'Uncut Gems' and the mystery of the most significant collection of Tudor and Stuart jewels ever found in London

As the London Museum prepares to unveil the Cheapside Hoard in new premises on Smithfield, Will Hosie speaks to historian Victoria Shepherd about the story behind these precious jewels.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In Josh Safdie’s 2019 neo-noir thriller, Uncut Gems, Adam Sandler plays a jeweller in New York’s Diamond District named Howard Ratner. His declining fortunes seem to turn suddenly after he receives an Ethiopian black opal matrix from an associate. The stone doesn’t look much — Esquire once called it ‘a tarry, shimmering button’ — yet, as he gazes into it, eyes wide and grin wider still, he realises, as do we, that this is an object of truly sensational value.

Black opals, which are more delicate than diamonds, form when water and silicone dioxide evaporate from the cracks of sandstone. The darker the body tone, the more desirable the opal. They are notoriously hard to find, which explains why Howard is reluctant to lend it to basketball champion Kevin Garnett, who conveniently finds himself in the store right as the opal gets delivered.

The sportsman believes it to be his lucky charm, Heaven-sent. After much smooth-talking, Sandler's character hands it over to him on the condition that it’s for one night only. Kevin has a game on and he’s feeling himself; inspired by his blind self-belief, Howard places a bet on his team winning. The gamble pays off. Howard rubs his hands together. He’s made a killing and the opal will be his again tomorrow.

Or so he thinks. Kevin and his entourage, naturally, have other plans, kickstarting a chain of events that ends in chaos and tragedy. Yet the story of how the London Museum (formerly Museum of London) came into the possession of the Cheapside Hoard is stranger and more dramatic, still.

In the 16th and 17th centuries, the salamander was believed to be able to withstand fire, making it a symbol of resurrection. This amphibian — part of the Cheapside Hoard — is set with Colombian emeralds and Indian diamonds.

The Hoard is the most significant collection of Tudor and Stuart jewels ever found, a veritable anthology of treasures acquired via different trade routes. Its story, to this day, remains one of London’s most beguiling. A treasure chest containing the jewels was discovered on June 18, 1912, at a time when a growing urban population was transforming the cityscape. Old homes were being razed to clear the way for mansion flats and, in order to build up, developers had to build down, laying more solid foundations deep into the ground.

Workers were expected to excavate several tons of London clay per day, which often meant having to dig right down to Roman level. As each layer of history was diligently removed, new artefacts would reveal themselves to labourers: a portal to an era in which various goods had been buried or left behind. No era fascinated the Edwardians more than the Elizabethan age — so you can imagine the delight of the two workmen who came across the Cheapside Hoard as they dug out the new foundations for Wakefield House that summer.

Author and historian Victoria Shepherd has a new theory about when, and why, the jewels were buried in Cheapside.

Wakefield House was built as a headquarters of the industrial tycoon Charles Cheers Wakefield and rose where the Worshipful Company of Goldsmiths once did. This was the professional association of jewellers who had previously occupied the area and whose legacy is still felt today in the name of nearby arteries (think Goldsmith Street). It is here that I meet Victoria Shepherd, a historian and the author of Stony Jack and the Lost Jewels of Cheapside (Oneworld, £20). Ahead of the extant jewels’ much anticipated unveiling at the newly rehomed London Museum later this year, she’s come up with a new theory about when, and why, these might have been buried here.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The ‘Stony Jack’ in her title refers to George Fabian Lawrence, an antiquarian dealer and legendary figure of the age. The labourers who uncovered the Cheapside Hoard could easily have made off with the bounty, Victoria claims; instead, they took it to Stony Jack, who operated out of a pawn shop in Wandsworth. The story is positively Uncut Gems-esque: ‘They dropped concrete footballs, lumps of clay, onto Stony Jack’s desk’, says one account — from whence poured countless jewels made of diamonds, rubies and sapphires. In total, the Cheapside Hoard consisted of nearly 500 pieces, including rings, brooches, necklaces, a salt cellar and a watch encased in a Colombian emerald the size of a small apple.

An early-16th-century gilt-brass verge watch made by Gaultier Ferlite of Geneva, Switzerland.

Over the years, Stony Jack had forged strong relationships with London’s builders, who trusted both his expertise and character when it came to evaluating the worth of their finds. He was known to pay people cash down, no questions asked, and typically sold the valuable works on to museums. His primary options for the Cheapside Hoard were the London Museum and the Guildhall; he favoured the first, in its infancy at the time, having been established in 1911. Soon enough, the museum named Stony Jack its Inspector of Excavations.

The uncovering and eventual traffic of the Hoard in 1912 inspired all sorts of conspiracy theories. Why, indeed, had it been buried in the first place? Why had no one come to retrieve it before then? It has long been believed that the Interregnum was to blame: the political and religious upheaval of the 17th century meant it was perfectly conceivable that a goldsmith might have had to flee town and leave his wealth behind. Victoria’s tale of the Cheapside Hoard, published last June, builds on this theory.

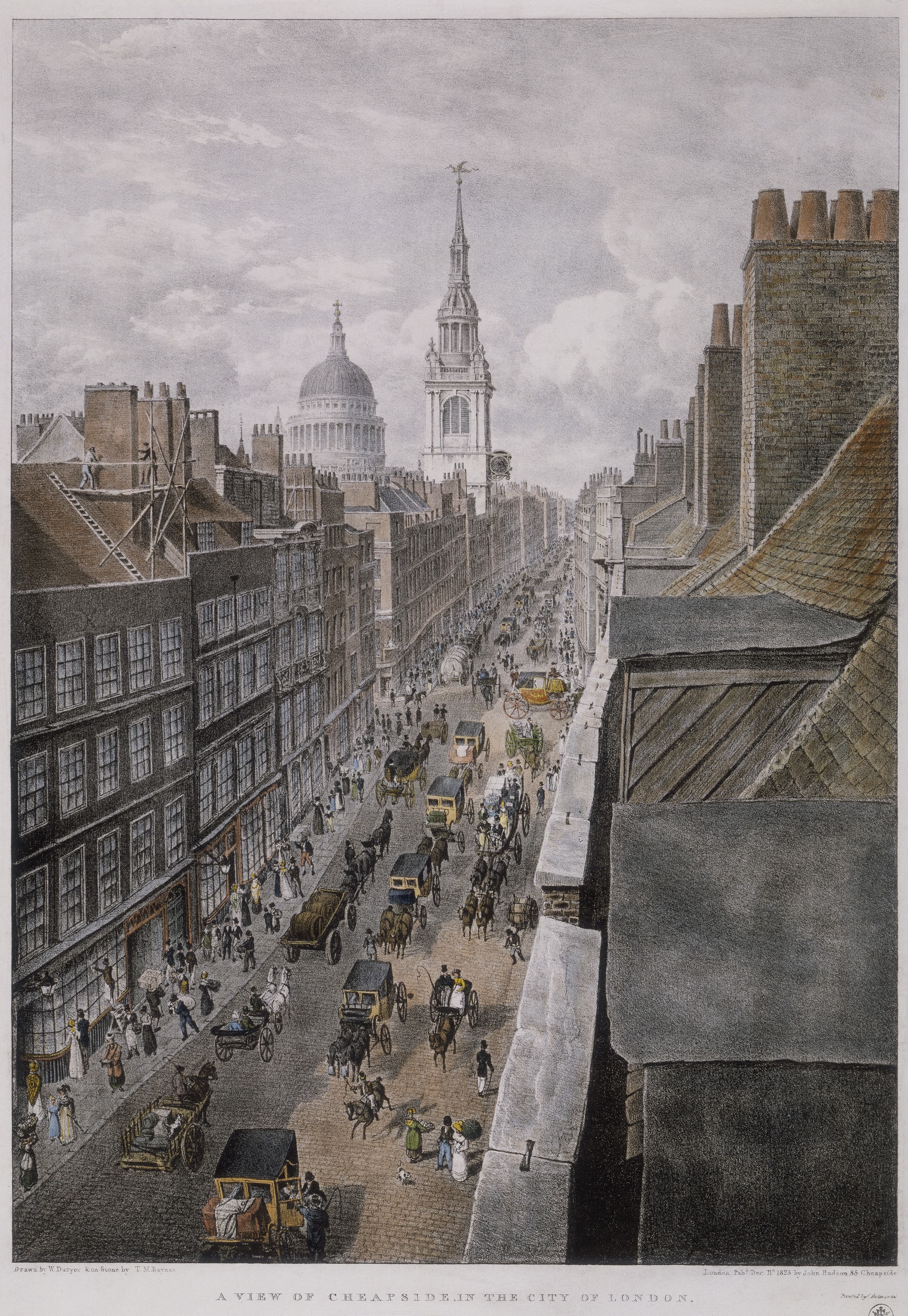

The hustle and bustle of an 1820s Cheapside unaware of hidden treasures in its midst.

When studying an archival lease document for William Taylor, who took the premises on the site near Goldsmiths Row in 1654, she noticed a passing reference to one Francis Simpson, identified as the property’s previous leaseholder and a jeweller who supplied fashionable pieces to the Court, as well as more modest ones to the mercantile class. He had refused to renew his lease in 1641, on the basis that the structural improvements he’d made to the building as leaseholder were enough to offset the costs. The Goldsmiths’ Company did not accept this explanation and Simpson ended up having to pay rent, on top of fines he had accrued when trying to cut corners.

Then came the Civil War: Simpson, who was a staunch Royalist, fled London for Oxford, where he became Charles I’s royal jeweller. Throughout this time, he refused to pay rent on the shop in Cheapside because that would have meant lining the coffers of a now Republican parliament.

After the Sequestration Committee was set up, the bailiffs came to his premises to requisition the property. His staff of artisans, who had been manning the shop in his absence, promptly hid the jewels ‘somewhere out of the way, at the back of the building, butting up to the boundary with the neighbouring property in a sturdy, brick-lined cellar,’ Victoria writes.

When Oxford surrendered to the Parliamentarians, Simpson was sent to prison. Yet he came back to London after the Restoration had taken place, ready to reclaim his shop and its hidden treasures and wrestle it off whoever occupied the premises at present. Ultimately, however, Simpson was hampered by debt and the Goldsmiths’ Company did not permit him to take out a lease on its watch again.

He returned to his role as royal jeweller and was in town when the Great Fire of 1666 engulfed the City. Cheapside went up in flames and, according to Victoria, Simpson would have believed the Hoard was lost forever. He didn’t realise, however, exactly how well, deeply and safely it had been hidden. No one would, in fact, until 246 years later.

Simpson, believes Victoria, was thus the mystery architect of the Cheapside Hoard, carefully acquiring and remodelling the collection over several decades, according to the fashion of the age. Why he didn’t take the jewels with him to Oxford might raise a few eyebrows, but Ms Shepherd has a theory for this, too. ‘He was, at the time, making diamond-heavy decorations to the highest possible specification for the Royal Court and the pieces and loose stones in the Hoard were, with a few exceptions, not sufficiently grandiose for his work in progress.’

The hero of her book, however, is Stony Jack, of whom she produces one of the most complete portraits to date. He was ‘a clairvoyant’, she argues: someone who could slip seamlessly between the past and the present, peer into a gemstone and understand its provenance in the manner of a mystic (or, indeed, of Kevin Garnett).

A gold wire pendant decorated with 12 alternating bands of enamel and pearls, with a six-armed spray of articulated gold wire set with pearls. Some of the pearls are missing.

We know today that the collection drew from Burma, Colombia and the Persian Gulf, the fruit of budding trade routes to the New World and the Far East. Remarkably, ‘the less ostentatious jewels are some of the most interesting,’ as Victoria notes, ‘because many of them depict myths and symbols loaded with superstition’.

The London Museum was the primary beneficiary of Stony Jack’s antiques trade and holds the single largest slice of the Cheapside Hoard since it was discovered. Some of it was still on display when the museum closed its previous site in 2022, but much of it was on loan or stored underground in the vaults. This year, the full collection will go on show for the first time after the museum reopens on Smithfield, increasing its surface area from roughly 4¼ to 6¾ acres. Victoria, for one, is thrilled: if Edwardian England was in thrall to the tale of the Hoard, it’s one of those London legends to which time has been unkind — until now. Seeing it in all its glory after uncovering the true story, it seems as if this tale might have a far happier ending than that of Uncut Gems.

The London Museum, Smithfield, reopens in late 2026. Visit their website for more information.

This feature originally appeared in the February 4, 2026, issue of Country Life. Click here for more information on how to subscribe

Will Hosie is Country Life's Lifestyle Editor and a contributor to A Rabbit's Foot and Semaine. He also edits the Substack @gauchemagazine. He not so secretly thinks Stanely Tucci should've won an Oscar for his role in The Devil Wears Prada.