'I first read this as a teenager and was open-mouthed at the sharp satire and the normalising of deep eccentricity': The books that the Country Life team return to again and again and again

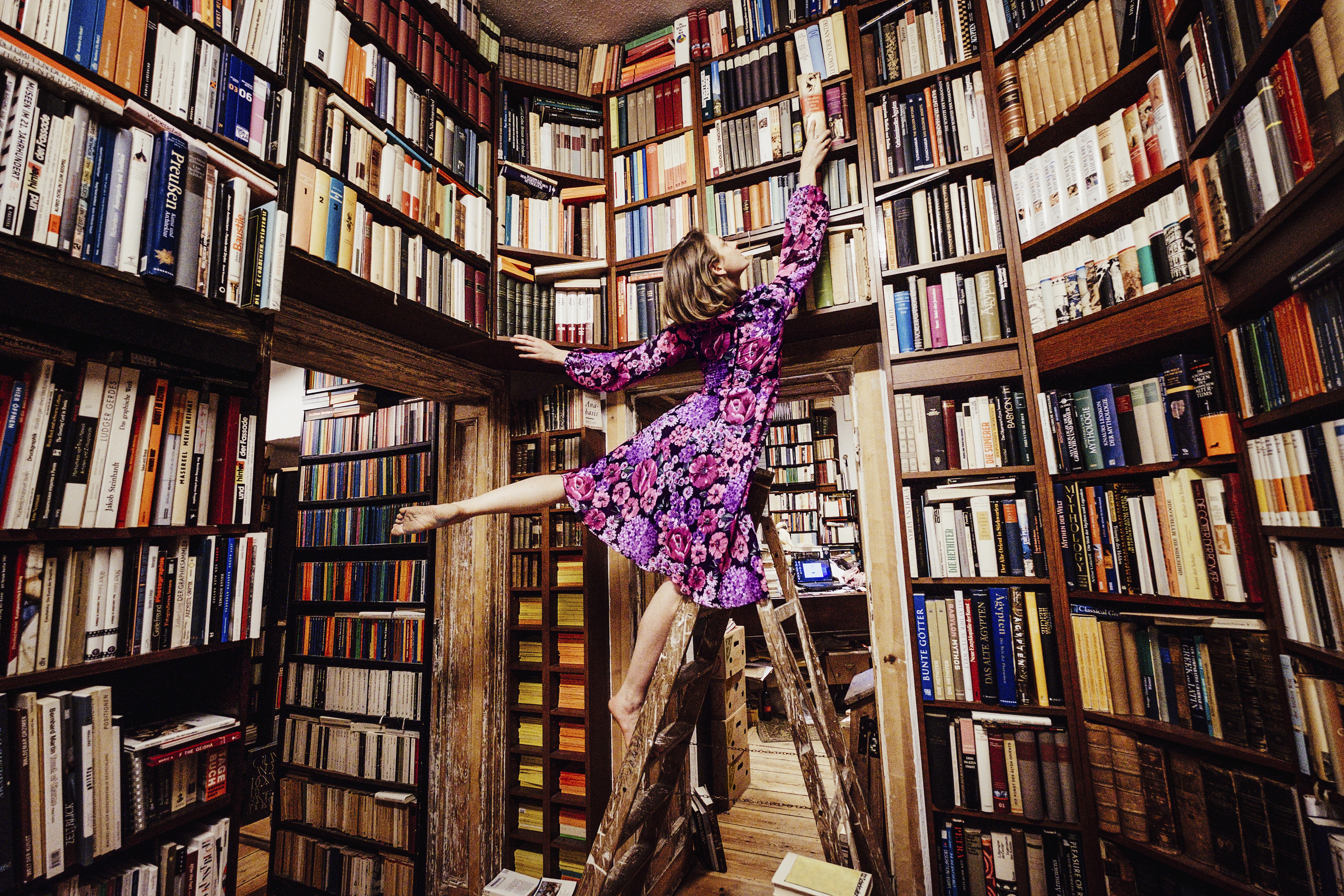

Have you made a resolution to read more in 2026? Members of the Country Life team reveal the fiction novels they've turned to time and time again.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The Rosie Project by Graeme Simsion

I’ve lost count of how many times I’ve picked up The Rosie Project, yet every re-read feels just as funny and moving as the first.

The story follows Don Tillman, a genetics professor who designs a questionnaire to find the perfect partner. What keeps me coming back? Don. Sharp, hilarious, tender, and entirely different from the usual bachelor you find in rom-coms.

It’s a book with that rare ability to make you feel almost every emotion at some point, while connecting you so deeply to the characters that they feel like old friends you feel fiercely protective of. At the same time, it’s the only book that’s ever made me chuckle, snort and weep — in public, on the Tube, no less (a cardinal sin in London etiquette). I’ll recommend it to anyone and everyone who’ll listen.

Flo Allen, Social Media Editor

The Pursuit of Love by Nancy Mitford

I first read this as a teenager and was open-mouthed at the sharp satire and the normalising of deep eccentricity and moved by its exposure of human frailty and its final pathos. This was no fairytale ending and when I realised it was semi-autobiographical it impressed upon me that, although things don't always work out, life is what you make of it.

Some images — the 'little houseless match' and Louisa making the best of dancing with an older man whose hair was receding like 'an eiderdown slipping off the bed' — have stayed with me forever.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Kate Green, Deputy Editor

The Secret Garden by Frances Hodgson Burnett

This was the first library book I returned late. It wasn’t tardiness, but a need to read it again straight away, accepting the 5p fine that was my (poor nana’s) fate.

It is beautifully written — understandable without being simple— and has a magical story that transfixes readers of every age. At its heart is its understanding of the beauty of Nature and Nature’s ability to transform. You can feel Mary, the central character, changing, chapter by chapter, with each visit to the secret garden. The threads of thought she formed in her previous life slowly disintegrate, becoming compost for her new self to grow from.

It is a book that proves that with a little tenderness, barren can become bountiful, be it a secret garden or a sickly child. It also proves that time spent in the garden can soften anyone’s edges.

Amie Elizabeth White, Acting Luxury Editor

The Leopard by Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa

‘If we want things to stay as they are, things will have to change.’ Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa’s The Leopard has often been reduced to one celebrated sentence, an almost Darwinian impulse to adapt in order to survive — so much so that an entire political doctrine, the Lampedusa principle, takes its name after the author. Yet, return to the book and there are many, deeper layers to it, which become more evident or poignant at later reads (and life stages).

Yes, it has a political message — although arguably, it suggests the opposite, that collapse is inevitable for the aristocracy, powerless when confronted with history, as well as, at a time of resurgent nationalism, lifting the veil on the realities of forging a nation and how there is nothing natural about the process. But this is also a novel about an island, Sicily, and its people, so trapped by their past and their culture that they are unable to change even if it means remaining forever steeped in their own misery. It’s about the solace of beauty (of women, but also landscapes and buildings) and the staleness of certain marriages (‘Of course, love. Flames for a year, ashes for thirty’). And perhaps, above all, it’s about the human condition. Mankind is drunk on self-importance, deluded with its own centrality, yet cannot escape its destiny: death and irrelevance. ‘We were the leopards, the lions; those who'll take our place will be little jackals, hyenas; and the whole lot of us, leopards, jackals and sheep, we'll all go on thinking ourselves the salt of the earth’.

Carla Passino, Arts & Antiques Editor

Oranges Are Not The Only Fruit by Jeanette Winterson

I always find something new in Jeanette Winterson’s Oranges Are Not The Only Fruit. It is a book that I first read at school and which became the subject of my degree dissertation and an obsession of my adult life. It is desperately sad and bitingly funny.

The unusual bildungsroman charts the protagonist’s realisation that she is gay while living with her Pentecostal adoptive mother, who is ‘Old Testament through and through’ and ‘deeply resentful Mary had beaten her to a Virgin birth’. Interwoven with fairy tales, it is a thoughtful novel that unravels like a coil of orange peel, always leaving you hungry for more. Based on many elements of Winterson's own upbringing, you’d be forgiven for assuming Oranges was autobiographical. Winterson’s reply to that very question was: ‘Not at all and yes of course.’ However, she did name her main character Jeanette.

Lotte Brundle, Digital Writer

The World is Not Enough by Zoe Oldenbourg

Zoe Oldenburg was born in St Petersburg in 1916, emigrated to Paris in 1925, and came to England in 1938 to study theology. In Paris, again, she lived as a painter, writing in her spare time. This was her first book — an instant success when it appeared (as Argile in France, 1946) and I first read it, at my father’s suggestion, as a bored teenager on holiday in Wales. I barely left my reading nest on the sofa. I read it again when my children were small, snatching quiet moments to escape to 12th century France and the forthcoming marriage between 14 year old Alis of Puiseaux and the even younger Ansiau, grandson of Galon the Hairy of Linnieres. The Third Crusade, a love story, adventure… Oldenburg draws one in. The writing is faultless, the descriptions utterly convincing. It is the perfect antidote to the modern world.

Tiffany Daneff, Gardens Editor

In Memoriam by Alice Winn

I’ve never truly understood the concept of being haunted by a book, until I read In Memoriam by Alice Winn. Her debut novel is both a visceral description of frontline horror and a poetic and heart-wrenching tale of forbidden love. It is 1914 and Henrich Gaunt and Sidney Ellwood — children ardent for some desperate glory — lie about their age to enlist. As the memory of their idyllic English boarding school life is replaced by the brutal reality of the trenches, it’s impossible not to be entirely consumed by their will they/won’t they romance.

I wept my way through this book on first read, and it still sends shivers down my spine just thinking about the tragedies which unfold. A poignant reflection of the loss of innocence and the complexities of life, this novel is also a testament to true love, which transcends all physical superficiality.

Agnes Stamp, Acting Deputy Features Editor

Bridget Jones' Diary, by Helen Fielding

The two books to which I return time and again seem to encompass the two sides of my personality. On the one hand is a novel about a family's cultural and intellectual inheritance, by a writer prone to snobbery and overthinking (Experience, by Martin Amis). On the other is a satire about a well-intentioned Londoner who makes too many mistakes.

Helen Fielding first wrote Bridget Jones’ Diary not as a novel but as a column. The Independent had asked her to write about single life in London — an offer she deemed too exposing — and so the character that would become a byword for hopeless romantics was born. Of course, Bridget is so much more than that: she is a producer and reporter (albeit, one whose first ever appearance on live television involved bearing her knickers while sliding down a fireman's pole), a fierce friend and a daughter to unfortunately complicated parents. She is also a modern-day Elizabeth Bennett — Fielding based her plot on that of Pride and Prejudice — and, if the soundtrack to the film adaptation is to be believed, 'every woman', too.

The original novel, published in 1996, still feels as funny and refreshing as it did when it first hit shelves, skewering a culture in which lads ruled and women's magazines told readers to watch their weight. Humble brag, but I have a knack for remembering quotes — being forced to learn poems off by heart in primary school will do that to a person — and still cannot find a book more eminently quotable than this one. Sorry, Shakespeare.

It helps, of course, that I have read it at least five or six times. But it is, more importantly, a tribute to Fielding and the fact that she brought phrases like 'emotional f**kwit' into the vernacular.

Will Hosie, Lifestyle Editor

Leave it to Psmith by P.G. Wodehouse

It’s a delightful love story. Within the embrace of Blandings Castle the cares and concerns of the world are firmly shut out and a cast of gentle characters battle against the wit of Lord Emsworth's secretary, the 'efficient' Baxter, surely the least threatening villain ever invented. Wodehouse's ability to turn a hilarious phrase never fails to amaze.

John Goodall, Architectural Editor

Cold Comfort Farm by Stella Gibbons

Far be it from me to compare myself to the New Yorker columnist Rivka Galchen, but we have both always been drawn to what she described in a recent essay as 'worlds in which catastrophes are reliably headed off'.

There is no more reliable disaster-averter on my bookshelf than Flora Poste, who goes to stay with distant relatives in Howling, a squalid (fictional) corner of Sussex, between the wars. The Starkadders of Cold Comfort Farm, who she takes it upon herself to drag screaming into the 20th century, are a note-perfect send-up of the sorts of overwrought rustics that London intellectuals were writing at the time: Lawrentian lothario Seth, Urk and his voles, Aunt Ada Doom menacingly brandishing a copy of The Milk Producers’ Weekly Bulletin and Cowkeepers Guide, Adam who sleeps outside and does the washing up with a twig... And, of course Big Business the bull, confined to a shed to stop him getting at Graceless, Aimless, Feckless and Pointless. My shoulders are shaking just writing this.

Emma Hughes, Acting Assistant Features Editor

Rosie is Country Life's Digital Content Director & Travel Editor. She joined the team in July 2014 — following a brief stint in the art world. In 2022, she edited the magazine's special Queen's Platinum Jubilee issue and coordinated Country Life's own 125 birthday celebrations. She has also been invited to judge a travel media award and chaired live discussions on the London property market, sustainability and luxury travel trends. Rosie studied Art History at university and, beyond Country Life, has written for Mr & Mrs Smith and The Gentleman's Journal, among others. The rest of the office likes to joke that she splits her time between Claridge’s, Devon and the Maldives.