Tate-à-tête: The National Gallery’s promise to grow its modern-art collection risks reopening old wounds

The National Gallery's announcement of a new wing and more modern art promises to reignite a historic rivalry with Tate.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

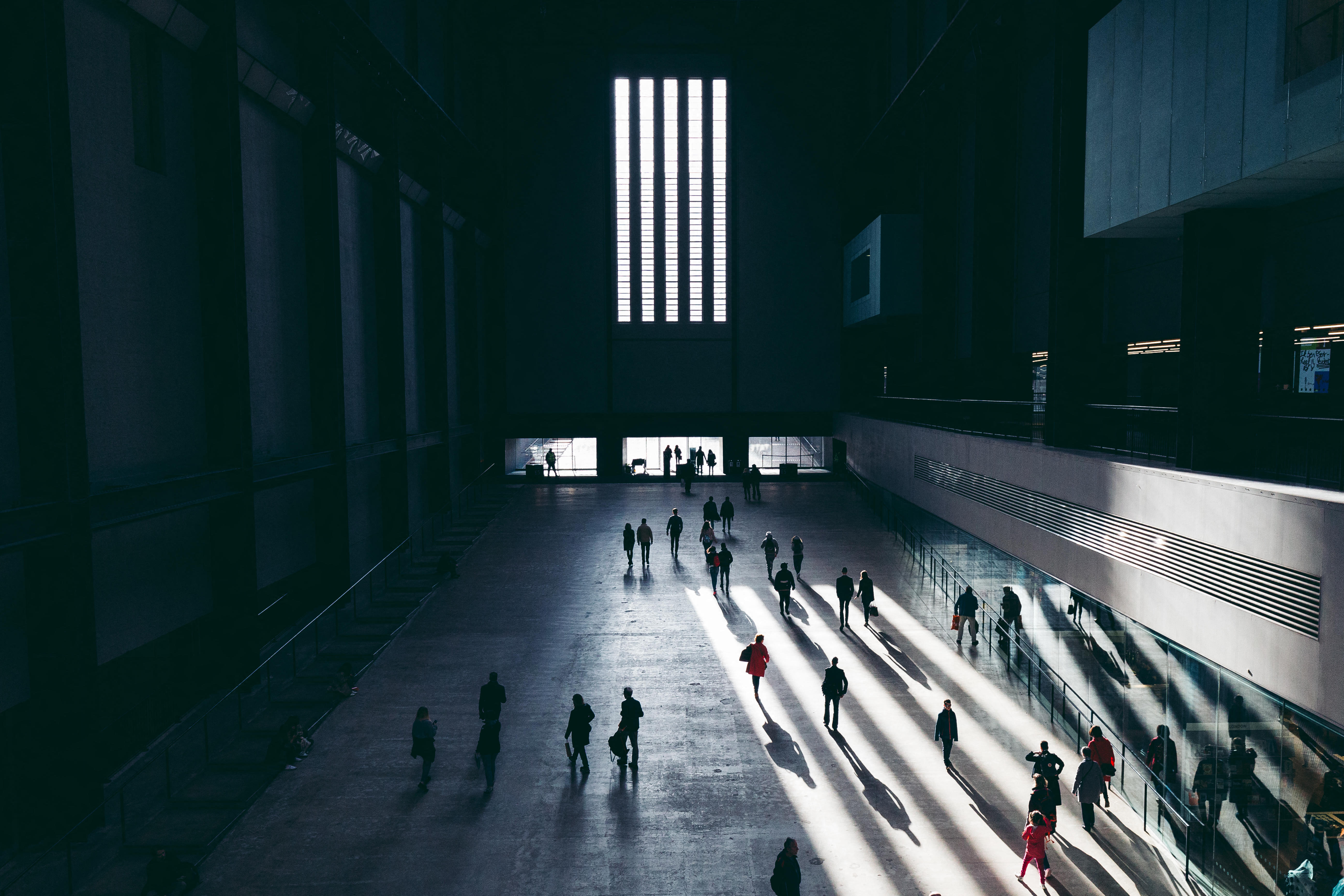

Last May, Tate Modern celebrated its 25th birthday with a gala in the Turbine Hall: a raucous affair attended by artists Sir Grayson Perry, Sir Antony Gormley and Dame Tracey Emin. Food was prepared by the River Café’s Ruthie Rogers and guests enjoyed a performance by the Pet Shop Boys.

As Hollywood stars Daniel Craig and Reese Witherspoon mingled over Champagne, Maria Balshaw, the director of the gallery, was fielding questions about Tate Modern’s future. Accounts for 2023–24 revealed yet another deficit budget approved by the trustees, ‘due to self-generating income not increasing at the same pace as the cost base post-Pandemic’. Last March, Tate Galleries cut 7% of its workforce.

When asked whether free entry to Tate Modern’s permanent collection could one day be revoked, Balshaw said ‘I very much hope not’; yet she didn’t rule out the matter. Acknowledging these difficulties, the group’s état major launched an endowment fund with the goal of reaching £150 million by 2030. This has been touted as ‘one of the most ambitious campaigns of its kind’, designed to support exhibition programmes, research and public reach. Charlotte Mullins, art critic and former editor of V&A Magazine, describes this target as ‘ambitious, but achievable’. Then came September.

News that the National Gallery had received not one, but two landmark donations, worth £150 million each, sent shockwaves through Tate’s upper echelons. Donations came from the Julia Rausing Trust and Michael Moritz’s Crank-start foundation and, with an extra £75 million from the National Gallery Trust, will enable the completion of a new building behind the Sainsbury wing by the early 2030s. Billed ‘Project Domani’, the extra space will allow the National Gallery to grow its permanent collection beyond the remit of pre-20th-century art — something its director, Gabriele Finaldi, has been keen to do for years.

Not only does this risk eroding Tate Modern’s hegemony on works post-1900, but it also places the museum front and centre of the cultural consciousness. The lark is ascending. The National Gallery enjoyed a wildly successful 2025, which saw the previous year’s 200th anniversary celebrations reach across to May, when the permanent collection was rehung to great acclaim and the Sainsbury wing finally reopened after years of renovations, granting the museum a new entrance.

Although Tate Modern is, technically, also on the rise (its visitor numbers, albeit down 27% from 2019, have been up year-on-year since 2022), it has struggled to win back its historic audience of young European visitors — who, Balshaw believes, have been negatively affected by Covid and Brexit. Since September 26 last year, the gallery has stayed open until 9pm each Friday and Saturday in the hope of wooing young viewers. This would prove to be one of Balshaw’s final moves for the museum: last month, it was announced that she would leave Tate Modern in April, confirming the upheaval previously hinted at by the gallery’s closest observers.

The recent rehang of the National Gallery's permanent collection was a resounding success according to critics.

Could Project Domani throw yet another spanner in the works? This remains to be seen. On the one hand, it seems entirely feasible that modern-art audiences might find an expanded collection at Trafalgar Square to be enough and no longer travel south of the river to see works by Dalí or Mark Rothko as often as they once did. On the other hand, it seems unlikely that the National Gallery would be able to add that many blockbuster paintings to its collection, given the astronomical costs of modern art. Michael Hall, former editor-in-chief of Burlington and Apollo magazines and Country Life’s erstwhile Architectural Editor, explains that ‘the National Gallery only ever buys masterpieces and notable Continental works from the early 20th century are extremely expensive’.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Despite the gallery’s recently inflated endowment, £375 million goes only so far when it comes to acquiring, say, a handful of Magrittes or Picassos. ‘I don’t think Tate will be having sleepless nights just yet,’ agrees Dr Mullins. Moreover, ‘the modern and contemporary wing will never be the dominant reason to visit the National Gallery — not when the Wilton Diptych, Stubbs’s Whistlejacket, Gentileschi’s self-portrait, Turner’s Rain, Steam and Speed and all those Impressionists are on the walls’.

One major advantage boasted by the Tate Galleries is volume: their collection is roughly 30 times the size of the National Gallery’s. Works have swapped hands between the two before (on which, more shortly) and it seems likely the National Gallery’s top brass would try to schmooze Tate or even come knocking at the door of its multiple museums in the hope of borrowing back pictures it had previously handed over.

Indeed, both institutions are historically intertwined: Tate exists in part because the National Gallery did not have enough storage space to accommodate the collection of 19th-century sugar merchant Henry Tate, which led to the creation of what was then the National Gallery of British Art, later Tate Gallery, now Tate Britain (Tates Modern, St Ives and Liverpool would come much later). At the time, the National Gallery bequeathed several works from its own collection, including more than 100 by Turner, to the young rival museum in Pimlico. In 1996, an agreement was drafted to cement the dividing line between Tate and National collections. The line was 1900: any European art from before that date would sit in the National Gallery and any after that would go to Tate Modern (which, although not yet open, had already been earmarked for development in the former Bankside Power Station). Tate Britain, meanwhile, would hold onto British art across both time periods.

These various boundaries were never cut and dried, however. They were indications; goalposts; even Tate was able to recognise the National Gallery’s right to acquire 20th-century works by artists typically associated with the 19th (think Cézanne or Renoir). Over time, the latter has nimbly circumvented the agreement’s finer points: in the early 2000s, it hosted an artist-in-residence scheme inviting contemporary artists to show their work alongside the permanent collection and has partnered, over the years, with Richard Long, Paula Rego and David Hockney; in 2025, Ming Wong took the role.

Even when it comes to British art, ‘the National Gallery has never made its approach to collecting terribly clear,’ says Hall, allowing it to dip into waters typically seen as belonging to Tate Britain. Tensions between Tate and the National Gallery came to a head when the latter hosted a landmark Picasso exhibition in 2007. The press, then as now, agrees: it should have gone to Tate Modern. Now, the National Gallery’s promise to grow its modern-art collection has reopened old wounds.

'As time moves on, 1900 seems increasingly remote and less related to how we think about periods of history and art history... It is slightly frustrating to reach 1900 and then not go on'

Tate Modern has been struggling to attract visitors since the Pandemic, with numbers down 27% since 2019.

The press, however, has also pointed out that anyone surprised by these developments must have been turning a blind eye. The National Gallery’s ambitions have been ‘hiding in plain sight for years,’ wrote Michael Prodger in Apollo, reminding readers that the museum’s intention is to take viewers through ‘a history of painting’. Speaking on this matter following his appointment in 2015, Finaldi said: ‘As time moves on, 1900 seems increasingly remote and less related to how we think about periods of history and art history... It is slightly frustrating to reach 1900 and then not go on.’

How should the National Gallery go about building its new collection? ‘The relationship between art’s historical past and the present is an important one for most artists and it will be fascinating to see how the new collection at the National Gallery is shaped,’ says Dr Mullins. An approach that illuminates these perspectives would also propose something quite different to ‘Tate’s forward-looking approach,’ she believes: ‘our past informs our future, so why not hunt out artists who explore this fully, such as Mickalene Thomas, Kerry James Marshall and Hew Locke?’

One should remember that, more than being rivals, Tate Modern, Tate Britain and the National Gallery are first and foremost public institutions. ‘All receive funding from the Department for Culture, Media & Sport,’ says Hall, ‘and they communicate closely with one another.’ With at least five years to go before the National Gallery unveils its new wing, Tate Modern still has time to recuperate and restrategise. Sources close to both suggest that, although gritted teeth are to be expected, the National Gallery’s latest evolution is unlikely to devolve into a full-blown row. ‘It depends how silly the trustees wish to get,’ one says.

The architects shortlisted for Project Domani were announced last month. Among them are Farshid Moussavi, Foster & Partners and Kengo Kuma, with the finalist to be announced in April. The new wing will back onto Leicester Square in a spot currently occupied by St Vincent House, a Brutalist edifice due for demolition that the National Gallery acquired 30 years ago and which currently houses a hotel and office complex.

Londoners who have long avoided Leicester Square for anything other than film premieres hope that revitalising this patch of the West End will improve prospects for both the neighbourhood and the gallery within it. As the National Gallery prepares to build big, Tate Modern will seek to make the most of its own existing infrastructure — what one source calls the museum’s ‘gung-ho extension from 10 or so years ago’. The primary culprit here is The Tanks, open since 2016 and billed as providing ‘a permanent gallery for live art, performances and film and video work from the Tate collection’ — a status that, so far, the gallery has under-exploited. ‘They’ve fallen off the radar for most people,’ confirms Hall, but this creates an opportunity.

Dr Mullins, for her part, believes ‘the Tate Galleries need to concentrate on how to present their collection to an audience that filters the world through social media, rather than make the London sites any larger. Traditional displays of Modernist art on white walls are less enticing to Millennials and Gen Z than the immersive installations of artists such as Yayoi Kusama.’ As it stands, Tate Modern’s 2026 programme is one for the ages, with two blockbuster shows on Dame Tracey Emin (February 26–August 31) and Frida Kahlo (from June 25).

The Tate Galleries would do well to capitalise on this — and, from there, raise a lot more money.

Will Hosie is Country Life's Lifestyle Editor and a contributor to A Rabbit's Foot and Semaine. He also edits the Substack @gauchemagazine. He not so secretly thinks Stanely Tucci should've won an Oscar for his role in The Devil Wears Prada.