The rugby shirt is a bona fide sartorial superstar

Once the reserve of mud-caked public schoolboys, the rugby shirt is now embraced by outfitters across the globe.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The rugby shirt: a perpetual, indefatigable superstar. Conceived for the clatter and oomska of the pitch, the past five decades have seen it reconfigured as a staple of au courant wardrobes across the world.

Its genesis came in 1823 at Rugby School in Warwickshire, when William Webb Ellis apocryphally picked up a football and charged towards the opposition. Back then, an impractical uniform of white, long-tailed shirts was worn — being readily available and easy to boil wash — with coloured caps to differentiate between teams and avoid boys indiscriminately trampling each other into the mud.

In 1846, shortly after the sport’s rules were formalised, it was decreed that the caps must go and that one team must wear colourful garb in their place. Woollen jumpers with oversized collars — also folly, given the sport’s sweaty, rain-flecked demands — and white trousers became standard. During the 1870s, sense was finally seen and the thick, tightly stitched cotton silhouette we know today was introduced. Robust and resistant to the ferocity of the pitch, patterned in school-coloured ‘hoops’ and replete with a smaller, rigid collar (less prone to being yanked in the scrum) and rubber buttons (kinder on the faces of opponents, hidden behind a cotton fold), a paragon was born.

For decades, the rugby shirt remained the preserve of the quad and cloisters; worn off-field as a signifier of schooling. That was, however, until the release of Lindsay Anderson’s 1963 kitchen-sink classic This Sporting Life, a rough-and-tumble tale of a northern rugby league player’s on- and off-field travails, which popularised the shirt in the public imagination of Britain and within the varsity milieu of the USA (thanks in no small part to the battered rakishness of Richard Harris’s Frank Machin).

Taylor Swift shakes it off in a long-line shirt in 2023.

Across the globe, another touchstone arrived in 1965 with the publication of Take Ivy —a hallowed Japanese style tome and pacific primer on collegiate American fashions by photographer Teruyoshi Hayashida, named after a Dave Brubeck jazz standard. Shot on Ivy League campuses, it kickstarted the trend for preppy threads among the hip youth of Tokyo’s Shinjuku City and Ginza — not least the rugby shirt, of which it included a popping red example. The stage was set: the rugby shirt’s transition to the casual wardrobes of the wider populace was in motion.

The shirt’s first real break from its academic confines occurred in a location almost as unforgiving as the pitch. In the winter of 1970, American climber Yvon Chouinard was mountaineering in Scotland. Spotting a clued-up British climber wearing a rugby shirt, he figured that the top’s sturdy, 14oz cotton construction would be perfect for scrambling across rock faces and its stiff collar ideal at stopping his heavy slings of climbing hardware from chafing. Chouinard brought home a vivid azure shirt with yellow and red hooping. His Californian climbing compatriots loved it, so he imported more and labelled them under his nascent outdoors brand: the now totemically influential Patagonia. ‘Rugby is a skin-shredding game; for decency’s sake, the clothes are designed to outlast the flesh,’ claimed a 1975 catalogue for Chouinard’s bricks-and-mortar store, Great Pacific Iron Works. ‘A number of years ago we stumbled onto the obvious parallels.’

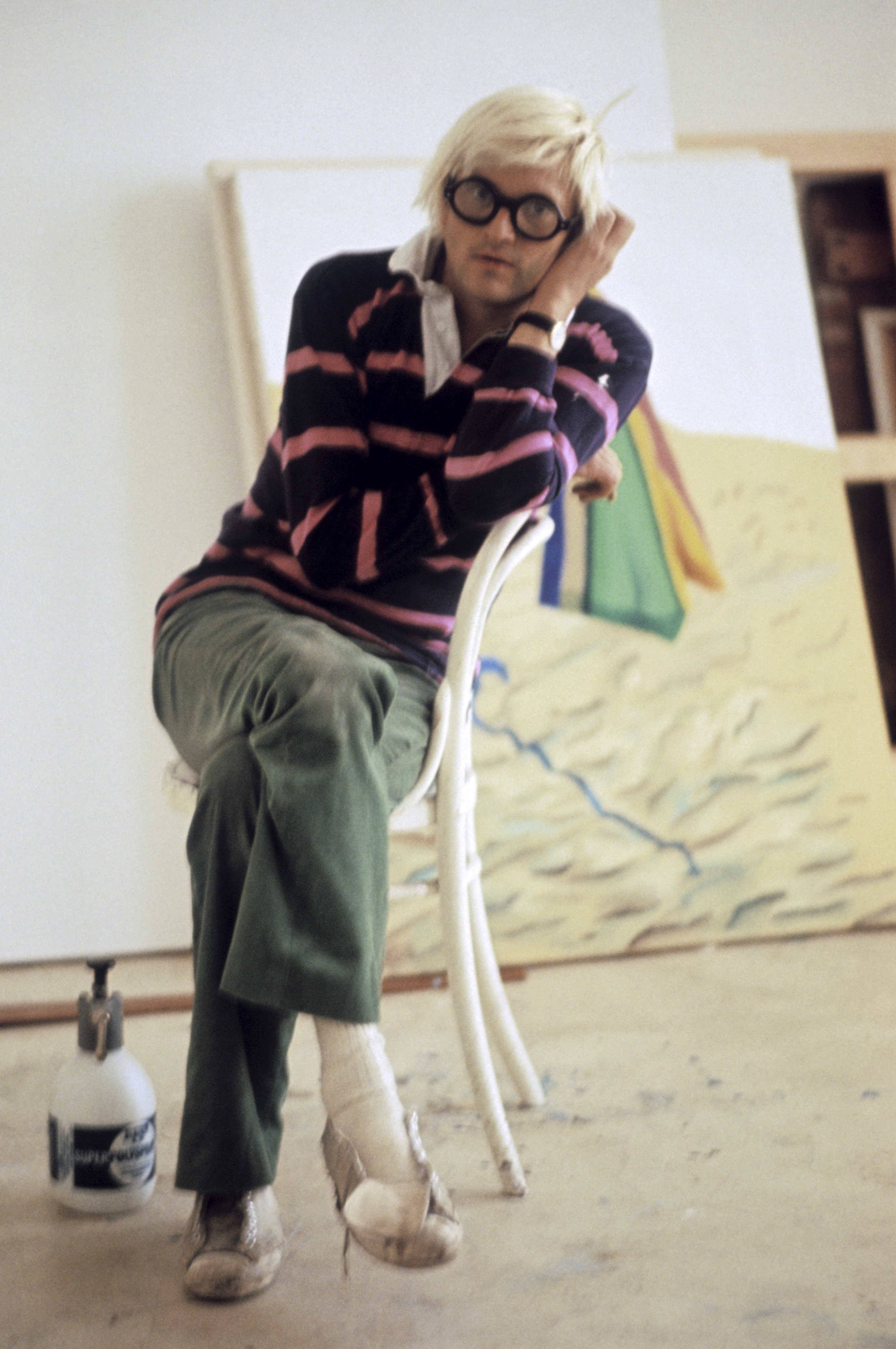

David Hockney updates the artist’s smock in 1971.

The years since have seen the shirt proliferate across demographics. Its bombproof construction and timeless aesthetic transcend fashion’s transient whims and it is currently enjoying the purplest patch of its long history. It remains ubiquitous across the inventories of preppy stalwarts, including Ralph Lauren, and, in London, the wave has been crested by vintage-chic outfitters such as William Crabtree & Sons, Black & Blue 1871 (with neat facsimiles of the Patagonia shirts, plus throwback public-school designs) and, especially, Savile Row’s Drake’s (founded in 1977), which has embraced slimmer cuts, shrunken collars and painterly colourways.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

‘We wanted something that felt casual yet substantial — a garment with character, rooted in heritage, but easy to wear,’ explains brand and creative manager Junyin Gibson. ‘At Drake’s, we like pieces that have a bit of soul; that stand the test of time, and can be both slightly scruffy and deeply elegant. The rugby shirt embodies that balance perfectly.’

Although the game itself might have long capitulated to tackle-abating, skin-tight technical fabrics, the 21st century’s sartorial innovators have kept their own versions of rugby’s quintessential aesthetic in rugged good health.

Tom Howells is a London-based journalist and editor, who has written for the Financial Times, Vogue, Waitrose Food, The Quietus, The Fence, World of Interiors, Wallpaper*, London Design Festival and more. He’s happiest when drifting the woodland barrows of the Isle of Wight and once got locked in Carisbrooke Castle. 'Ancient Britain for Modern Folk' is his third book.