Make sure you don't skip these South of England art and history highlights

In our final instalment of Charlotte Mullins' fifty treasures series she journeys to the South of England and the Isle of White.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

At a gallop

Uffington White Horse, Oxfordshire

The 360ft-long artwork was made 3,000 years ago.

Every August bank holiday, a troop of eager volunteers descends on the Uffington White Horse, 10 miles east of Swindon, for a spot of weeding and whitening. Rechalking the 360ft-long artwork, carefully cut into the side of a chalk hill, has been happening every few years since it was made 3,000 years ago. During wars, plagues and drought, the White Horse has continued to gallop across the landscape, its slender body, beak-like mouth and streaming tail slowly changing shape over the centuries. Why was the Uffington White Horse made? No one knows. It is located close to an Iron Age hill fort, but may pre-date it. Did it define territory or was it an ancient fertility symbol? Or did it venerate the horses that were once thought to pull the sun across the sky?

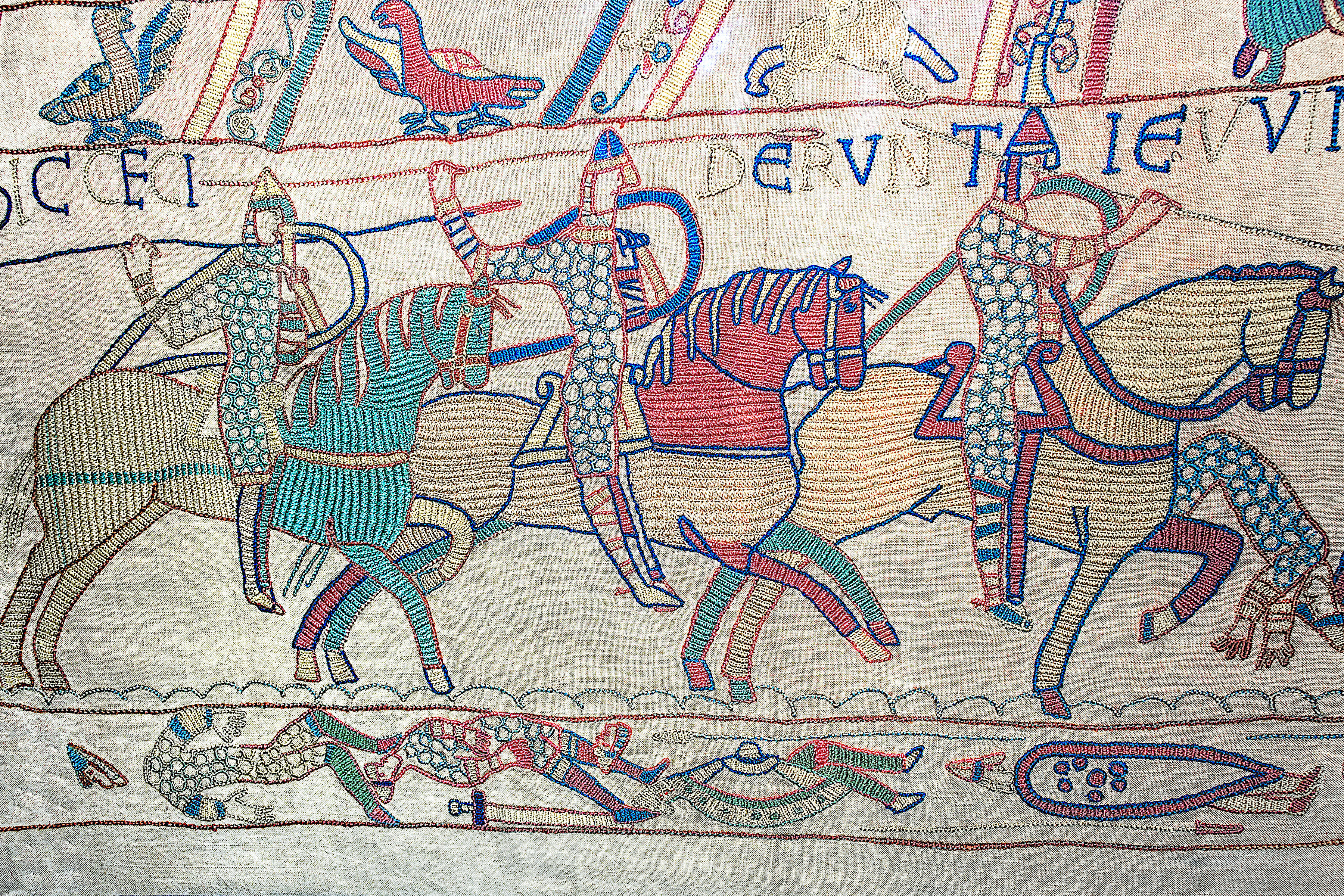

A stitch in time

Bayeux Tapestry Victorian copy, Reading Museum, Berkshire

A small section of the 230ft long Bayeux Tapestry .

There are three things you should know about the Bayeux Tapestry. First, it is not a tapestry, but an embroidery, carefully stitched on linen panels in Kent in the years following the Battle of Hastings in 1066, in time for the consecration of Bishop Odo’s Bayeux Cathedral in 1077. Second, it is an incredible 230ft long and features 600 figures, 200 horses and 55 dogs. The third thing is that, although the original is in Bayeux, France (until September 2026, when it will be on display at the British Museum in London), there’s a full-size copy in Reading Museum created by the industrious Elizabeth Wardle and her team of volunteers in the 1880s. The tapestry has several scenes set in France before the final showdown between Harold and William the Conqueror in England, suggesting a French commission. However, several show Harold in a favourable light, implying that an English artist was in charge of the overall design.

Forever and beyond

Alice de la Pole’s cadaver tomb, Ewelme Church, Ewelme, Oxfordshire

Alice de la Pole’s tomb is somewhat unusual.

Alice de la Pole’s tomb fits snugly between the altar and a side chapel in the church in Ewelme, a small village in Oxfordshire. It was completed in about 1475 and at first glance seems like a regular alabaster tomb that you might find in any provincial church. Peer through the architectural dais on which her effigy rests, however, and you will perceive a second skeletal figure. Known as a cadaver tomb, this is the only one of its kind featuring a woman in Britain. De La Pole was Geoffrey Chaucer’s granddaughter and a significant and well-connected patron of the Arts. Whereas her pious effigy is carried up to Heaven by angels, the figure beneath is shown in a state of desiccation. Her hair runs free and her limbs are wizened. Gone is her wimple and coronet — now she appears half-dressed in a shroud, her feet bare and bony. Mortality is real, it seems to say, but your spirit can live forever in Heaven.

Into the wood

The Carved Room, Grinling Gibbons, Petworth House, West Sussex

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The Carved Room was installed in the 1690s by the 6th Duke and Duchess of Somerset.

The highlight of any tour of Petworth House is the Carved Room by Grinling Gibbons. Not only does it house a studio copy of Holbein’s Henry VIII, but it is decorated in gravity-defying swags and musical still lifes carved from limewood. Horace Walpole described it as ‘the most superb monument of his skill’. It was installed in the 1690s by the 6th Duke and Duchess of Somerset and was originally half the size. A century later, the space was expanded by the 3rd Earl of Egremont to create a grand dining room. He painted the panelling white behind the limewood carvings and commissioned four Turner landscapes of his parkland and investment projects (Brighton’s Chain Pier and the Chichester canal) to hang under the portraits.

Sailing the seven seas

The James Cook collection, Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford

Captain James Cook — who has a collection in Oxford's Pitt Rivers Museum.

You must work hard to find the 18th-century James Cook collection in the Pitt Rivers Museum. First, you need to locate the museum itself through an archway at the back of the central hall in the Oxford University Museum of Natural History. Then, you must navigate a maze of glass cases to access the first-floor balcony. There, in a single case, the cultural artefacts gathered by Capt James Cook on his three world voyages are clustered together. There are sculptures taken from the prows of canoes, imposing ceremonial robes, bundles of bark cloth and green nephrite pendants with circular shell eyes. Although there may have been little sense of the historical and contextual importance of such artefacts from Polynesia, New Zealand and Australia when they were first exhibited, they nevertheless inspired 20th-century Modernist sculptors in Britain, including Henry Moore and Henri Gaudier-Brzeska.

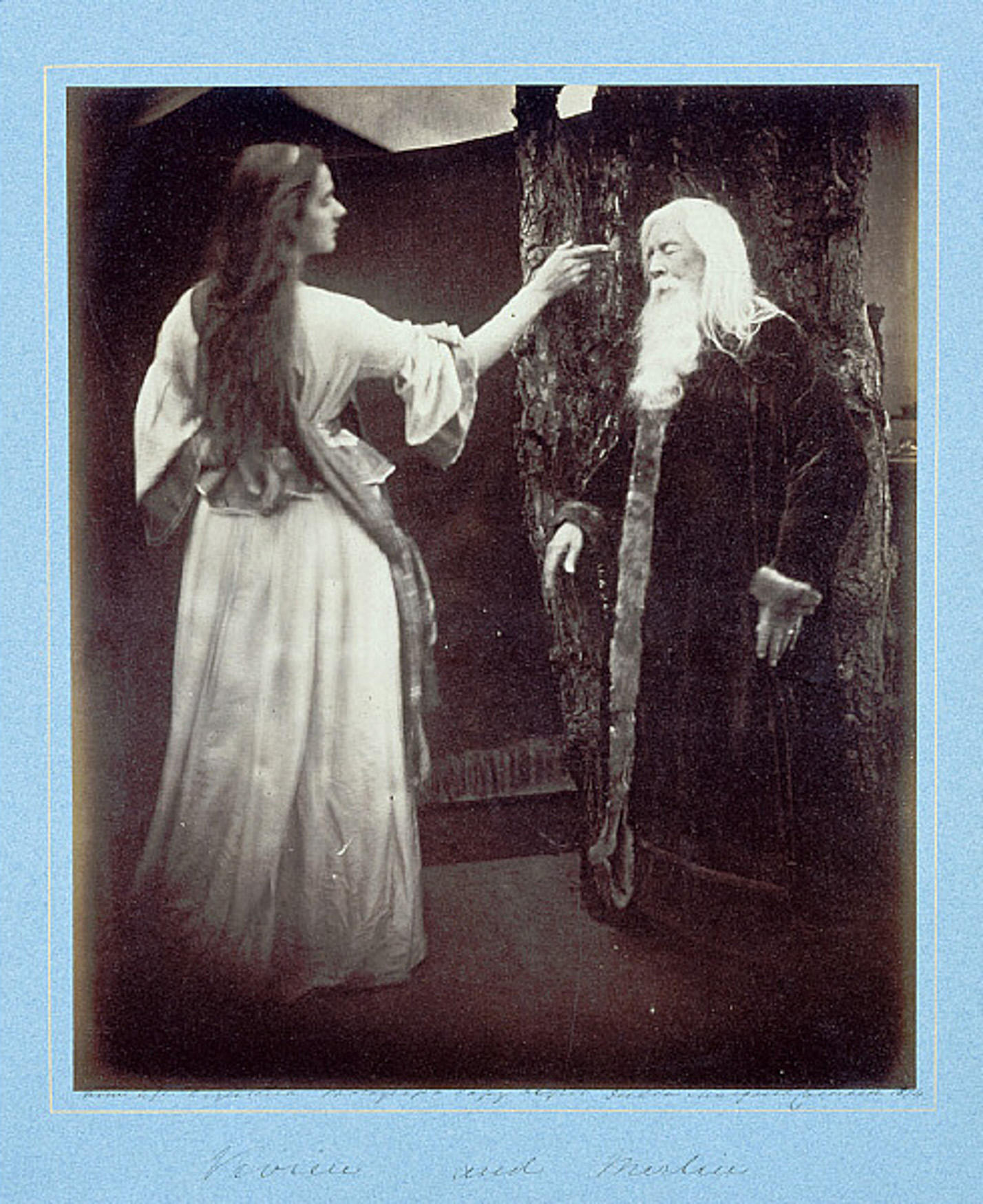

Pretty as a picture

Dimbola Museum and Galleries, Freshwater Bay, Isle of Wight

'Vivien and Merlin' by Julia Margaret Cameron.

Julia Margaret Cameron was one of the first photographers to use the camera to make art. She experimented with composition and focal depth, staging literary and classical scenes with her friends and family as models. She also took nuanced portraits of the Freshwater Circle, the members of which frequented her house, Dimbola, in Freshwater Bay, Isle of Wight, including Alfred Lord Tennyson, Ellen Terry, G. F. Watts and William Holman Hunt. Cameron and her husband, Charles Hay, owned tea and coffee plantations in Dimbula, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), and named their house after the estate. Most of Cameron’s photographs were taken at Dimbola; today, her home is open to the public and visitors can see Cameron’s studio, housed in a former chicken shed.

Brick by brick

The Watts Chapel, Mary Watts, Compton, Surrey

The Watts Artists’ Village is a must see on a trip to Surrey.

You may first decide to visit the Watts Artists’ Village near Guildford, Surrey, to see the purpose-built gallery of G. F. Watts, a hugely successful Victorian painter. Or you may choose to walk around the family home, Limnerslease, where pulleys in Watts’s studio allowed vast canvases to be winched up and down. However, the highlight of your tour may well be the Watts Chapel, built by his wife, Mary, between 1895 and 1904. She had trained at the Slade School of Fine Art in London and was 32 years his junior — his success could have been intimidating, but she found her own furrow as an artist. She built the circular mortuary chapel collaboratively, teaching 70 local volunteers how to make terracotta bricks using intricate moulds. The exterior features complex Celtic ribbonwork (a nod to her Scottish ancestry), but the interior explodes in a riot of line and colour. Red, purple and green angels throng the walls, as pronounced vines (made from gilded gesso) snake towards the sky.

Bohemian Haunt

Charleston, West Firle, East Sussex

Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant rented Charleston in 1916.

The Bloomsbury Group’s Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant first rented Charleston, a farmhouse near Lewes, in 1916 to wait out the First World War, with Grant and his partner David Garnett working as farm hands to avoid enlisting. Friends and sometimes lovers, Bell and Grant also worked together, painting canvases as well as furniture, as part of Roger Fry’s Omega Workshops. After 1918, they largely lived in London, returning to Charleston for summers of free and experimental loving, living and thinking, but moved there full time when the Second World War broke out. Their take on French Modernism is fused with an ongoing exploration of pattern and flatness, seen in the paintings that adorn the house’s doors, pelmets, tabletops, tiles, plates and lampshades, as well as walls.

Memories of war

Stanley Spencer murals, Sandham Memorial Chapel, Burghclere, Hampshire

The Sandham Memorial Chapel on the outskirts of Burghclere.

Stanley Spencer is most often associated with Cookham, the Berkshire village where he spent his childhood and much of his career. In 1927, however, he embarked on a series of paintings for the Sandham Memorial Chapel on the outskirts of Burghclere, a project that would occupy him for five years. This private chapel was commissioned by John and Mary Behrend and dedicated to Mary’s brother Harry, who had died of an illness contracted during the First World War. Both Harry and Spencer had served in Thessaloniki, Greece. The latter had worked as a medical orderly before enlisting in the infantry and he drew on his experiences of service for this task. His paintings fill the entire chapel, culminating in a vast depiction of dead soldiers rising from graves to hand white crosses to Christ on the East Wall. Others feature scenes of war from behind the front line — wounded soldiers arriving at hospitals, patients being cleaned, laundry washed and tea urns filled.

Home is where the art is

Barbara Hepworth Museum and Sculpture Garden, St Ives, Cornwall

Barbara Hepworth's sculpture garden is a popular attraction in Cornwall.

Barbara Hepworth had been part of the Hampstead Modernists during the 1930s, but, when war broke out, she moved with her husband, Ben Nicholson, to Carbis Bay in Cornwall. She bought Trewyn studio in nearby St Ives in 1949 and, following her separation from Nicholson, lived and worked there until her death in 1975. Her house, studio and garden were opened to the public as a museum in 1976. Today, you can follow her life as a sculptor in the displays in her former bedroom and kitchen, then enter her walled garden, where her plaster and stone studios remain untouched, her overalls still hanging on the door. She curated her garden to showcase her organic works, which carry within them the rhythms of the sea and the landscape she worked in. Her museum is now part of Tate and there are plans to turn her studio in the old dance hall next door into further exhibition space for St Ives’s most famous artist.

Follow the links for our other instalments of this series which look at London, the East of England, Scotland, the North of England, Wales, the Midlands and Ireland.

This feature originally appeared in the December 31, 2025, issue of Country Life. Click here for more information on how to subscribe.

Charlotte Mullins is an art critic, writer and broadcaster. Her latest book, The Art Isles: A 15,000 year story of art in the British Isles, was published by Yale University Press in October 2025.