A good call: The red telephone box rings in 100 years

One hundred years ago, the first all-red telephone box, designed by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott, was installed in London. Deborah Nicholls-Lee lifts the receiver on a very British icon.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Pay a visit to London’s Covent Garden and you’ll spot an immediately recognisable quintet watching over the shoppers: five K2 telephone kiosks in splendid crimson overcoats. They are almost always thronged with people — not looking to make calls, but keen to photograph these icons of British design. The K2, Britain’s first all-red telephone kiosk, made its debut 100 years ago and, although it has since been eclipsed by mobile technology, its appeal remains undimmed. Tucked inside the arched entrance of the Royal Academy’s Burlington House in Piccadilly, W1, the original timber prototype (designed by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott) stands to attention. This stately telephone box marked a growing belief in the importance of good public design, making amends for its unpopular predecessor, the K1, a design Eastbourne Council in East Sussex deemed so ugly that it thatched its seafront boxes, only to create a hideous hybrid: a concrete kiosk in a wig.

The K2 had loftier aspirations, taking the cuboid form and domed roof of the family tomb designed by the architect Sir John Soane as its inspiration. Each side featured a Tudor crown, which doubled as ventilation, and the teak door had a handle of nickel-plated bronze. ‘The K2 was the distillation of the essence of Classicism’ and responded to the perceived ‘chaos, degradation and unbridled individualism of the Victorian city,’ declared the architectural historian Gavin Stamp in his 1989 book Telephone Boxes. ‘It was a rare and special moment in British history, when both public authorities and industrial concerns strove to commission designs of high quality. Variety and showiness were eschewed in favour of uniformity, reticence and elegance.’

The old post office with an early style telephone box in Tyneham.

A group of people gather around a police public call box in London, which had been surrounded by sandbags for protection during World War Two.

The K2 demonstrated huge attention to detail, featuring a parcel shelf, ashtray and mirror. Coins were inserted in the ‘A’ slot, and change was given via ‘B’. Children found it irresistible to nip inside and push the B button in the hope of retrieving a coin or sweep the collecting tray with their fingertips. My own father-in-law was one of them. ‘On one occasion, we got a half crown,’ he recalls, still savouring the victory. A hefty telephone book on a chain had pranksters targeting the silliest surnames, whereas a 1950s craze for ‘phone box stuffing’ involved piling in as many people as possible. The record? Twenty-five.

However, the red kiosks were by no means an immediate hit. ‘When the first phone boxes were painted the true Post Office red, there was a bit of a stink, especially in rural communities: they were a little bit of a blot on the landscape,’ says Carl Burge, whose Norfolk-based business Remember When UK has been restoring vintage telephone kiosks for 25 years. A concession was made for areas of outstanding natural beauty by painting the glazing bars battleship grey. However, joyful red — selected by the Post Office so that the kiosks, so crucial in an emergency, were as easy to identify as post boxes — triumphed in the end, winning a place in our hearts. ‘Now, we praise them when we see them all fully restored and looking glorious,’ observes Carl.

In a survey conducted by Kingston University in 2015, the K2 telephone box was voted the best British design by 39% of participants, beating the Routemaster double-decker bus, the Spitfire and the Rolls-Royce. ‘They are so quintessentially British, aren’t they?’ remarks Mr Burge. ‘These things used to be on every street corner. It was our way of communicating. They’ve been through the war; they’ve been through good times and bad times. If these phone boxes could talk, what a story they’d tell.’

In an age of mobile phones, many telephone boxes have found new uses.

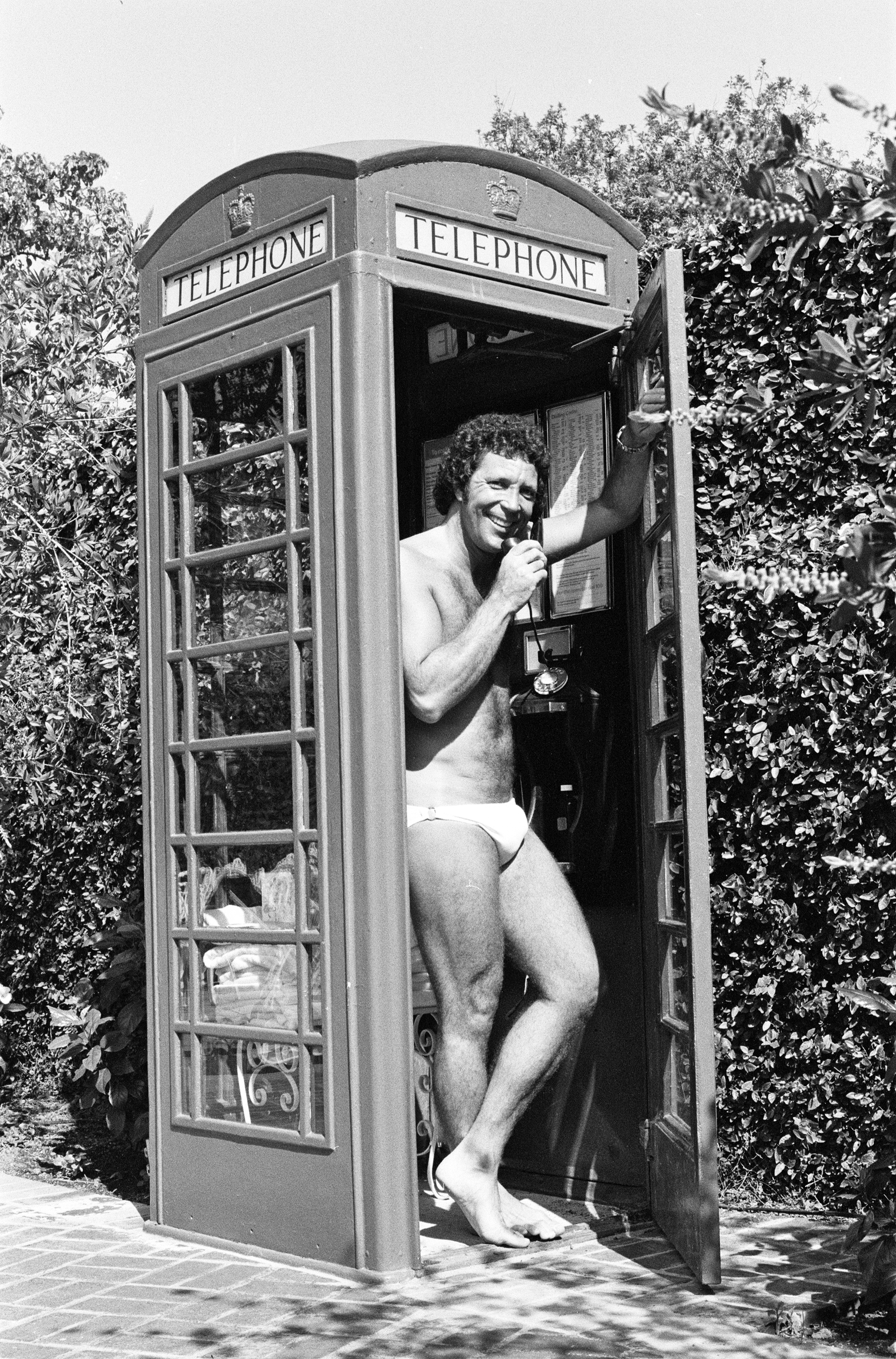

Such was the phone boxes popularity that Sir Tom Jones installed a phone box that once stood in the Welsh village of Pontypridd in his Californian mansion in the 80s.

Although handsome, the K2 weighed in at a hulking 1¼ tons, so variations soon followed. The cream and red concrete K3 (1929) was too brittle to enjoy longevity and its lightweight lookalike, the K5 (1933), was scrapped before it made production. Between them, the chunky K4 (1930), nicknamed the vermillion giant, asserted itself, replete with a post box and stamp vending machine, but its size and the need for access to both front and back required a rethink. The most successful was the K6, introduced in huge numbers as part of George V’s Silver Jubilee celebrations and 90 years old this year.

One of its biggest fans is Paul Bottomly, who, since 2019, has photographed and catalogued 6,600 kiosks as part of the K6 Project, a personal mission to visit almost every K6. His quest has taken him from the Warwickshire village of Withybrook, not far from his home, whose phone box first caught his eye, to the Outer Hebrides (‘It felt like I was on the edge of the world’). ‘For me, it’s looking back at a simpler time,’ he says.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Pop stars from David Bowie to One Direction have also expressed enthusiasm for this scarlet patrimony, featuring it on their album covers. Synth-pop band OMD even made a Merseyside phone box its temporary office, dedicating its 1980 song Red Frame White Light to it. The public uproar when, in 2017, the phone box was removed saw it reinstated within weeks. Cinema, too, has paid tribute to the phone box, particularly in the 1980s. In Gregory’s Girl (1981), directed by Bill Forsyth, it enjoys a brief cameo as a changing room, but, in his comedy-drama Local Hero (1983), Forsyth brought it to the fore, making a lone kiosk in a fictional village on Scotland’s west coast an oil executive’s only line of communication with his Texan office — a reminder of its sanctity in times past.

Lest we idealise the phone box, John Cleese’s comedically frustrating encounter with a series of poorly functioning phone boxes in Clockwise (1986), directed by Christopher Morahan, reminds us that it was not without flaws. It was during this period that the red kiosks were first threatened, when the newly privatised BT announced a modernisation programme that would replace them, misjudging the public mood. Even the advent of the mobile phone could not persuade people to part with their red phone boxes and, in 2008, BT launched the Adopt a Kiosk scheme, allowing councils to become their custodians for only £1. The renovated kiosks continue to serve their communities, but thanks to the nation’s ingenuity, are now defibrillator cases, for example, or cash machines, ice-cream parlours, galleries and libraries.

Restoring a telephone box involves ‘stripping it right back to its bare bones, to cast iron, as if it’s just come back from the foundry… then you’ll see the crowns and the castings come to life,’ explains Carl, who compares the meticulous process to ‘building bodywork on a classic car’. One of his projects now stands on the ninth tee of a golf course so patrons can order their bar meals. Others include a community seed exchange, a recording booth and a shower. Converting kiosks into loos he deems ‘a little bit barbaric’, but he was ecstatic when asked to renovate a K2 at the former home of Sir Giles Gilbert Scott: a full-circle moment that he describes as a ‘real honour’.

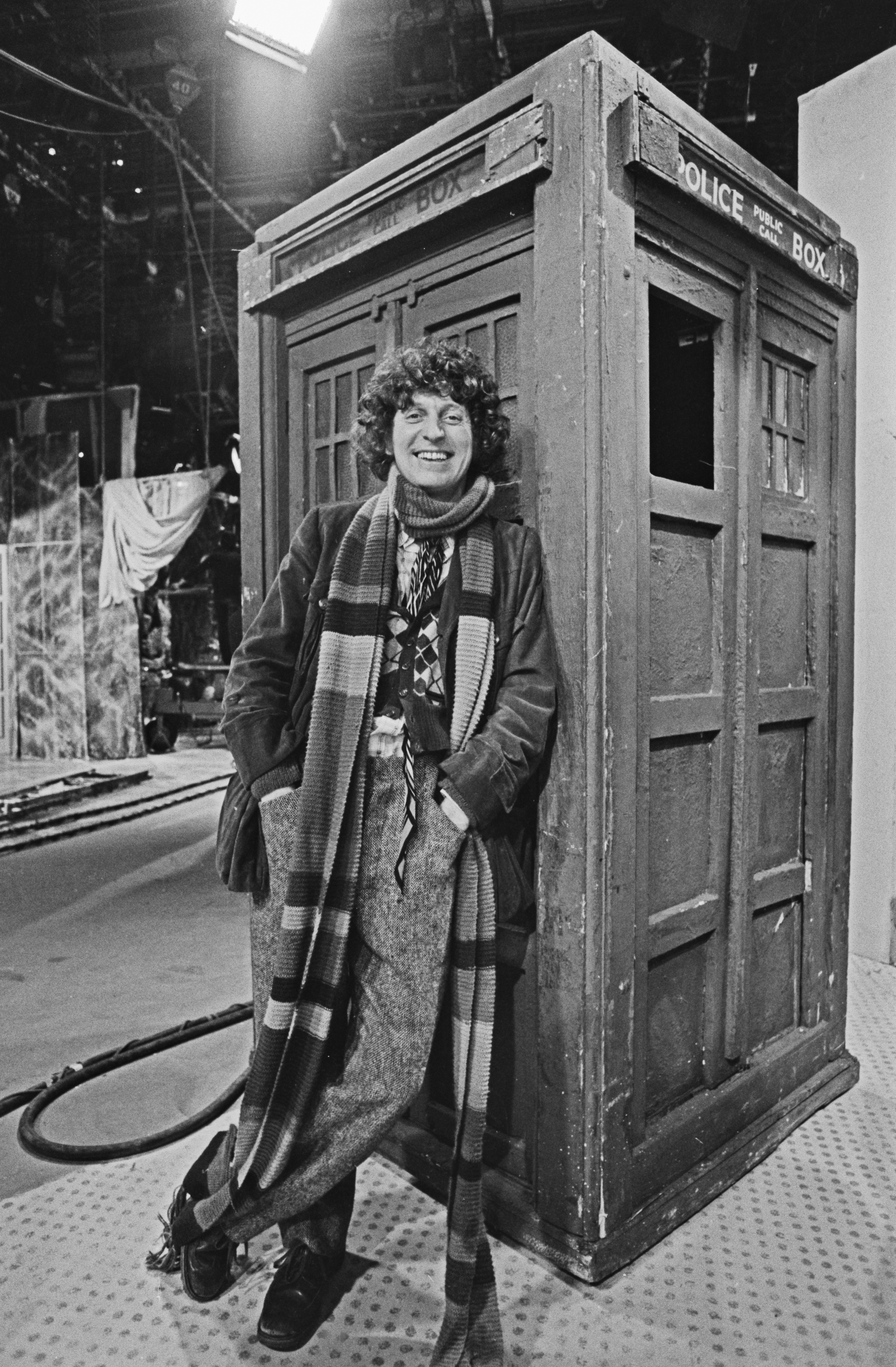

Phone boxes feature hugely in 'Doctor Who'.

They also have a Christmas card appeal.

The survival of our beloved red telephone kiosks owes much to the campaign group The Thirties Society (now The 20th Century Society), established in 1979 to preserve post-1914 patrimony. The organisation, whose founder members included Gavin Stamp, launched the Take it as Red campaign, which galvanised local authorities keen to keep, in Stamp’s words, these ‘visible symbols of Britain’.

‘The utilitarian need not be ugly,’ he insisted in Telephone Boxes. These kiosks show ‘how sensitive, dignified and, yes, beautiful street furniture can be’. As telephone boxes had no legal protection, the organisation successfully petitioned for the statutory listing of about 3,000 kiosks as miniature buildings. It’s been 40 years since the first kiosk was listed, a cream and red K3 overlooking London Zoo’s penguins, but the fight continues to conserve them. Only last year, villagers in Sharrington, Norfolk, successfully saved their red phone box by queuing up to use it to meet BT’s minimum requirement of 52 calls a year.

This feature originally appeared in the January 28, 2026, issue of Country Life. Click here for more information on how to subscribe.

Deborah Nicholls-Lee is a freelance feature writer who swapped a career in secondary education for journalism during a 14-year stint in Amsterdam. There, she wrote travel stories for The Times, The Guardian and The Independent; created commercial copy; and produced features on culture and society for a national news site. Now back in the British countryside, she is a regular contributor for BBC Culture, Sussex Life Magazine, and, of course, Country Life, in whose pages she shares her enthusiasm for Nature, history and art.