The real-life Manderley, and the other country houses that inspired Daphne du Maurier

The writer Daphne du Maurier was fascinated by the English country house. Jeremy Musson explores her evocation of these buildings with the help of photographs from the Country Life Image Archive and a series of specially commissioned drawings by Matthew Rice.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Few writers have captured the atmosphere of the English country house as acutely as Daphne du Maurier. The celebrated opening line of Rebecca (1938) — ‘Last night I dreamt I went to Manderley again’ — is followed by a description that is both particular and could also be anywhere in the British Isles. Evoking a route through trees that hints at a great house in the near — but not too near — vicinity, the narrator finds that ‘the drive wound away in front of me, twisting and turning’.

We never learn the young heroine’s name. She is simply the second Mrs de Winter, the Rebecca of the title being the first. But on her first arrival at this country house with its poetic name (Fig 1), she is an ingénue, quite unprepared for its underlying structures, hierarchies and rituals, from the fire in the library only being lit in the afternoon to the writing desk in the morning room being the proper station for the lady of the house to review the menus. However, her unpreparedness also leads her to notice things that would otherwise go unremarked: the sheer quality of pieces in a particular room, the care taken to match flowers in a vase to those seen through the windows. Du Maurier was able to evoke houses so well in her writing because she herself felt strongly about them; she loved them, cherished them and drew her stories out of their stories.

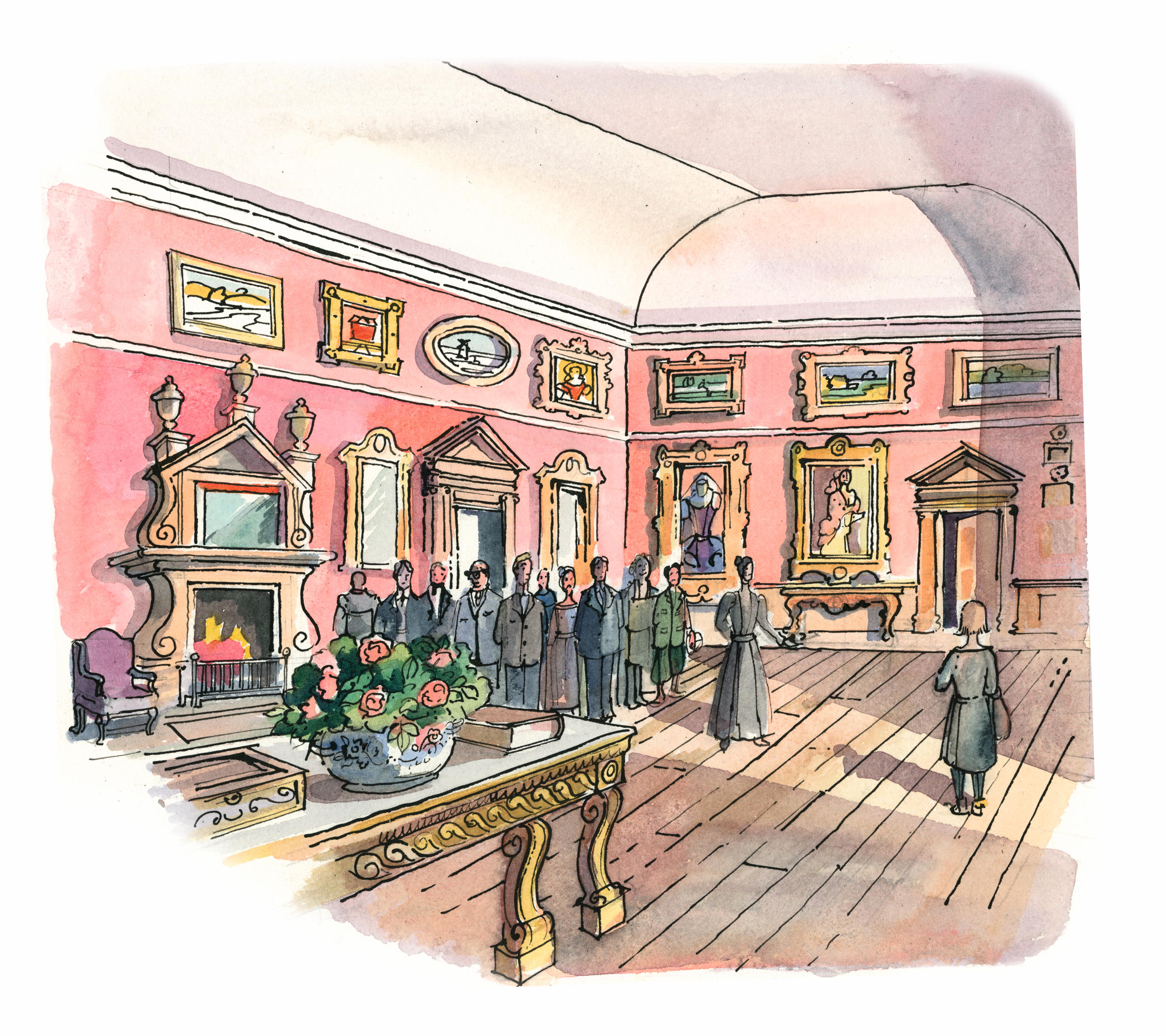

Fig 1: The moment when the second Mrs de Winter meets the terrifying house-keeper Mrs Danvers in Rebecca (1938).

Born in 1907, du Maurier enjoyed a sheltered, but Bohemian childhood. She was the daughter of actor Gerald du Maurier and actress Muriel Beaumont, who met appearing opposite each other in J. M. Barrie’s The Admirable Crichton. Her various homes throughout her life are deftly explored in Hilary Macaskill’s Daphne du Maurier at Home (2013).

From 1916, she lived in a handsome early 18th-century house in Highgate, north London, called Cannon Hall, for which her father eagerly sought out mid-Georgian furnishings. Daphne’s grandfather, Sir George du Maurier, was a Punch cartoonist and writer, best known for his novel Trilby (1894), which introduced the character of Svengali to literature, and the cartoon True Humility (1895) that made popular the expression ‘a curate’s egg’.

Fig 2: The River Fowey runs through the heart of du Maurier country, from Ferryside to Frenchman’s Creek.

In her early years, the du Mauriers often rented country houses in the summer, some of which appealed greatly to Daphne’s imagination, no doubt creating evocative references to old houses in works such as Rebecca, Frenchman’s Creek (1941), The King’s General (1946), My Cousin Rachel (1951), The House on The Strand (1969) and Rule Britannia (1972). She recalls 16th-century Slyfield Manor, Surrey, in her memoir Growing Pains (1977) and how the crooked stairs she climbed to bed created a sense of the ominous as she drifted to sleep, thinking: ‘Where had they all gone, the people who lived at Slyfield once?’

However, the ominous qualities of Manderley lay more in its people than its architecture: the dead first wife, the icily efficient housekeeper Mrs Danvers, first met in the great hall with all the servants lined up to greet their new mistress (Fig 6). The beauty of the house, its surrounding woods and proximity to the sea are appealing elements — even if the scale is at first daunting, as she gushes to the butler, who solemnly replies: ‘Yes, Madam, Manderley is a big place. Not so big as some, of course, but big enough… And the public are admitted here, you know, once a week.’

Du Maurier has described the ‘feel’ of the great house at Manderley as being modelled on Milton, Northamptonshire, the seat of the Fitzwilliam family, which she visited as a child in 1917. It was Mrs Fitzwilliam, an actress friend of her mother, who invited the family to stay when Daphne was 10 years old. As she later wrote in her memoir, ‘never before had I glimpsed anything so beautiful, so proud’.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

She was met at the door, before discovering ‘the magnificence of the great hall, the high ceiling, the panelled walls, and those portraits hanging upon them, men with lace collars, knee-breeches, coloured stockings’. There were breakfasts in the dining room attended by the butler: ‘A sideboard set with silver dishes, eggs and bacon, boiled eggs, kippers, even a cold ham’, an experience evoked in Rebecca, when the young Mrs de Winter is impressed and a little over-awed by the magnificence of such a breakfast.

Fig 3: Manderley, the family home of Max de Winter, the house inspired in large part by Milton in Northamptonshire, the setting that of Menabilly, Cornwall.

When Country Life published the first of three consecutive articles on Milton on May 18, 1961, it prompted her to write to the then Lord Fitzwilliam (a little older than her on her visit) recalling how Milton had inspired Manderley: ‘The interior, the rooms, the gallery, the “feel” if I may put it that way, of a large house was all that I remembered of Milton in those days of World War One.’ Indeed, in 1917, parts of Milton were being used as a military hospital and this finds its echo in The Progress of Julius (1933) when the millionaire Julius Levy, ‘had given his beautiful country seat for the wounded sons of England’ and ‘the drawing rooms had been turned into wards, the terrace and the gardens were sprinkled with bath-chairs and men in blue’.

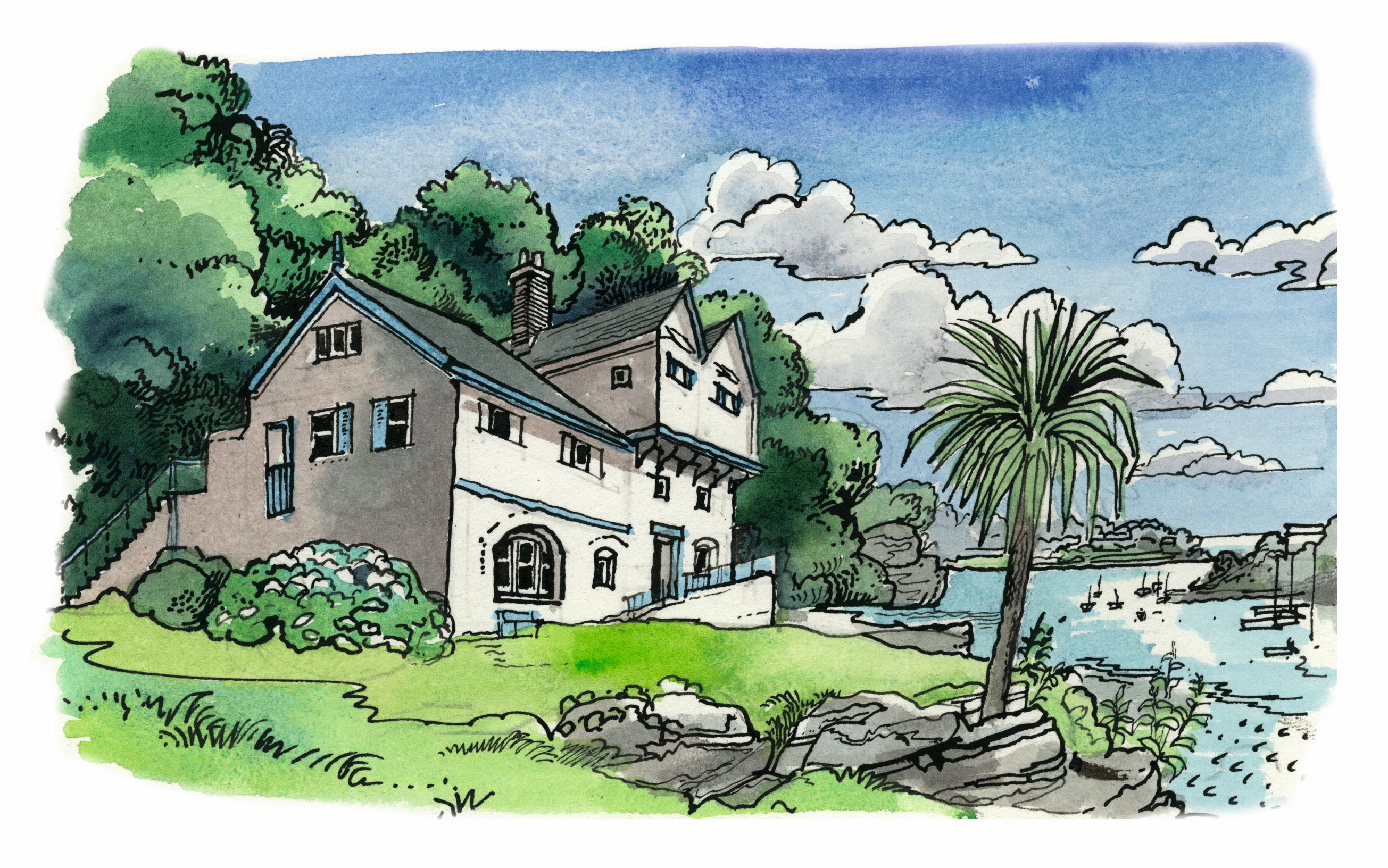

Cornwall and its hidden valleys, dark stone and rocky coastline became her spiritual home and is evoked in her book Vanishing Cornwall (1967). It is illustrated with photographs by her son, Kits Browning, who also made documentaries with her. In this book, she describes a family visit in 1926, when, crossing on the ferry to Fowey with her mother and sisters, they spot a curious part-house, part-boathouse built into the cliff. It is for sale and the family purchases it as a holiday home the following week. Recalling the impact of this unusual house, Ferryside (Fig 5), du Maurier wrote: ‘Here was the freedom I desired, long-sought for, not yet known. Freedom to write, to walk, to wander.’ She compared the feeling to that of a lover looking for the first time ‘on his chosen one’. Here she wrote her first successful novel The Loving Spirit (1931), inspired by the life of Fowey.

Fig 4: Menabilly, the beloved home of the novelist Daphne du Maurier and the setting for her stories.

The family’s summer retreat became du Maurier’s refuge. She often stayed there by herself and it was the place she learnt to sail (Fig 2). Ferryside was also where she was courted by army officer and keen sailor Tommy ‘Boy’ Browning, later chief of staff to Lord Mountbatten. He was knighted in 1946 as a lieutenant-general, so du Maurier became Lady Browning. The house was subsequently the home of her sister and then bought by Kits and his wife. His parents’ pre-war peripatetic existence led to many moves, including time spent in Alexandria, Egypt, and homes including the handsome Queen Anne Old Rectory at Frimley, Surrey, and gabled Greyfriars, near Aldershot in Hampshire, a 16th-century house, since demolished.

From the late 1920s, du Maurier’s Cornish circle included Foy Quiller-Couch, daughter of the author Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch. Through Foy, she became friends with traveller and author Lady Vyvyan of Trelowarren, younger wife of Sir Courtenay Vyvyan. Theirs was another romantically situated old house, much remodelled in the 18th and 19th century. Du Maurier recalled her first visit, ‘the library filled with books… a stable clock that struck the hours, then silence again, the silence of centuries’. She called it in her diary ‘the most beautiful place imaginable’… ‘the Last of England’ and wrote that she ‘wanted to weep and hide in its walls’. It was on a riding jaunt with Foy that du Maurier first visited Jamaica Inn, which inspired her novel of Cornish smugglers.

After the success of Jamaica Inn (1936), Rebecca (1938) and Frenchman’s Creek (1941), du Maurier found that, in 1942, she was able to afford to rent and repair the house of her dreams, the still mostly uninhabited Menabilly (Fig 4) in Cornwall. She wrote of ‘the sun warming the old dusty rooms… the scrubbing of the floors that had felt neither brush nor mop for many years’. Later, apparently on the advice of A. L. Rowse, she restored small-paned sash windows, in place of Victorian plate glass, transforming the character of the house. The grounds, the woods which encircled it, the path to the sea, the grotto and the boathouse all played their parts in her enjoyment of it, and she once said: ‘I do believe I love Mena more than people.’

Fig 5: Ferryside, the house where the du Mauriers holidayed and which inspired her story The Loving Spirit (1931). It was here that the author was courted by Tommy ‘Boy’ Browning, whom she married in 1932, and it was later home to her sister and then her son.

The house supplied the coastal setting for Rebecca and was the inspiration for The King’s General (1946), a story about a house called Menabilly, directly inspired by its history and the English Civil War experiences of the Rashleigh family. In 1824, a bricked-up room had reputedly been discovered at Menabilly with a skeleton of a young man sitting on a stool in the clothes of a Cavalier. The interiors of the house in the novel include a ‘long gallery, a great dark panelled chamber with windows looking out on to the court’, as well hints of the suffocating hiding place.

Although the image that directly inspired the story of My Cousin Rachel was a portrait of Rachel Carew that hung at Antony, the Carew-Pole family home near Torpoint, Cornwall, the stone house in the book also evokes Menabilly and older gentry houses of the county. Special reference is made to how the first glimpse of the house brought a sense of peace: ‘It was strange how the emotion and the fatigue of the past weeks vanished at sight of the house… It was afternoon, and the sun shone on the windows of the west wing, and on the grey walls.’

Fig 6: Narrator Philip Ashley and cousin Rachel — of the novel My Cousin Rachel (1951) — pore over designs for his gardens.

The narrator, Philip, feels the tug of his inheritance: ‘It came upon me strongly and with force… Those walls and windows, that roof, the bell that struck seven as I approached, the whole living entity of the house was mine, and mine alone.’ His cousin’s widow arriving from Italy claims to know the place only from her late husband’s description of it: ‘I’ve done it so many times, you know, in fancy. Everything was just as I had imagined it. The hall, the library, the pictures on the walls.’ She settles into English country life and enters into the landscape improvements with gusto, poring over books on gardening and plans in her boudoir (Fig 6).

In her widowhood, du Maurier moved to the old dower house of the Rashleigh estate, Kilmarth (Fig 7), a handsome, mostly 18th-century building on the south coast with a ‘glorious view of the bay’.

Fig 7: Kilmarth, to which du Maurier moved to after Menabilly and the setting for The House on The Strand (1969).

Kilmarth also became the setting for The House on The Strand (1969), one of her most successful novels, a stark and complex tale of a man taking a hallucinogenic drug to experience time travel. Here, too, she wrote the short story Don’t Look Now, later famously adapted as a chilling film. In her sixties, du Maurier set about various improvements, including the creation of a chapel in the basement. However, she would still brood about Menabilly and wonder if it had returned ‘to a sort of Rashleigh gloom, with all those frowning portraits on the wall’.

It is curious to realise that du Maurier, who loved houses so deeply, never really owned a house of her own. However, from her connection to the houses she knew emerged something deep and powerful, shaping and colouring stories that, in turn, shape our own imaginative responses to her fictions.

Acknowledgements: Kits Browning, Hilary Macaskill, Sir Philip and Lady Isabella Naylor-Leyland