The enduring allure of menus from ancient civilisations to modern day, via the revolutionary France

As time capsules offering a unique glimpse into our appetites, menus have always been highly collectible, finds John F. Müller.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

If you are the sort of person who attends corporate or City dinners, you have probably brought home at least one menu of a certain type over the years: a folded piece of flimsy card with a shield on the front and, inside, a bill of fare in Times New Roman (‘Pea and Mint Soup, Duck and Something Apparently Fancy, Sherry Trifle, Coffee and Mints’). In themselves, these menus represent neither a flowering of the gastronomic art nor art itself. However, taken as part of a long and colourful tradition, they become much more interesting.

To be handed a menu is, ideally, to be handed a map of the culinary world that a restaurant or a (very smart) host is about to spread before you. They offer a unique insight into a nation’s gastronomic development: each tells a story, revealing not only the dishes that once tantalised the tastebuds, but also the social customs, culinary trends and regional specialities of the time. No wonder they are so collectible, of interest to museums and private collectors alike.

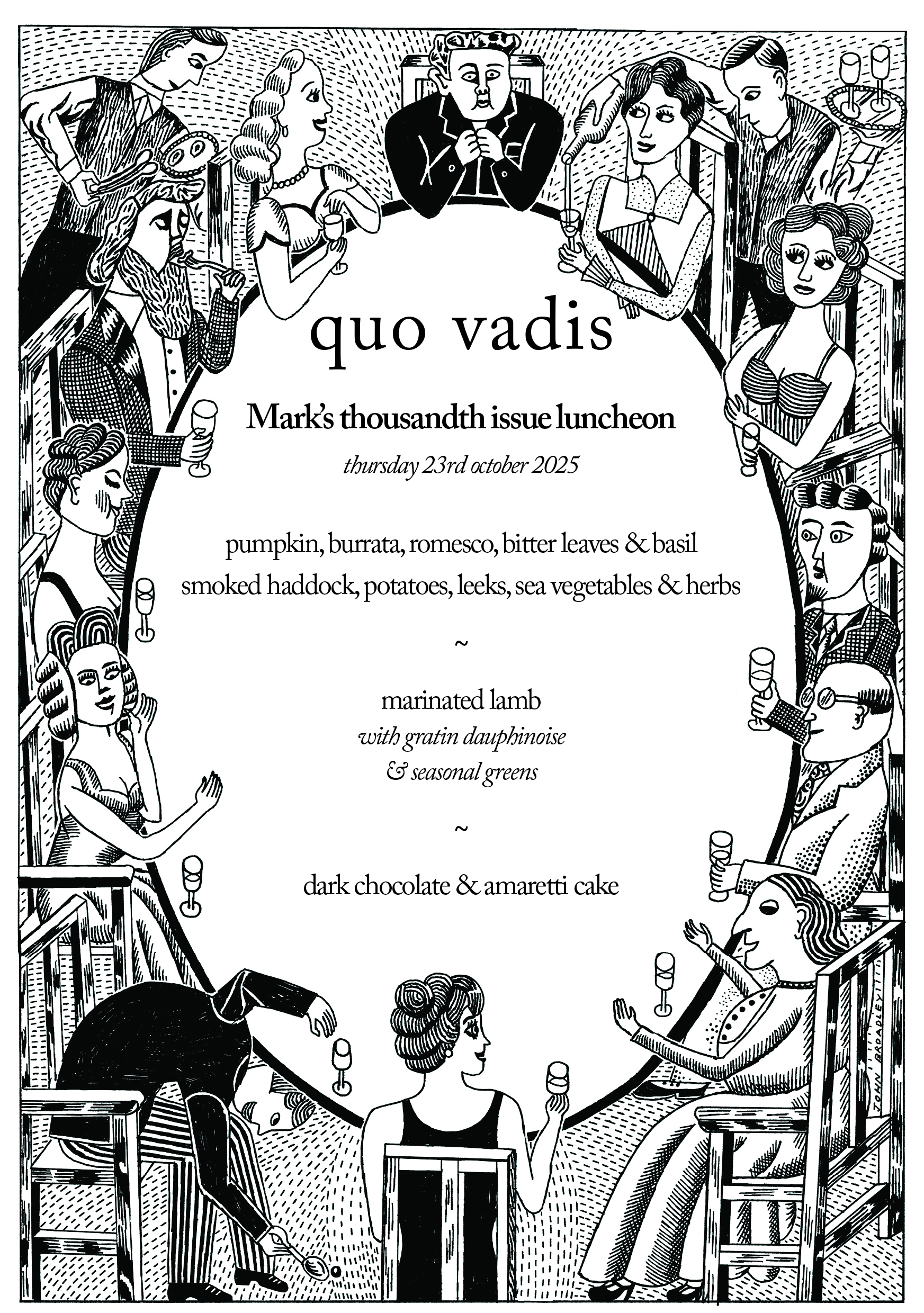

The Quo Vadis bill of fare for Country Life Editor-in-Chief Mark Hedges’s 1,000th-issue lunch.

When was the first diner presented with a menu? The earliest list of foods that we know of is an Assyrian stone tablet commissioned by Ashurnasirpal II in 879BC, which listed deer and oxen among the dishes at a banquet to celebrate his consolidation of power. However, its purpose was commemorative, rather than instructive; the lump of rock would have looked rather ungainly plonked on a damask cloth.

There have been bills of fare in some form ever since, yet they only really began to be seen widely outside of palaces and private houses during the French Revolution, when countless chefs who had previously catered for aristocratic households found themselves unemployed. The middle class had grown not only in importance, but also in wealth, so the preparation of many meals was outsourced to restaurants. This meant it became necessary to find a way of letting diners know what they could expect. ‘Menu’ comes from the French and is derived from the Latin minutus, which means small. Originally, menus offered choices on small chalkboards, known as à la carte. As printing spread, these boards were swapped for pieces of paper or card.

These felt engagingly personal, which played into an important part of the gastronomic revolution: being able to dine at your own table instead of communally and to choose your own dishes and drinks. As literacy rates rose, so did the quality of printing. With the process also becoming cheaper, a restaurant or inn could afford to have pre-printed cards made with its own headings and later filled in by hand (or with a typewriter) in house with the dishes of the day. We know that, at Italy’s oldest hotel, the Grand Hotel Porta Rossa, dinner consisted of sea bream, leg of lamb, salad and ice cream with assorted fruits one night in 1895 (doubtless it is the handwriting of a waiter that informs us of this delightful repast). Lunchgoers and diners would pocket these as mementos, a practice onto which shrewd restaurant proprietors soon caught, employing designers to create memorable menus.

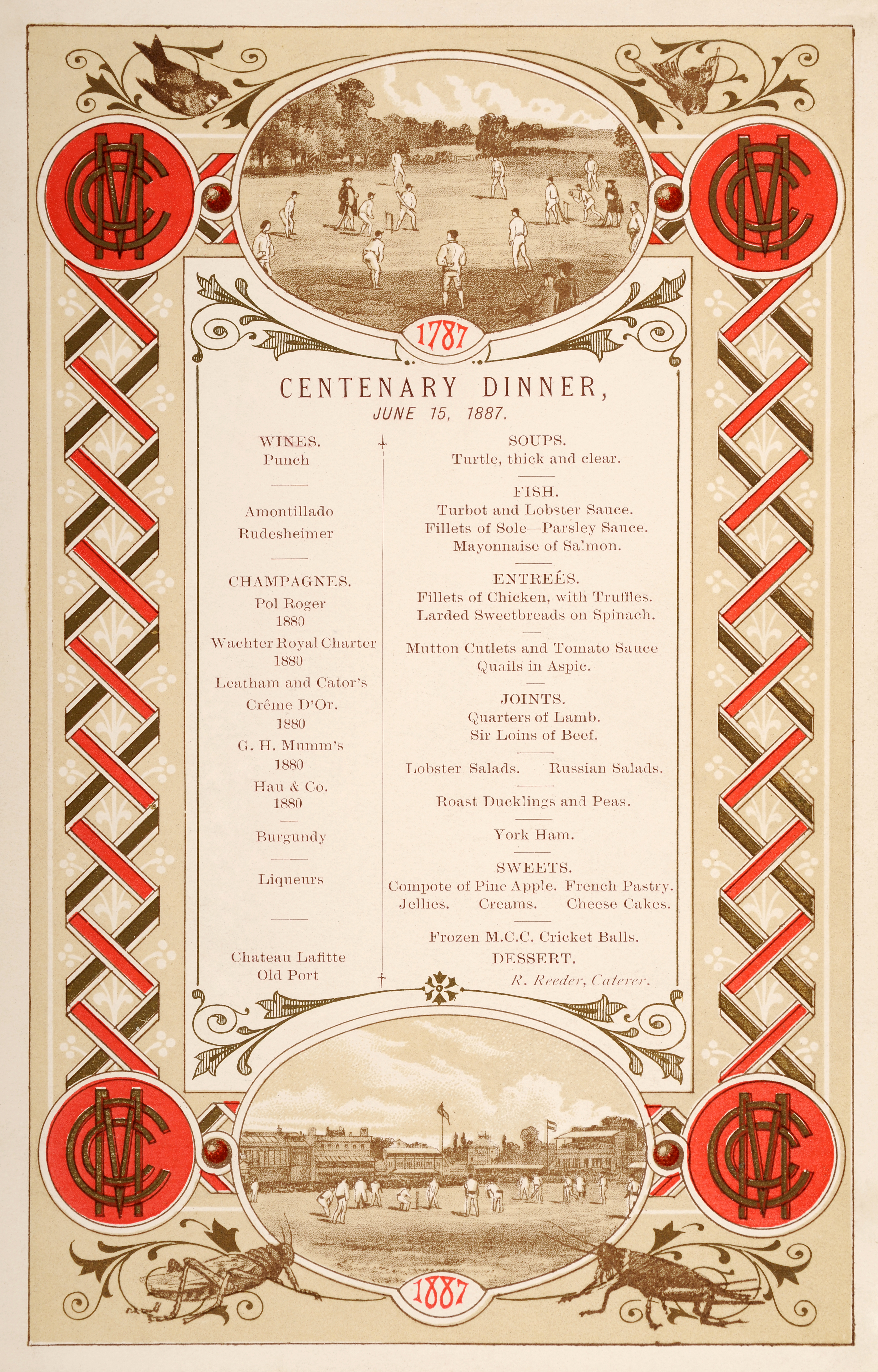

One hundred not out: turtle soup opened the culinary batting at the MCC Centenary Dinner at Lord’s, on June 15, 1887.

After the Revolution, French chefs travelled across the globe to serve in both private homes and public restaurants, leading to a standard of food presentation recognisable throughout the Western world — and a certain likeness between menus in destinations ranging from America to Germany. Early menu cards, printed up to about 1860, are stiff and single-sided, often with a simple decorative border and a symbol at the top (or the coat of arms of a private host). Menus in some restaurants, especially in the USA, could be voluminous, featuring close to 100 items, but more discerning establishments kept choice to a minimum, reflecting the cost of refrigeration and the limited number of crop varieties. Every menu tells a story: anyone who could produce an iced dish for pudding, no matter what the time of year, was showing off.

Although schedules of food and speeches at banquets have doubtless always been unofficially collectible, in the 1880s specifically commemorative menus were introduced, designed to serve as souvenirs. Embossed and cut to resemble lace handkerchiefs, emblazoned with heraldry, printed with decorative borders and scenes depicting royal residences, they could be remarkably elaborate, especially if they were created to mark a City of London or regimental dinner. Later, it became the custom to have those who dined together sign each other’s menus, lending them even more clout; a 1956 banqueting menu signed by Mao Zedong marking the first Pakistani state visit to China sold in 2023 for $275,000 (shark’s fin and roast duck were among the dishes served).

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

In the early 20th century, emerging steamship companies employed artists to create mermaid-bedecked menus commemorating crossings and, back on dry land, otherwise straitlaced Edwardians indulged in menus adorned with scantily clad ladies. A 1910 diplomatic dinner in Paris, sensibly heralded with the arms of the King of the Belgians, also featured Marianne (the personification of France) decorously straddling Champagne bottles and grapes as she proffered a glass to the diner. What exactly the entertainment was going to be for that dinner is anybody’s guess.

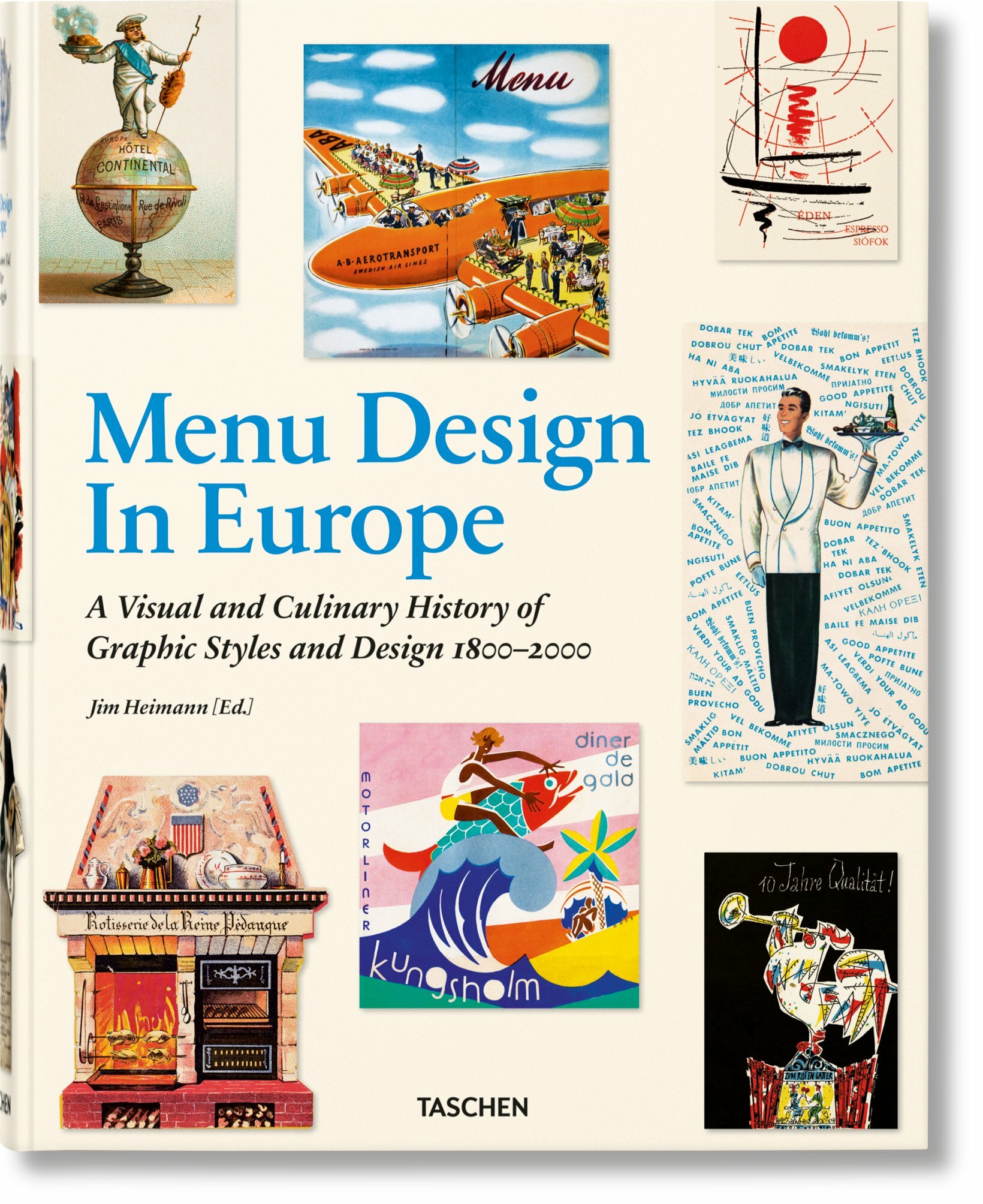

Two centuries of dining are celebrated by Taschen’s 'Menu Design In Europe' (2022).

Two World Wars passed menu design by almost entirely. However, the American military went to great lengths to supply traditional holiday food on certain festive occasions, printing menus for GIs to send home (not least to reassure their families that they were being properly taken care of). Both before and after the Second World War, a number of British luminaries turned their hand to playful menu design, including Eric Ravilious, who designed a menu for the Double Crown Club at the Café Royal 1935, and Edward Bawden, who worked closely with Fortnum & Mason — one of his 1950s designs for the store shows a lion trying to eat a wicker hamper whole. For those without the foresight to hang on to a Bawden menu at the time, these are showcased in The Mainstone Press’s charming Entertaining À La Carte, alongside an essay by the Fine Art Society’s Peyton Skipwith. Highly recommended also is Taschen’s superlative Menu Design In Europe: A Visual and Culinary History of Graphic Styles and Design 1800–2000 (Taschen, £50).

Today’s collections of menus come in all shapes and sizes, from the personal to the academic: the state and university library at Dresden in Germany now has an archive dedicated to all things culinary, with an emphasis on historic menu cards. The collection, which has been compiled over 15 years, is enormous: more than 50,000 items, many of them from private collectors. It includes one of Elizabeth II’s menu books, used by her chefs to note down suggested meals for her; at one point, spaghetti bolognese has a line through it, replaced by omelette aux tomates. These menus from times gone by are not preserved in metaphorical aspic: The British-based, EU-funded Menu Museum’s online collection is free to access and provides much grist to the imaginative mill for contemporary cooks, nutritionists and writers. There is also a facility included by which the public can upload their own menus, making this a living archive in which all can participate.

Happily, the art of the well-drawn — and, therefore, covetable — menu is also alive and well. One of those leading the way is the artist John Broadley, whose playful illustrations for Quo Vadis in London are immediately recognisable. In the early days, he recalls, the restaurant’s menus were printed fresh every day, which must have resulted in a fair few going home with diners. Historian and illustrator Daniel McKay, meanwhile, has created menus for numerous occasions, notably for the coronation dinners of Cambridge colleges. ‘As a designer, there is no greater thrill than seeing a gravy-splattered menu being pocketed into a dinner jacket or folded and stashed into a handbag,’ he says.

This feature originally appeared in the December 31, 2025, issue of Country Life. Click here for more information on how to subscribe.