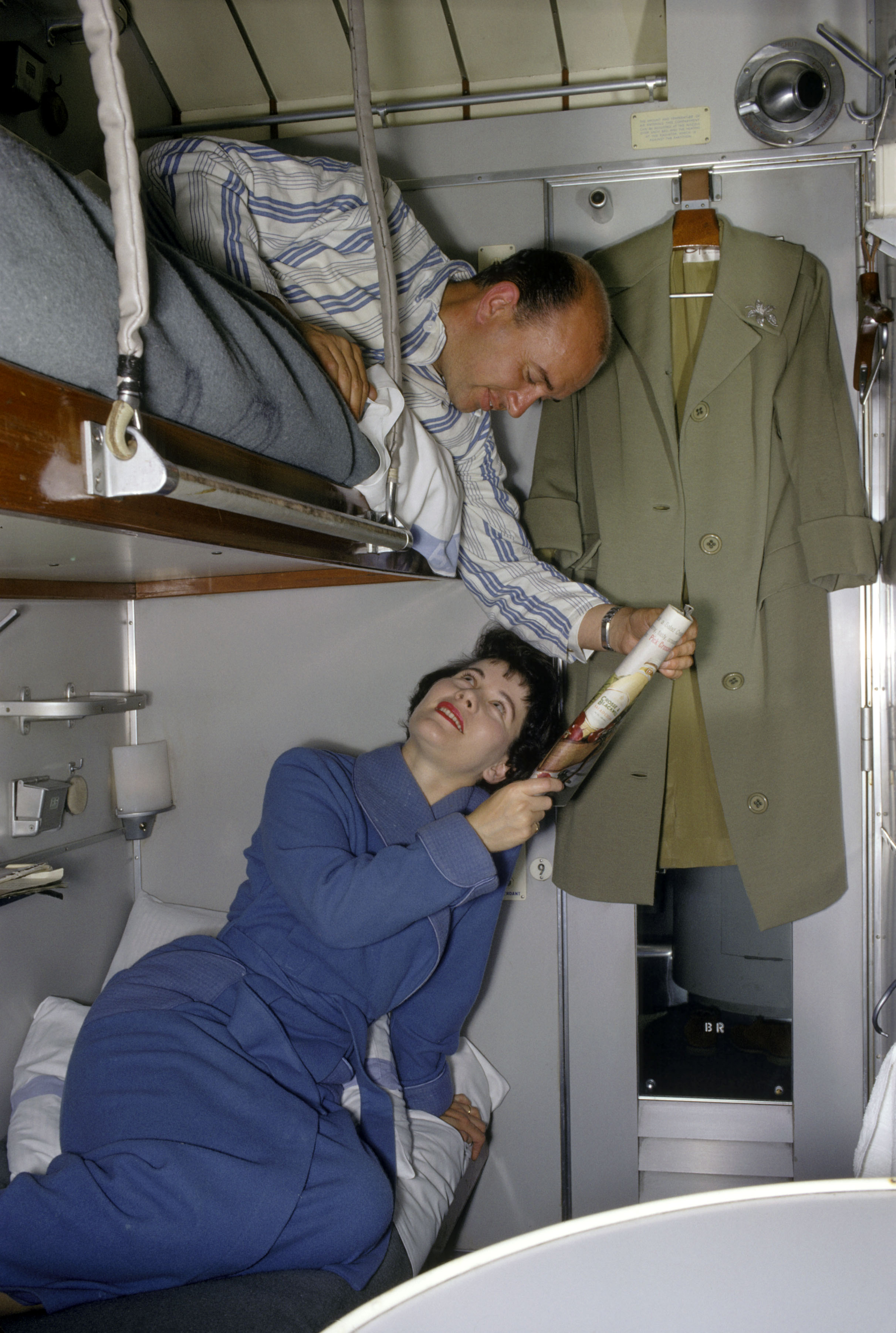

Now renationalised, the new Mark 5 trains are not without design faults — nowhere in your cabin to put anything; an intrusive ladder fixed to the bunks — but the bedding is softer and the dining-car ‘hosts’ serve proper meals made with seasonal Scottish fare, with a drinks menu to match.

For a taste of pre-war glamour, however, the Belmond Royal Scotsman is the choice, although a tour will set you back between £6,400 and £28,700. Resplendent in maroon-and-gold livery, the carriages — converted Pullmans named after birds and gems — include two marquetry-panelled restaurants, an Observatory Car, Dior spa and grand suite. As retired Baltimore banker Andrew Hartman observes, ‘a big attraction of a luxury train tour like this is that you can sleep in the same bed, instead of packing and unpacking in a succession of hotels, and you know you’ll be comfortable every night’.

Britain’s most opulent sleepers were rolled out by the London and North Western Railway in 1881. Modelled on the convertible French lits-salon, their carriages came complete with smoking saloon and en-suite compartments unholstered in ‘crimson and brown saladin moquette with matching crimson silk laces’. Travellers on a tighter budget could purchase a Peake’s Portable Sleeping Rest (basically a stretcher) from Harrods or travel in one of the GWR’s ‘dormitory cars’.

In 1894, the North Eastern Railway introduced the design we recognise today, with sleeping compartments opening off a corridor. Not all welcomed the transverse bunks, which carried you ‘Like a timber broadside in a fast stream,’ as Norman MacCaig later complained in his poem Sleeping compartment.

Central to the development of British sleepers was the so-called Highland Season, the August migration that fuelled the rivalrous railway companies’ Race to the North. Rich southerners could now bring their families, servants, silverware and pets to remote lodges, some financing their own station stop, others attaching waggons of coal from their English mines or transporting their bees to summer in the heather.

Sir John Gielgud’s mother, Kate, daughter of the artist-haberdasher Arthur Lewis, described the thrill of the train journey from London. The family travelled in its own carriage, comprising two first-class compartments, one second-class, a lavatory and baggage waggon. After breakfasting at Perth, they continued for 10 hours via Aberdeen, picnicking as the train puffed on to Inverness, where they were met by their coachman for the final leg of the journey.

As late as the 1960s, eight overnight trains ran from Euston to various destinations, six from King’s Cross and one from St Pancras. Even Beeching concluded that there was good reason to suppose that sleepers between London and Scotland could be ‘improved and increased’. The next few decades saw the introduction of various new designs, but competition from motorways, airlines and faster day trains did it in for many routes and 1997 privatisation killed off the much-lamented Motorail. The notable exception was the Fort William service — the so-called Deer-Stalker Express — which was saved after a spirited campaign in 1995.

Operating on the West Coast Main Line, the Highland and Lowland trains are famous for dividing as their passengers sleep into sections bound for Fort William, Inverness, Aberdeen, Edinburgh and Glasgow. These dawn uncouplings can cause problems for cabin crawlers, as one lady discovered after coupling up with a stranger in the lounge car and retiring to his berth. In the morning, as her husband awaited her at Pitlochry, she found herself alighting at Aberdeen.

Many a friendship or an unlikely bond between strangers has blossomed in the relaxed atmosphere of the lounge car as the train rolls through the night. ‘Heading north, I always try to be in bed before Preston,’ says Lochaber-based MP Angus MacDonald, adding that, without the sleeper, it would be impossible to represent the West Highlands. ‘The staff are largely Highlanders and, off-season, you can still experience that old club-like camaraderie, but tickets are now difficult to get at short notice as the trains are fully booked.’

Holiday-makers have always been the lifeblood of the sleepers and today’s well-heeled tourists are prepared to pay a lot. Regulars may miss the old days, but they should be glad that this most civilised mode of travel survives. Contrary to expectations, British sleepers are flourishing. For once, Beeching was right.

Mary Miers is a hugely experienced writer on art and architecture, and a former Fine Arts Editor of Country Life. Mary joined the team after running Scotland’s Buildings at Risk Register. She lived in 15 different homes across several countries while she was growing up, and for a while commuted to London from Scotland each week. She is also the author of seven books.